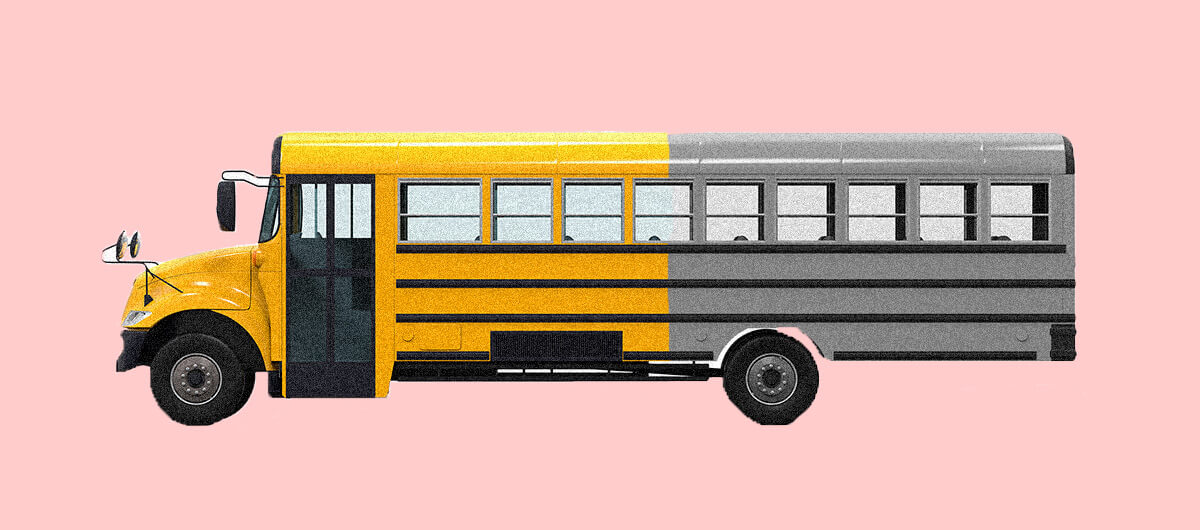

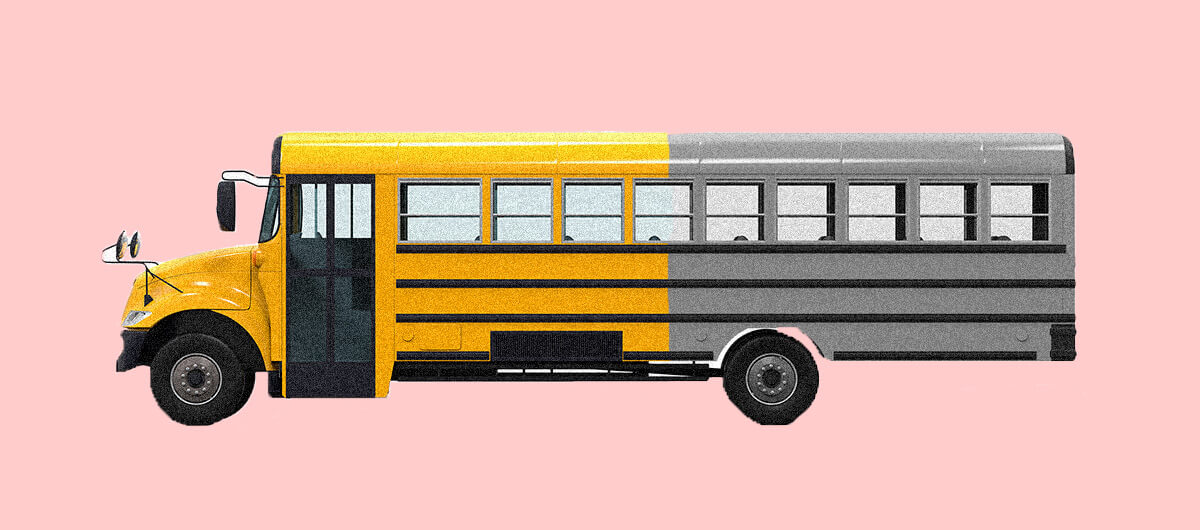

Miseducation

The Unrealized Dream of School Desegregation

Creating equitable education isn’t just about combating segregation with a diverse student body. It’s about equal access to resources, restorative justice, and representation.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Leanne Nunes doesn’t skip a beat when asked if she ever has conversations about the difference between desegregation and school integration. “All the time,” she replies.

