A faction of Americans have co-opted and weaponized “patriotism” to lord bigotry over immigrants—especially those this administration has separated from their families.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

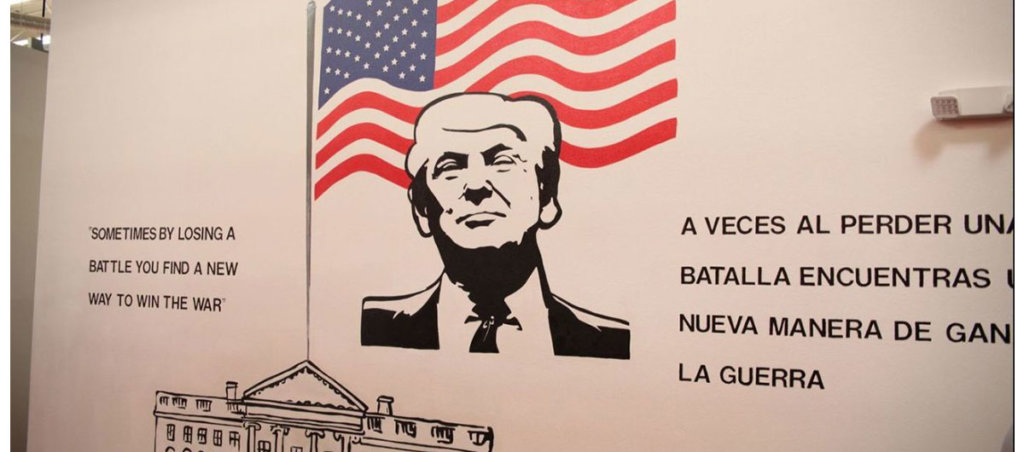

In June, MSNBC correspondent Jacob Soboroff tweeted some of the first pictures from within border detention center, Casa Padre in Brownsville, Texas. Among the images of kids contained in dog-like kennels, was a mural of Trump’s face over an American flag with a quote from The Art of the Deal, written in English and Spanish, that read, “Sometimes by losing a battle you find a new way to win the war.”

For families, many fleeing violence in their home countries, the trauma of separation was abrupt and unexpected. Parents described having no opportunity to even say good-bye. Some said they were lied to, told that their kids were being taken to shower but then never returned. Some said they were asked to help buckle their crying children into cars that were leaving without them.

Trump murals are painted on the children’s detention centers, there to offer not a welcome but a warning: In Trump’s America, immigration is treated as an invasion, an act of aggression. While this deliberate psychological abuse isn’t relegated to immigration detention centers (Trump supporters have been utilizing “patriotic” symbols, like MAGA hats and American flags to taunt and intimidate marginalized groups since the early days of his campaign), the impact is the greatest on vulnerable children who’ve been separated from their parents.

As we witnessed from ProPublica’s excruciating eight-minute audio recording of some recently separated children, who were crying and pleading for their parents, the kids were distraught and confused. For these children, a mural, like the one at the detention center, acts as a reminder of who is responsible for their anguish and suffering—they’ve been kidnapped by the U.S. government—and whom they must now depend on for survival.

Dystopian stories exploit this dynamic well. The relationship between the handmaids and Aunt Lydia in The Handmaid’s Tale, for example, demonstrates frighteningly well how an overlord psychotically straddles the roles of caregiver and cruel authoritarian. The handmaids fear Lydia and also depend on her; she can end them and also provide comfort. Though she creates and enforces the rules and consequences, she soothes the handmaids by telling them that if they would just be good girls nothing bad would happen to them.

Which is what Attorney General Jeff Sessions told parents, that if they didn’t want their kids taken, just don’t cross the border with them. Or the way that Trump acted a “hero” in revoking his own policy, as though he weren’t the very reason these children were being tormented in the first place. It doesn’t matter that seeking asylum isn’t illegal, just like it doesn’t matter how “good” a handmaid tries to be. There is no winning in psychological warfare.

After kids were shuffled all over the country, from border detention facilities and into foster placement, an NBC News report profiled one Michigan foster parent, who had been taking in unaccompanied children since 2016. Before Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy, these children were mostly adolescents, who had crossed the border, alone. Now children as young as 5 years old were entering her care, and their trauma was severe—some cried constantly, others went mute, all were confused. A striking picture in the story shows the foster children’s bedroom in the family’s home. On the nightstand between the two beds? An action figure, holding a mini American flag.

