Female candidates championing the cause, and even sharing their own stories of harassment or abuse, may be seeking to align themselves with other survivors, but at what cost?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Mary Barzee Flores’s campaign ad for Florida’s 25th congressional district is not your typical series of shots with stiffly posed family gatherings and awkwardly listed policy positions. It begins, instead, with Flores’s history of dealing with difficult men, from “handsy customers” to an assault by a boss to a judge who made an insensitive comment—“a crack about my looks”—on her first day of court as a lawyer. It takes 55 seconds before Flores mentions a single policy position—pro- “civil rights and a woman’s right to choose”—she spends the rest of the time aligning herself with the powerfully vocal #MeToo movement.

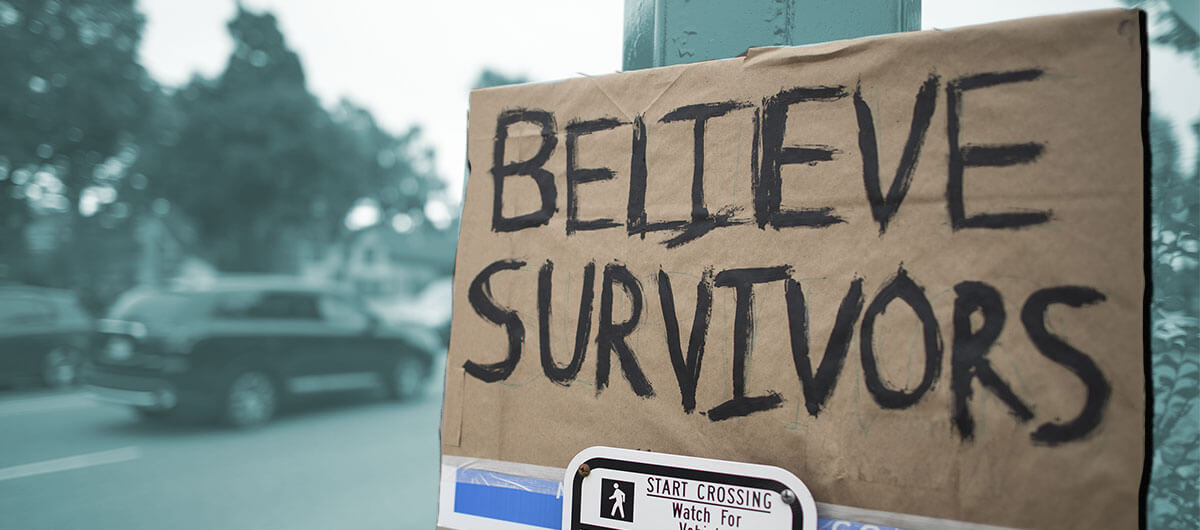

#MeToo has shown itself to be a powerful method of interrogating political structures that already exist, as we saw in the conversation around the hearings for newly appointed Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh. Despite ultimately failing in its goal to block Kavanaugh’s appointment—or at the very least ensure his accusers’ stories were investigated, rather than brushed off as female hysteria—it has sparked questions about entitled frat boy culture, and how someone treats women reveals something about their character that may prove to be useful in challenging future political candidates and judicial appointees. But it has yet to show itself to be capable of building something new.

Since October of last year, when the #MeToo movement began toppling powerful men in Hollywood, D.C., and New York media, a record number of women have announced that they are running for public office this fall, and many of them, hoping to capitalize on this movement, have folded stories of overcoming harassment and violence into their campaigns. Democrat Katie Porter, a law professor running for Congress in California’s 45th district, in Orange County, talks about being “a victim of domestic violence.” Krish Vignarajah, a former policy director for Michelle Obama who recently lost the Democratic primary for governor of Maryland, spoke freely about “add[ing] my name to the list of survivors” at campaign events. Some Republican women are even leaning into these narratives about themselves and their candidacies: Senate candidate Martha McSally, a retired colonel for the U.S. Air Force, has revealed a coercive sexual relationship she had as a teenager with an adult. Meanwhile, other conservative women, who either can’t or won’t talk about their experiences with sexual harassment, are being told not to run at all, the New York Times reported recently. Meghan Milloy, co-founder of Republican Women for Progress, notes the hostile and unsupportive tone toward women in the Republican party, saying, “We’ve told them, ‘You’re a great candidate if it were any other year you would win.’”

This is a hard and fast change from even the election two years ago, when Hillary Clinton employed more masculine speech patterns and body language, speaking more objectively than subjectively and using more absolutes in her rhetoric, in an effort to convince voters she was serious enough for the highest office. But as #MeToo gained prominence, women politicians moved from messages of support for the movement to using their own stories in campaign ads and in their speeches. The candidates and wonks I spoke to, from Michigan to D.C., said it conveys a sense of grit and perseverance—and creates a sense of solidarity with the women in their districts, 81 percent of whom, according to a new survey, have experienced sexual harassment in one form or another throughout their lives. “Publicly telling my story helped to reduce some of the distance between my constituents and myself,” Sol Flores told me. During her race for Illinois’s 4th Congressional District, which includes Chicago, she ran a comprehensive campaign ad laying out her experience and her vision for helping the poor and homeless of Chicago, while also recounting her story of repeated sexual abuse as a young child by a man in her house. “Voters got to see and experience me as a vulnerable and authentic human being. Yes, a woman that had experienced abuse but was not just a victim, rather a survivor.”