The 17-year-old high-school senior from the Bronx works as the director of equity for IntegrateNYC, a youth-led non-profit working for integration and equity in the New York City public school system. Nunes, whose family immigrated from Jamaica, has been involved with the organization since the ninth grade.

Desegregation is what happened after the landmark Supreme Court Case, Brown v. the Board of Education. After the Court declared “separate but equal” illegal in 1954, Black students in the South began to attend white schools, often under extremely hostile circumstances. Integration, on the other hand, is what Nunes and her peers are fighting for in 2019. “Separate is #stillnotequal” is splashed across the top of IntegrateNYC’s website.

“Integration isn’t just the movement of bodies, it’s also the movement of minds and the reformation of policy,” Nunes adds. “It’s not just about who’s in the school; it’s also about the relationships we have at school, and how we equitably redistribute resources so that youth and communities that previously didn’t have opportunities now have those opportunities.”

Relationships and resources are two of the “Five Rs” that make up IntegrateNYC’s policy framework. The other three Rs are race and enrollment, restorative justice, and representation. The students want high schools that reflect the diversity of the city, policies that do not criminalize students of color through school discipline and policing practices, and teachers and staff who look like them.

The framework came out of conversations IntegrateNYC’s youth council had with young people representing all five boroughs. “We would talk about our personal experiences, what we’ve gone through in our school environments, and the things that we wish we would have had in terms of support in our schools,” says executive college director Julisa Perez, who is currently a junior at Brooklyn College.

The students’ own experiences informed the policy framework. Nunes has attended public schools, both in and out of New York, since late elementary school. She describes decrepit buildings, old bathrooms with cracked and dirty mirrors, crooked steps, and walls with chipped paint. Most of the schools she attended didn’t have any technology or had very limited access, and many didn’t use textbooks. “I’ve seen the same things happening over and over, which is that predominantly Black and Latinx schools don’t get what they need,” Nunes says.

The “Five Rs of Real Integration” framework recognizes that solving educational disparities isn’t just a matter of more funding. Minority students attending predominantly white schools might have more access to resources, but there are many other social and emotional factors that also impact their school experience.

Perez has always attended predominantly white schools. As a Latina, she remembers being shy when asked about her ethnicity. “There were instances where I would feel a little bit uncomfortable or like I didn’t really have a space to be authentically myself, but I thought that was just the school experience,” she says.

It wasn’t until a high-school teacher organized a school exchange with a predominantly Black and Latinx school that she realized just how segregated her school experience had been. “I knew that I was attending schools that were well resourced, but I realized that some of the things that happened weren’t just the school experience. I was never supposed to feel alienated or like I couldn’t say my background,” Perez says.

Although white students now make up less than half of the 50 million students enrolled in the K-12 public- school system, racial and economic segregation has increased steadily since the early 1990s, according to UCLA’s Civil Rights Project. Segregation is particularly acute in urban areas, especially for Black students. In addition to declining birth rates among white families, the changing demographics of public schools largely due to a rapidly growing Hispanic population. In states like California, white students make up only one-quarter of K-12 students.

Nearly two-thirds of public-school students attend schools where at least half of the students are of their same race or ethnicity, according to the Pew Research Center. White and Latinx students are the most segregated. On average, white students attend a school where nearly 70 percent of the students are white, while Latinx students attend a school in which more than half of the students are Latinx.

Students of color are much more likely than their white peers to attend schools that lack financial resources because they are more likely to live in low-income areas. Schools are primarily funded through the local tax base, which means that the kids who need the most resources the most are the least likely to have access to them. This has led to what many researchers call “the achievement gap,” referring to significant disparities in academic performance between different groups of students. (Some researchers prefer to call this the “educational debt,” referring to the historical, the political, the economic and the moral debts that have accumulated over time for students of color.)

