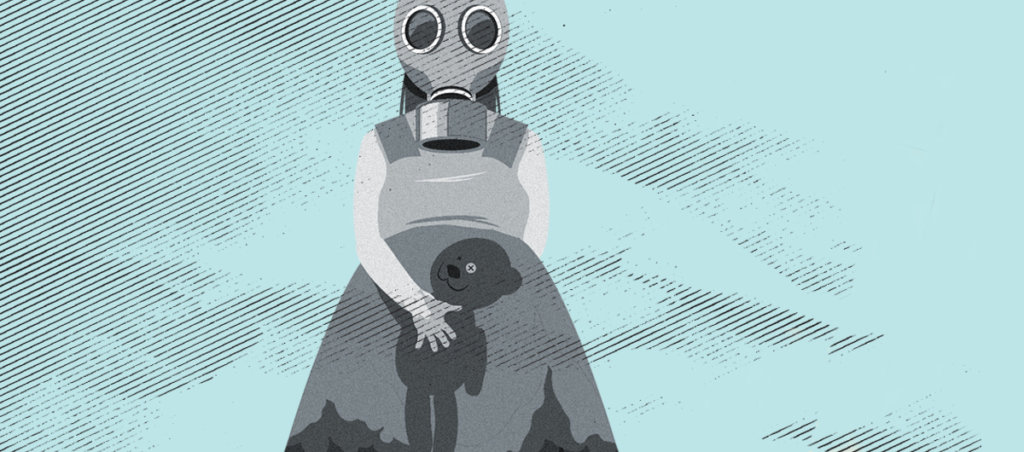

Exposure to the chemical chlorpyrifos, which is in flea bombs, may have caused birth defects in the writer’s children. Now she’s fighting to uncover the truth to protect other families.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

It’s 1989. I’m 26, 19 weeks pregnant, and I really need to pee. The technician calls my name and I follow her to the examining room where I undress and slip under the cold white sheet on the examining table. After some discussion about morning sickness, she applies gel to the wand and places it on my small baby mound. She gently presses the wand over my full bladder. I feel a slight release of warm urine between my legs. She presses the wand a little harder. Then takes another pass around my mound before returning it to its cradle and telling me, “Wait here, I’ll be right back.”

“Is everything okay?” I ask.

“The doctor will explain.”

I’m frightened and alone, and no longer worrying about needing to pee. I’m only thinking: Is my baby alright?

The answer is no. What the technician saw and what the doctor now explains is that my baby is developing with numerous birth defects, namely spina bifida—a neural tube defect in the upper-lumbar region where the baby’s spinal cord hasn’t closed—and anencephaly, a serious malformation of the brain.

Long hours turn into endless days. My husband, Steve, and I meet with a geneticist who asks about our family history—most of which I can’t answer because I’m adopted—and lays out the baby’s dire prognosis and our options for addressing it. We ask what caused the baby’s neural tube and brain defects. The geneticist offers no clear answer, only reassurances that the cause of the abnormalities is likely environmental, meaning our future pregnancies probably aren’t at risk.

I was far from reassured by these words. All I hear is: You did something wrong to cause this.

She tells us the baby has a 50/50 chance of surviving to full-term, and if the baby does survive, he or she will be paraplegic, or even quadriplegic. The baby will also be severely cognitively impaired, require a brain shunt, and will likely die within six to nine months of birth.

That’s option A.

We ask about terminating the pregnancy. The doctor looks down at her notes then replies, “It’s late, but you still have that option.” Steve and I exchange clueless looks. “Go home and sleep on it,” she says, as if sleeping is an option.

Faced with bad and worse options, we choose worse—or is it bad? At 21 weeks, the doctors sedate me then proceed to disassemble the growing child inside my womb before sucking the remains out of me with a vacuum. I mention these details not because I am opposed to abortion. I’m not. But because I asked the doctor what the procedure involved and I continue to live with this visual and the trauma of ending a life. Abortion is not always a simple case of wanting or not wanting a child—I desperately want the one I’m carrying. There are other, complex layers that often get overlooked in the contentious debate over abortion. But that’s a whole other story.

After the procedure, I ask my obstetrician the baby’s sex—something the ultrasound technician hadn’t looked for once she’d found the abnormalities. “A girl,” my obstetrician, Dr. Hansen, tells me.

