The movement isn’t about vilifying men. It’s about protecting all survivors of sexual harassment and abuse.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

The #MeToo movement is often presented by the right as an attack on men. MeToo accusers, supposedly are “man-hating feminists.” These radicals, we’re told, sling false accusations and smears at upstanding men like Brett Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court nominee accused of attempting to rape a girl at a party when he was 17 years old. Trump advisor Kellyanne Conway explained we “saw in [Kavanaugh] possibly our husbands, our sons, our cousins, our co-workers, our brothers.” If conservatives let Kavanaugh’s nomination go down to defeat, no man anywhere would be safe.

New allegations against powerful Bohemian Rhapsody director Bryan Singer, though, are a reminder that protecting abusers is not the same thing as protecting men and boys. On the contrary, protecting abusers puts many men and boys at risk. If you stand with husbands, sons, cousins, co-workers, and brothers, you need to stand with #MeToo survivors, not against them.

Rumors about Singer have been circulating for years. He was the subject of a lawsuit all the way back in 1997 alleging that he had forced boys as young as 14 to strip naked for a shower scene in his film Apt Pupil. A new article in the Atlantic by Alex French and Maximillian Potter, however, is the first exhaustive investigation into Singer’s history of abuse.

That investigation is searing. French and Potter interviewed more than 50 people, and their sources paint a picture of a man who regularly groomed, slept with, and forced sexual contact on underage boys as young as 13.

Singer’s accusers are male. But their experiences are chillingly similar to #MeToo accounts of women and girls in Hollywood and elsewhere. Like Harvey Weinstein and R. Kelly, Singer is accused not of one or two acts of abuse, but of a pattern of abusive conduct. In Singer’s case, the article alleges he participated in orgies with underage boys, and his network of enablers who ingratiated themselves by introducing him to new potential victims.

According to his accusers, Singer, like other powerful men, did not have to be that secretive. Lots of people knew what was happening. But no one was willing to challenge someone with so much wealth and influence. Cesar Sanchez-Guzman, who has filed a lawsuit against Singer, says the director told him, “Nobody is going to believe you,” after the director raped him in 2003, when Sanchez-Guzman was 17.

Powerful abusers have good reason to think that they will be believed and their victims will not be. Bill Cosby had been accused of rape and sexual assault all the way back to the 1960s. But it wasn’t until a viral skit by comedian Hannibal Buress in 2014 that his career was seriously harmed. Multiple allegations of sexual assault and harassment were not enough to derail Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination.

And of course, Trump himself boasted on tape about sexually assaulting women, many of whom came forward to confirm that he had done what he’d bragged about. He won the presidency anyway. Now his history of sexual harassment is rarely mentioned, even by critics.

Philosopher Kate Manne explains in her book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny that abusive men benefit from “himpathy.” Men, and often women too, find it easy to identify with men, and to put themselves in their shoes.

Thus much of the discussion of Kavanaugh focused on how the accusations would affect him. The damage he had caused his accuser, Dr. Christine Blasey-Ford, is barely mentioned; Kellyanne Conway does not say that Blasey-Ford reminds her of her daughters, her friends, or even of herself. “This tendency to dismiss the female perspective altogether, to empathize with the powerful man over his less powerful alleged female victim, is what I call himpathy,” Manne says. “It’s a refusal to take the female perspective seriously, and it amounts to a willful denial rather than a mere ignorance.

Manne is careful to say that himpathy directs empathy towards powerful men in particular. In fact, the focus of empathy on powerful men helps to create a myth that all men are powerful. It encourages us to believe that the truest, most iconic men are people like Kavanaugh and Trump and Cosby and Singer—people of status, wealth, and influence, who may be accused of abuse. It is Kavanaugh who is every cousin, brother, and husband; it is Trump who is all men.

