Amid clutter and welfare checks, two old feminist comrades unexpectedly find what others yearn for in the holiday season in a less-than-classic setting.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

The sidewalk garbage cans were overflowing; the front door’s rust-brown paint was peeling; the hallways were low lit and the stairs were steep. Five flights. Susan, lugging her oxygen tank, did it daily.

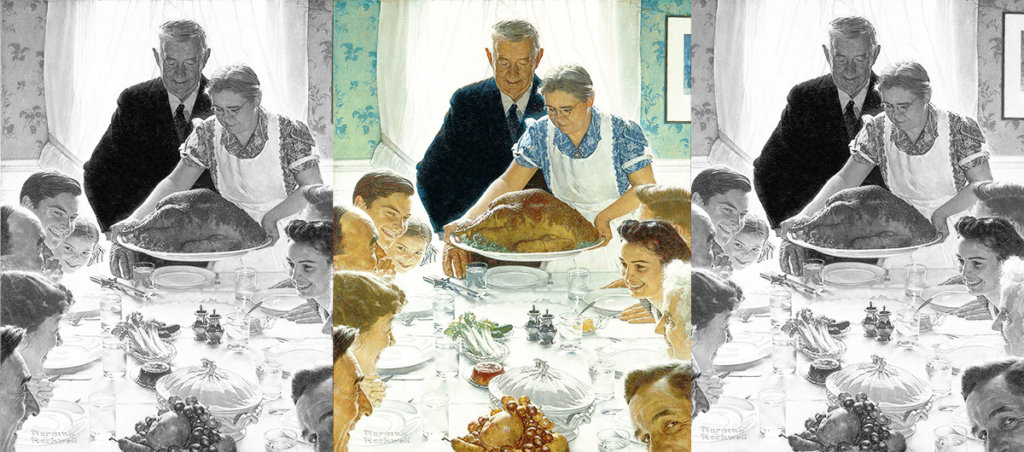

Elsewhere, the tyranny of Norman Rockwell’s happy-family myth is driving some people I know to endure screaming out-of-control toddlers, sniping sisters-in-law, soused uncles, and blindly self-involved parents, all in the name of “the holiday.” I have done so myself, overeating and clenching my fists, but this time, cloaked by a small sense of doing a good deed, I am visiting a brilliant photographer, a decades-long comrade in spite of our often-interrupted friendship who has been diagnosed with cancer and lives on welfare benefits.

Susan is small, dark, intense, feisty, antic, funny, brave, independent, compelling, maddening, confrontational and an all-time original, eons ahead of her time. She rented a shop window and lived in it 24/7 long before performance art had a name. She wired a house for sound and video before reality TV existed. Once, when I worried about money, she had me strip and lie on the floor, draped my body with dollar bills, and made images I’ll never reveal. More publicly, her photographs document important historical moments like marches and demonstrations in the late 1960s and early 1970s and the anti-nuclear women’s peace encampment in England at Greenham Common. Often, hers are the only images of these events, which mainstream media did not consider worth recording.

When we met, we were not mainstream people—we were young white women in our 20’s, sprawling in various apartments, smoking cigarettes and talking about our lives, our orgasms or not, our husbands and lovers, our mothers, our jobs or our work, peace and war, our abortions and the revolution we sincerely believed lay ahead. We were making movies, writing poems, starting magazines, studying economics, organizing demonstrations or, for the lawyers, defending draft resisters and other political prisoners.

The same Susan I have always known unlocks three locks and opens the door on the fifth floor. A hug that is really a hug, far from perfunctory. Serious eye contact. Same fire in her eyes, only slightly tamped down. A one-room apartment, clearly carved out from something larger, consisting of a bed/divan covered Indian or Tibetan fabric, several chests of drawers, sink/stove in the corner and a window opening to a fire escape, which she insists we climb out on and twist our bodies at perilous angles for a narrow view of the East River. Inside, there is the same chaos I have seen in her other abodes—film cans, contact sheets, cardboard boxes, scarves, socks—but a cleared off table, set for two. No cooking smells, which is puzzling, but knowing Susan, a sizzling turkey might soon appear like a rabbit out of a hat.