Steve and I leave the hospital and head for Windansea Beach, where we hold hands, and cry. We decide to give our daughter a name: Caitlyn.

After the abortion, I fall into a depressive stupor and spend days racking my brain trying to figure out what I did to cause my baby’s defects. Was it because I kept forgetting to take my prenatal vitamins? Could it have been the two beers I drank at the Indigo Girls concert, or the flea bombs we used in our condo, both occurring before I learned I was pregnant? Perhaps it had been my twice-a-week tennis lessons?

It will be 28 years before I happen upon what I think is the answer. In March 2017, I’m driving down Highway 1 in Southern California listening to NPR’s All Things Considered when I hear a story about how Scott Pruitt, Trump’s former administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, is lifting a ban on the pesticide chlorpyrifos, which numerous studies have linked to neural tube defects and brain malformations. “Until the late 1990s,” the reporter says, “chlorpyrifos was the active ingredient in household flea bombs.” I sit bolt upright.

What’s Invisible, Smells Like a Skunk, and Kills Fleas?

Chlorpyrifos is an organophosphorus insecticide that was used in the home to control cockroaches, fleas, and termites, and was used as an active ingredient in some pet flea and tick collars. It belongs to a class of chemicals developed as a nerve gas by Nazi Germany. Human and animal studies show that it causes structural damage to the brain, diminished IQ, and neurobehavioral deficits in children. It has also been linked to heart disease, lung cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and the lowering of sperm counts.

The Dow Chemical Company first started production of chlorpyrifos in 1965, branded under two names: Dursban and Lorsban. In 1989, virtually all store-bought flea bombs contained chlorpyrifos. When the chemical is released from a container to treat a large area in the home—the manner in which we used it—it volatilizes and then it settles back on the surface of any object in the vicinity, e.g., a child’s toy or a pregnant mother’s food. I was likely exposed to chlorpyrifos by breathing, eating, and drinking the substance and by skin contact from touching surfaces in my home after we set off the flea bombs, and from touching the flea collars of the cats.

Dow’s Deception

Sometime in the late ’80s—around the time I was pregnant—reports began to surface at Dow Chemical that the metabolic breakdown of chlorpyrifos caused central nervous system abnormalities (hydrocephalus and dilated brain ventricles), and other abnormalities (cleft palate, skull and vertebral abnormalities) in fetuses. However, Dow didn’t forward these findings to the EPA until 1994, with reporting delays of as long as seven years from when the company first learned of the effects of in-utero exposure. Dr. Janette Sherman uncovered Dow’s reports via a Freedom of Information (FOIA) request from the EPA, and Dow was eventually fined for withholding 249 reports stating that there were cases of poisoning by chlorpyrifos that they failed to forward to the EPA.

By the late 1990s, both the EPA and the FDA set tolerance levels for chlorpyrifos. Informed by Dr. Sherman’s case studies and a preponderance of other scientific evidence, the EPA finally banned the indoor use of the pesticide in 2001. However, the agricultural use of chlorpyrifos was still permitted, despite evidence showing that the chemical sickened farmworkers who applied it, and contaminated drinking water supplies in farming communities.

Even though there is a household ban in effect, we can still be exposed to chlorpyrifos if it has recently been applied to the ground around the foundation of our home or office to control termites. Children are especially sensitive to chlorpyrifos because their bodies break down pesticides differently. Children are also more likely to be exposed to pesticides when playing—they put their hands in their mouths more often than adults.

Despite U.S. regulations, Dow continues to sell the product in other countries, especially developing nations. In India, the claim is that chlorpyrifos has a record of proven safety for both humans and animals. However, a few years ago, the offices of the company in India were raided because it was discovered that Dow had bribed government officials to allow for the sale of their products in the country.

Research Leads to a Ban

It’s no easy feat to get a major chemical company to withdraw a pesticide from the market. According to Betty Mekdeci, director at the nonprofit Birth Defects Research for Children, the chemical and drug industries conduct reproductive studies in animals (usually rodents) during which the animal is exposed to a product for some time prior to pregnancy and throughout pregnancy. This creates enzyme induction which means that the animal’s body becomes accustomed to the drug. As a result, few or no teratogenic effects are found in the industry studies. Researchers, on the other hand, conduct teratogenic studies in which a pregnant animal is exposed to the drug or chemical at the critical time for organ and/or bone formation. Teratogenic studies are more effective at detecting birth defects especially if the test animal is also genetically predisposed to a particular type of defect. In short, chemical industry studies are purposefully designed to avoid certain developmental markers and therefore rarely produce reproductive effects. And once a product make it to market, the chemical industry routinely dismisses subsequent teratogenic studies that suggest deleterious effects of the product.

