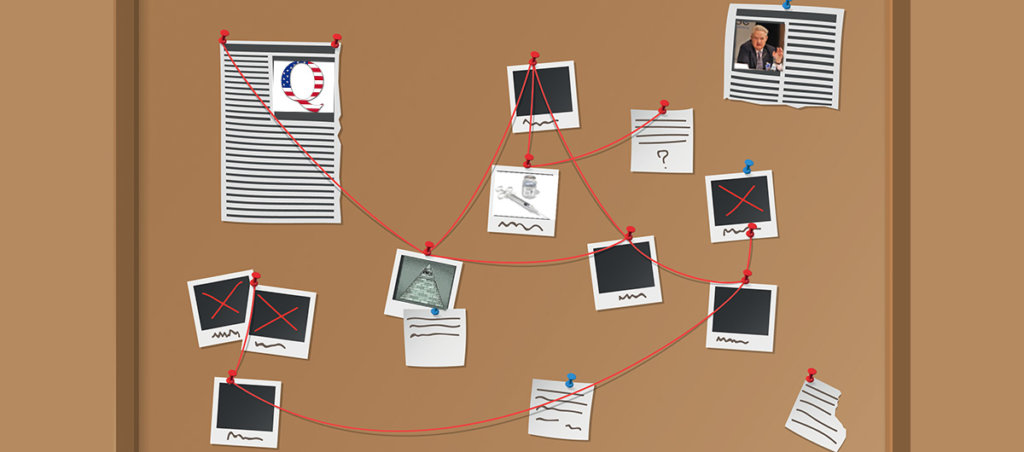

Conspiracy theories, which often espouse hateful paranoia about race and politics, are easily debunked but all too easily disseminated. And that's exactly the point.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

We live in a moment shaped by conspiracy theories and fake news—making it no different from any other moment in human history. President Trump arises every day, takes out his phone, and draws on the ghosts of Joseph McCarthy, Joseph Stalin, and Joseph Goebbels.

A quick survey of American history alone discloses ample evidence of what Kelly M. Greenhill, professor of political scientist at Tufts University, calls “extra-factual information.” While anti-Semitism, birtherism, the anti-vax movement, Japanese internment, Jim Crow, the Spanish-American War, and the violent oppression of Native Americans are fueled by fear and prejudice, all depend on the willing spread of falsehoods presented as fact.

The technology with which we’re able to spread such falsehoods has surely changed, but ultimately, even that’s a matter of degree. Radio, steam-powered printing, and the telegraph all played an outsize role in the spread of conspiracy theories when those technologies were new. It’s a good bet our grandchildren will think Facebook and Twitter quaint.

What’s rarer in American history, though, is this moment’s convergence of extra-factual information and fancy new tech with a political elite, led by but not limited to the White House, willing to advance conspiracy theories with the knowing participation of many in the body politic.

“Right now we’re in this really weird place where we have public figures willing to profess things that are easily debunkable,” Greenhill says. “And for some audience members, that doesn’t seem to matter”—the wink-and-nod with conspiracy theories serving as “a signaling device that ‘we’re on the same side’.”

Absolutely central to this discussion is the fact that Trump rose to political prominence on the back of birtherism—the conspiracy theory that President Barack Obama wasn’t born in the United States and was thus ineligible to serve as the Commander-In-Chief. The iron-clad facts did not matter; what mattered was that Trump and his fellow travelers could use manufactured doubt to delegitimize the country’s first Black president.

Like all good conspiracy theories, birtherism was specific to the moment, and also familiar to those eager to adopt it. Since our nation’s birth, a Black person’s place in American society has been conditional. Under slavery, a free man or woman could be greeted, at any moment, with the demand for their “papers”—proof that their presence in white society was sanctioned. The myth of the “Welfare Queen” traded in similar notions of Black Americans gaming a system not their own, as does the idea that Black professionals advance in their fields as “affirmative-action hires.”

“It does not matter how long we’ve been in these United States,” author and activist Baratunde Thurston wrote after Obama held the press conference in which he literally showed his papers. “We will never be American.”