But there’s a question, mostly going unspoken, that follows these #MeToo campaigns: Will these tactics backfire on the women who use them? According to a poll conducted in April of this year, a majority of women are somewhat to very concerned with the way the #MeToo movement is being handled, fearing for men who might be falsely accused or be punished too harshly for minor violations. Many women voters seem turned off by the idea of claiming victimhood through gender, despite the majority having faced some sort of gendered discrimination in their lifetimes. The risk is not merely that voters won’t connect with the rhetoric, but that they might penalize politicians who are most visibly associated with the movement.

After a picture of Senator Al Franken groping a sleeping woman on board a C-17 cargo plane emerged last fall, Kirsten Gillibrand was the first woman in the Senate to call on him to resign, pushing him, in a December 6 tweet, to “step aside and let someone else serve” before the ethics committee investigation could investigate. This has created some ill will in the media, as did her comment that had Bill Clinton been president today, he would have had to resign during the Lewinsky affair, with Clinton consultant Philippe Reines calling her a hypocrite and Michael Tomasky at the Daily Beast comparing her to the manic “Off with his head” Queen of Hearts. But many women, at least in the Midwest, seemed to agree that the movement had moved too far, too fast. A majority of women in Franken’s state of Minnesota supported him and, in the weeks before Franken stepped down, stated in a December poll that he should not resign. In fact, the support among women was higher than that among men.

Gillibrand, who has long been accused of using her #MeToo involvement as a platform for a potential presidential run, has seen her approval ratings—both among her constituents and nationwide—drop since the Franken fracas. Even in deep blue New York, many prominent Democrat donors, including George Soros, have spoken out against and withdrawn their support for the New York Senator. “I viewed [her involvement with Franken] as self-serving, as opportunistic—unforgivable in my view,” New York donor Rosalind Fink told The Huffington Post. Candidate for the Minnesota state House Lindsey Port spoke out in November against a state senator who, she said, had harassed her. He eventually resigned, but the backlash was such that she eventually had to drop out of the race.

This isn’t to say that Port and Gillibrand should not have spoken up; Democrats need to counteract the hostile rhetoric coming from the president, a segment of his fellow Republicans, and his supporters. But they need to anticipate the consequences, too: Sensing that many women have turned against #MeToo, some Republicans have begun to try and turn support for the movement into a political weapon. At a rally in Great Falls, Montana, in early July, President Trump imagined tossing something at Elizabeth Warren. “But we have to do it gently,” he said, “because we’re in the #MeToo generation so we have to be very gentle.” Then there was Courtland Sykes, who was vying this spring and summer for the Republican nomination in Missouri’s Senate race. In January, he posted on Facebook about “nail-biting, manophobic, hell-bent, feminist she-devils who shriek from the tops of a thousand tall buildings they think they could have leaped over in a single bound—had men not ‘suppressing them.’” He was running against Claire McCaskill, another prominent woman senator who had just recently thrown her support behind the push to oust Franken.

Part of the reason it’s so easy to paint women in these terms is that it’s not always clear what candidates using #MeToo rhetoric throughout their campaigns are promising their constituents. Is fighting harassment a top priority, or are they merely telling a story? Will women who have faced discrimination and violence know best how to prosecute current cases and prevent future violations?

Some, like Sol Flores, had detailed, well sketched out proposals for reforms that would actually help women, making their lives less precarious and vulnerable, like pay equity and the expansion of health care coverage. McCaskill and Gillibrand do, as well. This is admirable, but rare. Many of the women I spoke to, like Dana Nessel, a former assistant prosecutor in the Child and Family Abuse Bureau for Wayne County, running for Michigan Attorney General, had less substance behind their rhetoric. Her pitch to Michigan voters revolved, almost exclusively, around her gender. “Who can you trust most not to show you their penis in a professional setting?” she asks in a forceful campaign ad that ran in Michigan in November. “Is it the candidate who doesn’t have a penis? I’d say so.” She told me that male attorneys general and prosecutors are “less motivated” to prioritize cases of sexual assault and harassment. Electing a woman, she said, would fix that problem.

This gets at a debate that followed both the Obama and the Hillary Clinton campaigns: Is representation enough? For those who believed Obama’s administration would improve the condition of Black families, his eight years were often a disappointment. His housing policies led to Black families losing a disproportionate percentage of their homes, and Black wealth struggled to recover after the recession in comparison to white wealth. And while Hillary Clinton’s campaign took an overtly feminist tone, her political career has seen her support pro-military, pro-Wall Street, and anti-social welfare positions that have often worked against the interests of a large population of women. Hillary’s failure to win the majority of women’s vote could be seen as a resistance to being pandered to and a rejection of prominent feminists and women commentator’s suggestions that women should vote for candidates like Hillary simply because they are women.

With the rising popularity of far left and progressive candidates, some of whom are beating moderate Democrats in elections, it seems clear a large segment of the electorate is tired of rhetoric and craves action and new ideas. And learning the lessons of the Franken resignation backlash, we can also assume the electorate wants justice—and a full investigation conducted by the ethics committee—not rash action or revenge. Claiming #MeToo alone might not be a sturdy enough foundation on which to launch a political career, but the issues creating women’s vulnerable position at work and in public life just might be. While #MeToo still might prove itself to be a passing trend, issues of violence, workplace hostility, financial precarity, and job instability are anything but.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.