The groundbreaking research on chlorpyrifos by Columbia University’s Dr. Virginia Rauh has posed the most significant challenge to the pesticide. Rauh and her colleagues studied the brains of 20 children exposed to higher levels of chlorpyrifos in their mother’s blood (as measured by serum from the umbilical cord). The effects of chlorpyrifos could still be found in the brains of young children now approaching puberty. The study used magnetic imaging to reveal that those children exposed to chlorpyrifos in the womb had persistent changes in their brains throughout childhood.

In addition to structural changes in the developing human brain, the study also found that children who had chlorpyrifos in their blood had more neurobehavioral deficits—such as ADHD —than those who did not have it in their blood. Other effects that have been observed are instances of asthma and developmental delays.

In 2015, after a lengthy and expensive face-off between the chemical industry and farm interests on one side and public health and environmental advocates on the other, the EPA announced that it would ban the use of chlorpyrifos—noting that it was unable to find a safe level of exposure. It was set to take effect in the spring of 2017. Then Donald Trump was elected president.

What a $1 Million Donation Will Get You These Days

Less than three months into the Trump administration, 20 days after meeting with the CEO of Dow Chemical, and coinciding with a $1 million donation by Dow to President Trump’s inauguration, Trump’s then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt rejected the advice of his agency’s chemical safety experts and reversed the 2015 decision prohibiting the agricultural use of chlorpyrifos.

Pruitt took what is known as a “final agency action” on the question of the safety of chlorpyrifos—meaning it’ll be five years before the EPA is required to review the safety of the chemical, in 2022. Until then, farmworkers and their families would continue to be exposed. The American Academy of Pediatrics protested the decision. In a June 2017 letter to Pruitt, the association called the risk of chlorpyrifos to infant and children’s health and development “unambiguous” and urged Pruitt to listen to his own scientists and go forward with the proposed rule to end chlorpyrifos’ use.

Environmentalists and public health advocates filed a lawsuit late last year, and in August, a federal appeals court, siding with the advocates, ordered the EPA to bar within 60 days the agricultural use of the pesticide. As of today, it is unknown whether the EPA will appeal the decision to the Supreme Court. The $800 billion chemical industry will undoubtedly lobby the Trump administration to support such an appeal.

Premature Conclusion

It’s likely that my exposure to chlorpyrifos led to Caitlyn’s birth defects, but the damage and heartbreak didn’t end there. After losing another pregnancy to a blighted ovum in 1991, I get pregnant again. This time, I am assigned a “high-risk” obstetrician. My first ultrasound is reassuring: normal heartbeat. All other signs point toward a healthy fetus. I’d decide if I have a second good ultrasound, I’ll tell my family I’m expecting again.

The technician for my second ultrasound is Min, the same one who discovered Caitlyn’s troubles. Like a recurring nightmare, within minutes of the exam, I can tell by the look on her face that something isn’t right. As she had the last time, she excuses herself, returning minutes later with a radiologist. He takes over the controls, traversing and pressing my belly with the wand, before performing a vaginal ultrasound. He does not speak, and keeps the screen directed away from me. Finally, he places the wand in its cradle and directs his gaze at me. “I’m sorry,” he begins.

Somehow, I make it to the OB office across the quad from radiology. My doctor is on vacation so I’m seen by the OB covering for her. The OB repeats what the radiologist has already told me: There is no longer a detectable heartbeat and the amniotic sac is elongated, suggesting that I am in the midst of miscarrying. “Go home, drink a pitcher of margaritas and wait,” he tells me. “If you don’t miscarry by Monday, come back and we’ll perform another D&C.”

Because I’d forgotten my purse at the radiology clinic, I return to Min’s office, where she beckons me to follow her down the hallway, out of the receptionist’s earshot. I tell her what the OB said. She whispers, “If you don’t miscarry over the weekend, wait until Dr. Hansen returns before you do anything. I have a feeling—nothing based on medicine—that you won’t lose this baby.”

