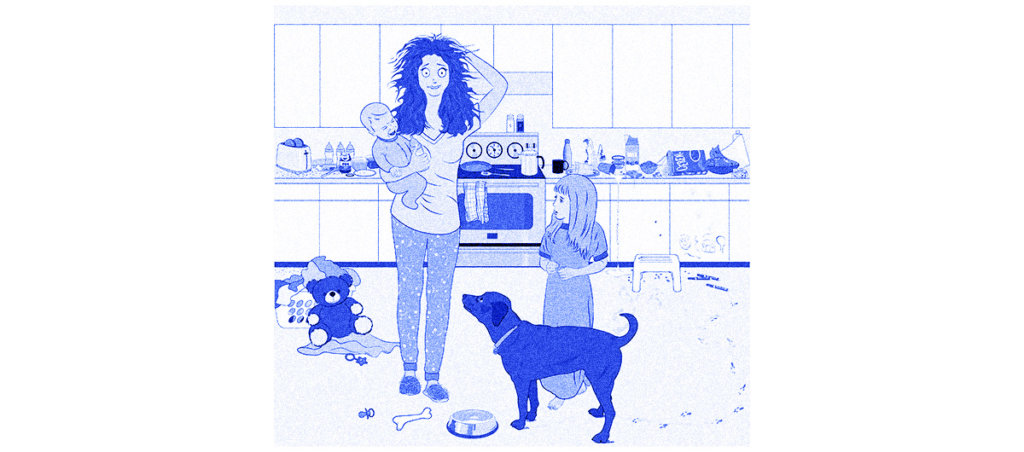

Under mandate to stay home, working parents are now also unpaid teachers and caregivers, with the bulk of the burden falling on women. Are we rewriting a history that took generations to change?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I realized how sick I was when I couldn’t make it to dinner. My husband and I had been home with our 2-year-old since Monday, first “social distancing” and then—when all three of us developed low fevers—self-quarantining. We balanced taking care of our daughter as best we could. He was still doing a full-time job and I was doing part-time contract work that I could fit in around the edges; he was the one who took Skype meetings and I was the one who scooped a laughing, willfully naked toddler who had just learned to undress herself out of his Skype meetings, BBC-interview style. It seemed like it was working.

One day, he was booked solid, and I found myself going past normal stay-at-home parent tiredness. I snapped at my daughter when she begged to stay up past her nap time. I spent our wholesome craft hour lying down with my eyes closed on the couch while she watched Disney Plus. My husband cooked dinner, but when he called us to eat, I was too tired to try. I limped into bed and laid there shivering. When I had enough energy to take my temperature, an hour or two later, it was 104 degrees. The next day was Saturday, so I could rest. But as I heard him, in the next room, struggling to handle a rowdy 2-year-old on his own, the real fear hit me: If I got too sick to work, he’d be forced to do this all the time, and under that kind of stress, he might lose his job or see his own immune system break down. There would be no one to take care of our daughter if we both pushed ourselves past the point of collapse.

It’s one thing to talk about how we undervalue child care and another to see it written out as an equation of life and death. Without someone to take care of the kids, not only do the kids suffer, the parents become unable to work, the family income stops, the physical and emotional resources of parents are drained past the breaking point, and people get sick or die. As the novel coronavirus outbreak has caused schools and daycares to shut down, millions of Americans to lose their jobs, and extended family networks to disintegrate, a vast burden of unpaid care work is being created.

The people who shoulder the burden will overwhelmingly be women. We’re doing most of this work already; women do the vast majority of domestic chores, they are more likely to work part-time to make room for care work, and they are more likely to take time off to care for the newborn, the sick, and the elderly within their own families. I’m fortunate enough to have work I can do from home, but I suspect many women will find themselves in a worse version of my situation: As the secondary earners in their families, free childcare is actually the most urgent service they can provide. Those women will step away from work—or be forced away—and when they re-emerge, it will be to a radically changed economic landscape that may have no further use for them. It’s a lot to worry about, in the midst of a global pandemic, a Great Recession, and a possible genocide, but we may also be on the verge of a reset on gender roles that will last generations.