The anti-Semitism endemic to both the Trump administration and its supporters shares a similar pedigree: Whether it’s khaki-wearing “very fine people” chanting “Jews will not replace us” or Fox News segments smearing “puppet master” George Soros, the chinos and graphics are just modern glosses on a conspiracy theory dating back 1,500 years—one that in the past featured horned Jews conducting ritual murders of Christian children.

Though the expressions of anti-Semitism change as circumstances shift, each new iteration—religious, philosophical, economic, political—is easily adopted and adapted because for centuries, everyone has known that you can’t really trust the Jews: frightening, seemingly inexplicable deaths in your 10th-century French village? Must be the Jews. Frightening, seemingly inexplicable financial disaster in your 21st-century republic? Why look, it’s the Jews!

In times of unrest and anxiety, Greenhill says, extra-factual information “acts as a source of knowledge (that doesn’t mean it’s a source of truth) about the world, and can provide psychic relief and a guide for action.”

“The Nazis knew all of this. They didn’t understand the brain science … but for centuries, those who strategically deployed [extra-factual information] for political or military ends have known it works.”

In his 2015 book Suspicious Minds, academic psychologist Rob Brotherton writes: “Conspiracy theories resonate with our brain’s foibles. But that doesn’t make conspiracy theories psychologically aberrant or unique …. There is no ‘us versus them.’ They are us. We are them. By painting conspiracism as some bizarre psychological tick that blights the minds of a handful of paranoid kooks, we smugly absolve ourselves of the faulty thinking we see so readily in others.”

Which leads, in a roundabout way, to the one thing that is crucially, vitally new to the current miasma of conspiracy theories: the political system in which we experience them.

In the grand sweep of human history, democracy is novel; if we define it as government of the people, by the people, and for the people, candor requires we acknowledge that American democracy is really only as old as the Voting Rights Act of 1965—so, just a little more than half a century in which we’ve been able to fight political manipulation with shared political engagement. No wonder we’re still so bad at it.

But unlike most political systems, democracy presumes faulty thinking—and course correction. Against the surety of human fallibility, democracy has one antidote: a ceaseless striving toward a more perfect union.

In the early 20th century, those who opposed women’s suffrage argued that the responsibilities of civic engagement would literally endanger women’s reproductive organs, and lead to “a degeneration and a degradation of human fiber which would turn back the hands of time a thousand years.” It was pseudo-science dressed in modern terms that drew from an ancient well of misogyny once used to explain everything from crop damage to mad dogs (yes, really.)

Yet despite the familiarity of the conspiracy theory of women’s paradoxical weakness and destructive powers, Americans were able to course correct to something closer to genuine democracy.

Conspiracy theories spouted at lightning speed from the highest office in the land are a threat to all of this. Greenhill’s research has demonstrated that prior exposure to extra-factual information makes people as much as eight times more likely to accept it as plausible; furthermore “exposure to conspiracy theories in which the government is the culprit leads to a lower likelihood of voting in future elections and decreased willingness to proactively engage.”

But the tools that make conspiracy theories increasingly dangerous cut both ways. The speed with which we communicate, the ease with which we organize, and our widely-shared capacity to unveil truths that conspiracy theories serve to hide give engaged citizens a fighting chance.

The key is to remain engaged. To recognize that everyone can fall victim to ideas that are too good to be true, and to call for accountability from those who peddle them, even if they’re on our own side — maybe especially then. (No, the DNC did not crash the Iowa caucus for its own nefarious ends – caucuses are run at the state level.)

Senate Republicans’ recent acquittal of the Conspiracy Theorist In Chief bodes undeniably ill for American democracy. As Rep. Adam Schiff said during Trump’s impeachment trial, “He has compromised our elections, and he will do so again.”

It falls to us, then, to do everything within our power to counter the lies Trump and his co-conspirators tell; to help our fellow citizens remain engaged in the democratic experiment; and prevent the lying liars from stealing it all out beneath us. Aside from anything else, it falls to us to vote.

As citizens in a democracy, Americans are living in one of the very few moments in human history in which we might be able to stop an authoritarian in his tracks. Right matters, and so does the truth.