I don’t drink a pitcher of margaritas or miscarry over the weekend. Instead, I wait until Wednesday before returning to the office to hear Dr. Hansen’s assessment. Everyone in the office appears to know I am about to lose another baby. Dr. Hansen enters the exam room with an I’m-so-sorry expression on her face. Feigning optimism, she says, “Before we do anything, let’s have a quick listen.” She places the doppler on my underbelly. Crickets. She moves it upward to just below my rib cage and stops. I hear—or imagine—a faint sound, but nothing like a heartbeat. She turns the doppler 90 degrees, and there’s the sound again, only this time it’s louder, and rhythmic! We look at each other and both begin to cry. There is life inside me.

I wish I could tell you that the remaining months of my pregnancy was smooth sailing, but that’s just not how I roll. I spot heavily throughout the second trimester, so much that I decide to search for my birth parents to learn more about my medical history. I call my “uncle” Lester who was my parents’ adoption attorney for my brothers and me, explaining my circumstances. Fifteen minutes later, he calls me back with the notes from his interview with my birth mom, and reads them to me over the phone, including her maiden name. With the help of a private investigator friend, I track down Rose Sciuchetti, the woman who placed me for adoption because she couldn’t afford another child and refused the marriage proposal of her abusive boyfriend. Rose and I meet on my 29th birthday at her home in Elmhurst, Illinois. She told me everything she knows about her family’s medical history including her bout with ovarian cancer, and clinical depression, but is unaware of familial birth defects or pregnancy complications.

Stuart is my first child to be born. He arrives on April 17, 1992. But just as I was delivering my stubborn placenta, Stuart is taken from us for “further evaluation.” The following day, Stuart undergoes a six-hour operation to repair a tracheoesophageal fistula—his esophagus is connected to his trachea instead of his stomach, where it belongs. He recuperates for three weeks in NICU before I’m allowed to hold him again. He is diagnosed with VATER Syndrome, a satellite of birth defects including, in his case, the fistula, a wonky urethra, two hiatal hernias, a cockeyed aortic arch and a questionable kidney. As he matures, Stuart is considered a “failure-to-thrive” infant and reaches developmental milestones far behind schedule. At 13 months, we discover he has an anaphylactic allergy to peanuts; at 15 months, that he has asthma; and at 21 months, that he has severe reflux, which explains his colic and recurrent pneumonia. By the time Stuart is 10, he’s endured 19 surgical procedures, three of them major.

Stuart’s chronic health issues subside for four years, so we wonder whether they are behind us, until he spends an afternoon riding roller-coasters. Stuart, who is 14, starts complaining of a violent headache. He’s been waking up with nausea for a month. We relate this to the pediatrician—the mention of the nausea, in particular, causes her to turn on her heel and order an MRI.

My son is diagnosed with two brain malformations: Chiari I, which translates to a skull that is too small for the brain, and basilar invagination, a condition in which a vertebra at the top of the spine moves into the brain cavity and compresses the brainstem and spinal cord. The head of UCLA’s pediatric neurosurgery tells us he can fix the Chiari but wouldn’t touch the basilar invagination “with a ten-foot pole.”

A week before his 15th birthday, Stuart has a piece of his skull removed to allow his brain some breathing room. Over the course of several weeks his symptoms appear to improve, before they return with a vengeance. He stops attending school and is prescribed opioids for the pain. He can barely walk.

My marriage doesn’t survive. But we still form a united front when it comes to Stuart. The UCLA surgeon is at a loss, so we seek out another geneticist. We tell her about Caitlyn, wondering whether there was a connection between her and Stuart’s brain malformations since both malformations are congenital and involve the Central Nervous System. She says they aren’t.

Stuart and I fly to New York for another consultation with a supposed miracle worker I’ve read about in an online support group only to realize we’ve been woefully mislead. (After a nine-hour wait in the Chiari Institute waiting room, the neurosurgeon who evaluated Stuart tells us he couldn’t do anything about the basilar invagination but would like to try an experimental procedure on my son’s spinal cord. “I’m so confident in the surgery,” he tells us, “I’ve even performed it on my own son.” We learn later that the online “support group” is phony and run by the Chiari Institute’s marketing department. The institute eventually comes under scrutiny and the surgeon is sued for medical malpractice by numerous former patients.)