There are articles on how to “deal with this,” but the “dealing” often focuses on training working parents to excel at their new role as childcare provider. Right now, it feels almost ghoulish to be worrying about color-coded schedules or fun craft projects or training yourself to be a full-on Montessori teacher while also managing to not get fired from a job that (theoretically, for now) still exists. If you’re alive, healthy, and employed, you’re doing better than most people. It is okay to readjust your expectations away from “perfect” and toward “surviving.”

Of course, surviving means keeping yourself healthy enough, physically and mentally, to provide care. Here’s what I’m trying to do: Sleep as much as possible, even if you can only work at night after the kids are in bed, because it preserves your immune system, regulates stress, and mitigates mental health crises. Take naps. Make your kids take naps, or (for older ones who can be trusted alone) make them watch TV or read quietly so you can rest. If you are able to stop drinking alcohol, stop, or cut back; again, alcohol weakens your immune system and screws up sleep cycles, so the more you drink, the more likely you are to burn out or fall apart. Seek professional help when you need it, remotely if possible; look for local teletherapy providers, ask existing therapists to switch to phone or video appointments, or look into apps like 7 Cups, Talkspace, and Betterhelp, which connect you with “trained listeners” or licensed therapists for online counseling. Loosen screen time rules for the kids, but for the sake of your mental health, limit the time you spend reading or watching news.

Yet individual solutions will not save us. Children aren’t meant to be cared for by isolated, atomized units of one or two adults. They are group projects. They require a community. For some of us, our real-world communities are still available, albeit in digitized form. One of the life-saving tricks we’ve used, in quarantine, is setting up a tablet to FaceTime my mother so that she can read our daughter stories and keep her entertained. You may have other moms and parents you can text for emotional support and advice, or a school or daycare that hosts online sessions so the kids can video chat with teachers and each other. All of those are solutions worth pursuing. If you try to do this alone, you will turn into the mom from The Babadook before May, so take whatever help you can get.

Our sense of “community” also needs to expand beyond the people we know. It’s become clear no one will save us. We have to protect each other. Some remnants of an unofficial or official safety net still exist: Organizers have been assembling a state-by-state list of mutual aid efforts. Mary Emily O’Hara has written an excellent explainer on how and when to apply for benefits like SNAP or TANF, even when you don’t qualify for traditional unemployment benefits. Your own area may have food pantries or food banks. But for the most part, our system is unprepared for a crisis like this, which means we need to create those safety measures ourselves in the very near future. Universal basic income, student debt forgiveness, and Medicare for All are all newly urgent ideas in this context—but also, with women being disproportionately pushed to provide care and domestic labor, if there were ever a time to organize around demanding wages for housework, it is now. The sheer number of bereaved parents who will need to find a way to keep working—and who may lose large swaths of their family and support network, not just their spouses—means that universal childcare is going to become a necessary emergency service.

The illness that put me in bed turned out to be the flu. COVID-19 is still somewhere out ahead of us, in our future; I don’t know if it will happen, or when, or how bad it might get. Like most people, I fear the worst. There is no point in sugar-coating this. All of us are dealing with overwhelming fear and grief—grief for the people we could have been, for the lives we could have led, for the comfort and security we’re losing, and soon, grief for the dead, who may number in the millions. Parents, particularly mothers, are dealing with that grief while also managing an incredibly stressful situation, and trying to mitigate their children’s trauma. Yet even in the worst moments, we have the capacity to keep fighting, to imagine more and demand better. It’s not about having a perfect schedule or a never-ending book of craft projects or the ability to make your bored, stressed-out children eat apples instead of M&Ms. It’s about surviving this moment, and the next, and the next, and finding ways to help the people in your support network and your extended community do the same. Whatever the world looks like on the other side, it will be very different. We owe it to ourselves to imagine one in which we can survive.