But Singer’s accusers, and the accusers of actor Kevin Spacey, have a lot more in common with Trump’s victims than with Trump. And in general, men and boys are more at risk of sexual harassment or abuse than they are of being falsely accused. Researchers believe that about 1 in 6 boys experience sexual abuse before the age of 18. In addition, of course, men can also be the victims of rape and assault. Actor Terry Crews, for example, came forward recently to say that he was groped by Hollywood talent agent Adam Venit. Some researchers have even argued that, using broad definitions of sexual violence and coercion, men and women experience sexual victimization at comparable rates.

Whatever the exact numbers, there’s no question that men and boys are victimized far more than they are falsely accused of sexual abuse. Only 2 to 10 percent of sexual assault accusations are false—and of course, far fewer than 1 in 6 men are accused of rape or sexual assault in the first place.

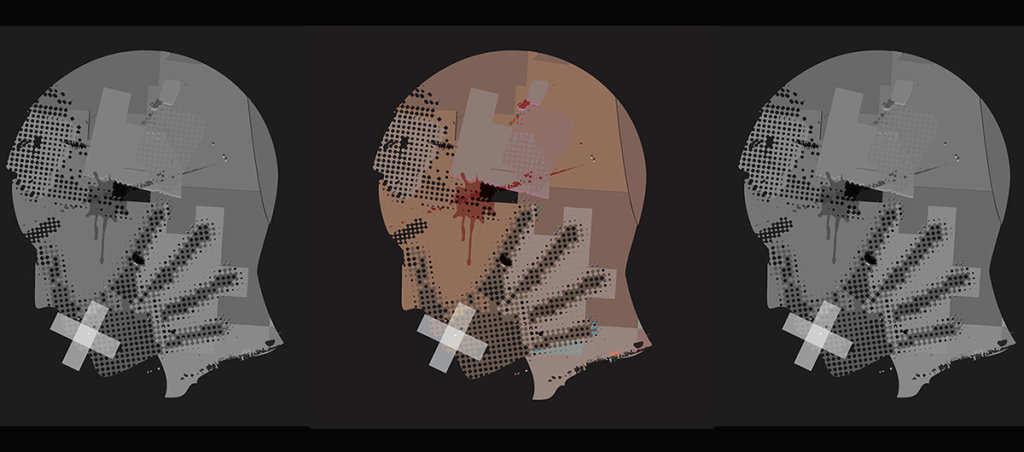

When people rush to the defense of Kavanaugh or Trump or Singer, they say they’re fighting to protect their husbands or sons. But the truth is that protecting abusers puts boys and men at risk. The rush to sympathize with powerful men accused of sexual assault erases the stories of women and female victims. But it also erases the stories of boys and men who have suffered sexual assault. It even, in many cases, erases their very existence. If you see all men in Kavanaugh, you can’t see Bryan Singer’s victims at all.

The fact that men aren’t supposed to be victims can add an extra level of shame. The American Psychological Association writes that men are traditionally supposed to exhibit “stoicism, competitiveness, dominance and aggression”—they’re supposed to be strong and tough. Men or boys who are victims may feel that they’ve failed at being men. The idea that all guys are supposed to be powerful can make it impossible for boys or men to speak out when someone exercises power over them.

The ideal man in our culture isn’t just supposed to be powerful; he’s supposed to be straight. Fear of homophobic reactions can also prevent male victims from talking about being assaulted by men. Sanchez-Guzman felt he couldn’t tell his parents about the assault because they did not know he was gay. The Catholic Church sex abuse scandal was enabled in part by the church’s desire to hide evidence of homosexuality among its clergy.

#MeToo reveals the ugly underbelly of a culture which empathizes with and worships, male power and patriarchy. But questioning patriarchy isn’t an attack on men—for many men, as for many women, #MeToo is a lifeline, a promise that finally, maybe, someone, somewhere will listen. When you protect and identify with Weinstein, or Cosby, or Trump, or Singer, you aren’t standing in solidarity with men. You’re standing with the patriarchy, and against its victims of every gender.