After several more phone consultations with neurosurgeons in Great Britain and the U.S. and further research, I finally find a neurosurgeon who is able to perform the basilar invagination surgery. We travel to Iowa City, Iowa, to meet with him and he describes the high-risk surgery and extended recovery involved.

The Healthy Child

Just after Stuart was born, Steve and I discuss whether to have more children with my in-laws. Steve’s dad offers unexpected, unsolicited, harshly worded advice: “You’ve aborted the retarded baby and had a defective baby, maybe you should just stop at one?” His cruel remark and my own “wanting to get it right” instinct leads me to want to try again sooner rather than later. Steve’s not opposed to more children; he just thinks we should wait a year or two. “Stuart’s a handful,” he says, and “your mom has cancer, and I just started my new job.”

That all makes perfect sense, but let’s just say that nursing is an unreliable form of contraception. We learn we were expecting again soon after Stuart’s first birthday.

Spencer is born December 23, 1993 without complications. He’s chubby and pink, sleeps like it’s nobody’s business and as he matures, he proves to be everything Stuart is not: an early walker, easy-going, athletic, lighthearted, and most notably, healthy. Oh, sure, there have been a few broken bones, and a scary night in the ER for whooping cough, but relatively speaking, he’s my wash-and-wear child.

It’s 20 years later, in 2013. Spencer is a college student in Bellingham, Washington, and complains of a severe headache with nausea and vomiting. My second husband, Ain, and I travel to meet him in Portland, Oregon, where Stuart is attending college. When Spencer begins to shake uncontrollably, we rush him to the ER. We explain his symptoms to doctors and, mention Caitlyn’s and Stuart’s medical issues. The ER doctor immediately orders an MRI. Two days later, Spencer is diagnosed with a congenital condition called cavernous venous malformation (CVM), a golf-ball-size tangle of veins and arteries deep within his brain. The CVM bled, which was what caused Spencer’s headache.

I take Spencer to see a vascular neurosurgeon in Seattle who specializes in microsurgery. After looking at his MRI, he explains that given the location of the CVM, surgery would be high risk and could do more harm than good. He says since it was a one-time event, we might want to take a wait-and-see approach, recommending an MRI every six months.

Spencer’s MRIs show little-to-no growth over the next three years. He goes mountain-biking at every opportunity, works on his engineering degree, is named employee of the year at the campus outdoor center two years in a row. However, the frequency of his headaches is increasing, though none rises to the level of a high-risk brain surgery. Everything seems more or less okay. Until a fateful call from my ex-husband, Steve. His tremulous voice immediately tells me something is wrong.

Ain and I arrive at Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center ICU around noon the next day. Spencer has suffered a hemorrhagic stroke. Steve recounts to us details of the emergency airlift from Bellingham to Seattle as we watch our son sleeping, his arms and legs in restraints, an IV hooked up to his left arm. I sit down and cusp Spencer’s hand with both of mine. He does not respond. Over the next hour, he occasionally mumbles gibberish, something about a goat farm and Fidel Castro. Suddenly, without warning, Spencer bolts upright with all his muscles flexed. He pulls his left hand free of the restraint and yanks the IV out of his arm, and thrashes about trying to free his other limbs. Ain, the nurse, and I try to hold him down. The nurse yells for a crash cart. An orderly and Spencer’s roommate, Nick, join in the effort to restrain Spencer while the nurse frantically attempts to restart the IV. A doctor comes and lifts Spencer’s eyelid to reveal a fixed and dilated pupil. The sound of plastic bags being ripped open fills the room. We all hold our breath except for Spencer, who is now gasping for air, his skin turning scarlet red then deep purple. His bare chest heaves revealing every rib. I watch on from the foot of the bed while pressing his feet into the mattress. Time is collapsing. I’m losing him. Then the nurse shouts, “It’s in.” And the doctor orders propofol, then more propofol, and more still, until finally Spencer’s body relaxes enough to insert a breathing tube.

They perform an emergency craniotomy. Three days later the neurosurgeon tells us the “wait-and-see” period has come to an end.