The revolution has not happened, but Susan has not given up, at least not in her thinking. The other women who sat on floors smoking and talking have, on the whole, adapted, found ways to apply their politics, also slightly tamped down, to regular paying jobs in universities, law practices, media, or non-profit foundations. Most have married and had children, even grandchildren, and live now in relatively traditional ways, with substantial two-person incomes and even a country home or two. Not Susan. And not me.

What we have in common, in addition to decades of traipsing through the same universe, makes us former free spirits who could be classified as orphans on these happy family holidays. Neither of us has a current spouse nor live-in lover; no children or living parents. We don’t regret our choices. But the price of remaining an outsider, the economic reality of an off-beat madcap life has resulted in Susan’s dependence on welfare payments, food stamps, and Medicaid. I do not know for sure, but do suspect that financial limitations, coupled with a strong self-destructive streak, left her less than conscientious about healthcare, the ordinary tedium of regular checkups, which has resulted in a relatively late-in-the-game diagnosis of cancer. These thoughts I will never speak, not only because Susan has endured enough blame and finger-shaking from her old friends for years but because what matters now, here at our holiday dinner—still mysteriously absent, prompting me to consider ordering out, in true New York fashion—is here and now, us on this night.

But the oxygen tank on wheels standing in the corner is the elephant in the room. This elephant fascinates me, which feels slightly perverse, but I am curious, as I have always been curious about things we’re not supposed to ask about or discuss in polite society. What does it feel like, taste like, smell like?

“Try it,” Susan says, and I do, putting the pronged plastic plug into my nose and inhaling. I get a breeze, nothing more sensational.

The doorbell rings. Susan answers. After some minutes, during which someone huffs and puffs up five flights of stairs, I hear a conversation in the hallway and she returns with a large container in her hands, sets it on the table and begins unpacking what the charity Meals On Wheels has delivered.

I have a grim vision of hard cheese and moldy bread, but I couldn’t be more wrong. Juicy turkey. Fresh cranberry sauce. Mashed potatoes, gooey with butter. Wholesome salad. Rolls. Even pumpkin pie! All in ample proportions because Susan has ordered two meals!

Have I said how deft she is at bending rules and beguiling people into doing her favors, for things that really matter? She has gotten herself into treatment at Sloan Kettering, one of the best cancer hospitals in the city. The MacBook Pro that gleams on a cluttered old desk has been conjured from I know not where, nor do I ask. And here, an abundant meal, a feast.

All has been merry ‘til now, not a forced, avoidant merriment like some moments at other holidays with other people, determined not to ruin celebrations with talk of trouble or sadness, but genuine fun, like in the old days between Susan and me. This mood breaks a bit when, mouth half full of turkey and cranberry, Susan asks a question about history.

“How many women artists have died in poverty?”

I’m thinking. The answer is not readily available because the question is not often put.

Alice Austen, gender-bending 19th-century photographer, whose Staten Island home/museum Susan and I have visited, came from a rich family, though her work was not discovered and honored until long after her death. Mary Cassat was rich. Georgia O’Keefe started out very poor, but made a lot of money. Berenice Abbot always struggled, right to the end. Frances Benjamin…

This is not an offhand or academic question. Susan is trying to put herself into history, looking for links that might help us understand our own lives, as women of our generation do, having been the ones to uncover that history for ourselves.

I promise to study the subject and let her know.

Containers in the trash for recycling, dishes washed in the rust-stained sink, leftovers packed in a Ziploc bag, Susan wants to show me something before I go and leads me to the Mac, where she has been busily perfecting the new art of drawing on the screen with the stylus. She scrolls through images of faces, many seen at odd angles or with slight distortions, like some of her old photographs. Then she makes a new image, while I watch silently.

Susan draws a remarkable portrait of herself, sitting cross-legged in the lotus position. Above that figure, she draws another just like it, smaller, ascending, with a halo hovering over her head. One keystroke and what I will always think of as “Susan Buddha” travels from her computer screen to mine, across town, waiting.

If you could peer inside my brain as I walk toward the cross-town bus in the chilly night with leftovers under my arm, passing frustrated people with screaming toddlers in tow waving madly for taxis, this is what you would see: young Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney dressed as hoboes, baggy clothes, smudgy faces, an old vaudeville routine, singing: “Though we ain’t got a barrel of money/maybe we’re ragged and funny/but we’ll travel along, singin’ our song/side by side.”

Side by side is a good definition of happy holidays.