For adolescents who cross the border without a parent or guardian, maybe that kind of decoration wouldn’t elicit so much as a shrug. But for kids who were literally ripped from their parents’ arms, held in cages where American flags and presidential murals plastered the walls, and who were then shipped across the country to strangers’ homes with little understanding of what was happening, “insensitive” would be an understatement. The context is different and intended or not, so is the message. To traumatized, separated children, the flag represents their imprisonment. Meanwhile, in America, the flag has become a symbol of intolerance; a weapon deployed to convey entitlement.

Political symbols derive their meanings from their impact. When flags are flown at certain events—in opposition to the values those events represent—those flags become symbols of that opposition. When they are flown symbolically at rallies alongside other symbols of hate and messages of supremacy, those flags becomes synonymous with that ideology. And those symbolic meanings don’t get left behind at rallies or isolated events. They are ingested as the intimidation and hate that they are intended to convey.

In the ten days following the 2016 election, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported that there had been nearly 900 hate incidents reported to their #ReportHate page and in media accounts. In 2016 there were 6,121 hate crimes reported to the FBI (up from 5,818 in 2015) and, according to information compiled by the SPLC, hate groups rose for a second year in a row in 2016.

Since the election, not only have white nationalist rallies been on the rise, but their presence at Black Lives Matter events, women’s marches, and immigration rallies has increased, too. And those counter groups nearly always don at least one American flag, as if to say, ”Your values of inclusion, peace, and justice are not American values; ours of white supremacy are.” Extremists often pair the American flag with confederate flags, Nazi flags, Thin Blue Line flags, and “Don’t tread on me” flags. The Gadsen flag, as the yellow snake flag is known, was originally designed in the 18th century to represent the revolution and rebellious independence from Britain. But, as Rob Walker points out in his piece about the Gadsen flag for The New Yorker, “no symbolic meaning is locked in time.” Today, the Gadsen flag has become a symbol attached to the tea party and Second Amendment movements.

Back in child detention facilities, flags and patriotic murals hang amid deplorable conditions—inmates have described abuse, hunger, and being forcibly given psychotropic medications without their parents’ consent. Some kids became ill, none—per policy—received comfort, and one child even died shortly after being released from a Texas detention center. The patriotic symbols in these facilities are a consistent weapon used against vulnerable children, who are enduring horrific torture at the hands of our government.

Historically, political flags have been routinely morphed into tools of oppressive intimidation and worse. In South Africa, for instance, the Apartheid flag came to represent white minority rule. As the BBC reports, the flag “was based on the Dutch Prince’s flag, and included smaller flags of the Orange Free State, South African Republic and the British Union Jack—all reminders of the country’s colonial past.”

That flag was later replaced by the current South African flag. While those who fly the Apartheid-era flag today claim it is nothing more than embracing “heritage” (sound familiar?), the impact of flaunting that brutal history for Black South Africans can be painful. Dylann Roof, the white supremacist convicted of the Charleston church shooting, wore an Apartheid flag patch on his jacket.

In the U.S., the Confederate flag is the symbol most associated with racist intimidation. And while proponents of displaying that symbol also tout “heritage” as their rationale, it’s important to point out that most people proud of their ancestry or identity don’t usually install giant flagpoles on their vehicles to wave full-size flags honoring that identity. That tactic is unique to people displaying flags that represent division, supremacy, and nationalism. The flags are big, they’re portable, and they’re intimidating. And that’s entirely the point.

As we know from social justice movements, impact is greater than intent. When a patriotic symbol, such as a flag, has been used as an intimidation tool by extremists, it’s hard to represent that same symbol and then hope another message shines through. The swastika was used for 5,000 years before it was coopted by Nazi Germany as a symbol of hate. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the word swastika comes from the Sanskrit and means “good fortune” or “well-being,” and the symbol was originally one of good luck and auspiciousness. It is no longer possible, though, to reclaim that original meaning when so many millions suffered and died under it. Germany understands this, and the detrimental impact of displaying the swastika, and the country has strict laws banning them.

It is difficult to say whether the American flag has or will cross that kind of threshold, but it’s important to consider what effects political symbols have on oppressed people. The current administration has locked kids in cages and lined the camps’ walls with presidential faces and flags, all while our sitting president simultaneously condemns those who don’t stand in salute. Like it or not, it’s important to remember that we’re sitting in a time where the American flag invokes feelings of terror for an increasing number of people. And it’s the most vulnerable among us that experiences that terror the worst.