Search for Answers

Stuart and Spencer have each survived their multiple brain surgeries. Stuart graduated from college with a physics degree and now works for NASA. After nearly a year of rehabilitation, Spencer returned to college, something his doctors predicted would never happen. Both of them suffer physical side effects from their respective operations: Stuart has mobility and chronic pain issues; Spencer has a short-term memory deficit. But they’re alive and I still get to love on them.

You might be asking yourself, as I have over the years, what are the odds that I’d have three children with what doctors say are unrelated brain malformations? I’ve never been good at math but I’m pretty sure the odds are astronomical. I also believe the odds that they are related are far greater than the odds that they are not. My own hypothesis is that my exposure to chlorpyrifos caused the anomalies in all three of my children.

After filling out an online questionnaire offered by Birth Defect Research for Children, I consult the organization’s director, Betty Mekdeci, again to get her thoughts on my family’s history. “You have three malformations that are very similar in that they are affecting the brain and could have the same etiology, that is clear.” I press her about my chlorpyrifos hypothesis, and while she is careful not to give it her full-throated endorsement she explains that because of its chlorinated structure, chlorpyrifos can be stored in body fat, and that there is a possibility I harbored what she calls a body burden.

“You go to the body’s resources to build a baby,” she explains. Fat is one of those resources and studies have shown that, for instance, dioxin—a chemical contaminant that is a byproduct of the chlorpyrifos production process, and one of the most potent and poisonous contaminants (it’s in Agent Orange)—has been detected in body fat and seminal fluid 30 to 40 years after exposure. Questions about grandparents were recently added to the birth defect registry questionnaire, because of what is believed to be dioxin’s multigenerational effect on the immune system. Mekdeci goes on to explain that certain enzymes are known to play a role in the detoxification of the body, and certain individuals lack these enzymes. She suggests that I submit my 23andMe raw data on the Genetic Genie website and see if I might be one of those individuals.

It takes less than 10 minutes to upload my data, receive my “Detox Profile,” and discover that I have a gene variation known in genetics parlance as GSTP1 i105v rs1695 GG. Translated, my body does not produce enough of detox enzymes that protect cells against the toxicity of many compounds including pesticides, heavy metals (present in many pesticides), herbicides, solvents, steroids and many other harmful environmental pollutants. In fact, some health professionals recommend individuals with my genotype minimize their exposure to pesticides and heavy metals.

In summary, here’s where my search for answers has led thus far:

- I’ve had three children born with malformations that are very similar in that they affect the brain.

- The majority of birth defects are due to a genetic susceptibility that is triggered by the presence of a toxin.

- I’m genetically predisposed to be more sensitive to and less able to detox from exposure to pesticides and the heavy metals often found in pesticides.

- I was exposed to a pesticide (chlorpyrifos) early during my first pregnancy.

- Chlorpyrifos exposure is known to be associated neural tube defects.

- Neural tube defects (which Caitlyn had) occur within first 30 days of gestation.

- Chlorpyrifos exposure can lead to DNA methylation (mutations) in genes.

- Hypospadias, hiatal hernia, ptosis (all of which Stuart had) are associated with chlorpyrifos exposure.

- Structural anomalies of the brain (which Spencer had) are associated with chlorpyrifos exposure.

Conclusion

Why does all this digging up of my past and the chemical industry’s sins matter other than to satisfy my own curiosity? It matters because Stuart and Spencer, now 26 and 24, may want to have families of their own one day and I want to do everything in my power to ensure that what happened to them doesn’t happen to their own children.

More broadly, it matters because the Trump administration is engaged is an all-out assault on the agencies charged with using independent, unconflicted science to protect our nation’s public health. Chlorpyrifos is but one example. Lead, arsenic, ozone, beryllium, silica, are others. Most recently, the administration announced it may lift a major Obama-era clean air regulation on the emission of mercury—a pollutant linked with damage to the brain, to the nervous system and to fetal development. The Trump administration should be protecting the public from known (and emerging and future) threats to our health, safety, and well-being. Instead it is loosening EPA, CDC, FEMA, NOAA, USDA, and OSHA regulations rather than enforcing or tightening them, all because the administration and many in Congress are bought and paid for by the chemical, agricultural and other big-money business interests.

The story of my family is the canary in the coal mine. I am sounding an alarm so that no one else must endure the pain and suffering that my children and I have, all because I innocently used an off-the-shelf insect spray 30 years ago.