For instance, white students are more likely to earn Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate credits, which many higher education institutions will grant college credit for. Around 40 percent of white students have earned AP/IB credits, compared to 23 percent for Black students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Although the benefits of learning in diverse classrooms for all students is well documented, a recent study from Stanford University found that differences in test scores between groups are mainly linked to school poverty. “This implies that high-poverty schools provide, on average, lower educational opportunity than low-poverty schools. Racial segregation matters, therefore, because it concentrates Black and Hispanic students in high-poverty schools, not because of the racial composition of their schools,” the authors note.

A 2018 report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that poorer schools often have less experienced teaching staff, substandard facilities, and less rigorous curriculum. For example, the report noted that only less than half of all high schools offer calculus, “but 33 percent of high schools with high Black and Latino student enrollment offer calculus, compared to 56 percent of high schools with low Black and Latino student enrollment.”

Finding comprehensive solutions to school segregation hasn’t been easy. Desegregation didn’t occur in the South until more than a decade after the Brown decision with federal legislation such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 and enforcement through a series of federal court orders. In 1973, another Supreme Court decision, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, found that the Constitution does not guarantee a fundamental right to education or to “equal” school funding, which reinforced the current funding formula based on local property taxes.

Local control over education recently became a talking point during the Democratic primary debate at the end of June. Chiding Joe Biden over his opposition to busing, California Senator Kamala Harris recalled being part of one of the first elementary-school classes to integrate in Berkeley in the early 1970s.

Biden clarified that he was not opposed to busing, he was “opposed to busing being ordered by the Department of Education” and supported control by local school districts. Harris, on the other hand, called for a greater role of the federal government in addressing educational inequalities, citing a “failure of states to integrate public schools in America.”

The Civil Rights Project notes that the federal government currently lacks any programs dedicated to fostering voluntary integration, aside from a small grant program for magnet schools. For the moment, addressing school segregation and the subsequent disparities remains in the hands of local school districts.

Michelle Purdy, an education professor at Washington University in St. Louis, says that true integration requires diversity of background and experience at every level and “a willingness to engage students where they are. You have to also be mindful of not buying into deficit beliefs about children … You have to fundamentally believe that every child can succeed.”

Successful solutions might also involve asking the real experts for their input. When Matt Gonzales, policy coach for IntegrateNYC, was invited to join New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s School Diversity Advisory Group, he brought students to the table with him. De Blasio convened the group in 2017 in hopes of integrating one of the most segregated school systems in the United States.

“The advisory group, which included about 45 organizations and individuals, really bought into this framework and, and let our young people really lead the conversation about what we should be doing next,” says Gonzales, who is also the director of the Integration and Innovation Initiative (i3) at NYU’s Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools.

IntegrateNYC’s policy framework served as the basis for recommendations for New York City schools put forth by the School Diversity Advisory Group earlier this year, building on some pilot programs implemented in a few school districts across the city. District 15, for example, eliminated screens—admissions criteria such as grades and test scores—in its 11 middle schools in 2018-19. Instead, school placement occurred via lottery weighted towards low-income students, English-language learners, and homeless students, radically altering the demographics of the district’s middle schools.

The work of IntegrateNYC might serve as a model for school districts in other cities. As Gonzales puts it, every district needs to look closely at how it “concentrates privilege and vulnerability.” In San Antonio, where the K-12 school population is predominantly Latinx, administrators have also created new schools where at least half the enrollment is reserved for students from low-income families.

“The way I’ve seen this be most effective in New York City is really deeply engaging communities in conversations and really centering the voices of communities of color who’ve been most directly impacted by segregation,” Gonzales says.

He adds that it’s also important to create spaces to work with white parents: “We are really committed to ensuring that all families feel like the education that their kid deserves is the education that all kids should deserve.”

Sixty-five years after Brown vs. Board of Education, Nunes hopes that policymakers will start to listen to youth, who are, after all, the biggest stakeholders in the public school system. “There’s a phrase we like to say, ‘Nothing about us without us,’” she says.

This is the first piece in our ongoing series on Miseducation in American Schools. Read more about what it’s truly like Inside America’s Segregated Schools.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.