CSU Archives/Everett Collection

Podcasts

CSU Archives/Everett Collection

Episode One: Perilous Waters

The long history of pool segregation: from the pre-Civil Rights Era to modern day defacto segregation

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

- Prof Jeff Wiltse, author of the book Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America

- Prof Victoria Wolcott, author of Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America (Politics and Culture in Modern

Subscribe on Apple , Spotify, Google. (Sticher coming soon).

Transcript:

I never learned to swim, and neither did the kids in my neighborhood. There was no place to swim.

I grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, and during the summer, our parents would put out lawn sprinklers in the front yard. And all the kids would run through them just to keep cool. But there are no public swimming pools or backyard pools. And of course, there were no private swim clubs. I didn’t see my first ocean until I was about 14 years old, on a class trip to Disneyland.

Oceans and beaches seemed exotic to me.

But as I grew older, I began to realize that the white kids in my school that their summers were quite different than my own. It talks about summers at the lake or their backyard pool parties. And for a while I became self-conscious about not being able to swim. I was embarrassed even.

But what I didn’t know growing up in Memphis is that there was a long painful history behind why there were no places for me to swim.

And I also didn’t know that one of the most pivotal moments in civil rights history happened in 1964. At a swimming pool in St. Augustine, Florida, sunbathing peacefully by day and by night, Negro integration marches with sometimes violent reaction today trouble under a noon sun Negro. During the Civil Rights Movement, St. Augustine, Florida was ablaze with civil unrest. There were fire bombings and cross burnings, and violence directed towards the black citizens there and against protesters.

Civil Rights Organizations later said at the unrest in St. Augustine was the most violent and bloodiest campaigns in the civil rights movement.

Committee. Things got so bad that local activists plead for outside help. And finally during the spring of 1964, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, some of their most prominent leaders to St. Augustine.

And eventually, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself join the activists there with Dr. King to remove his influence from the community for 30 days, demonstration seats for the same period.

It was on June 18, 1964, that a group of protesters went to the Monson motor lodge in St. Augustine.

There was actually media coverage of this particular protests and the entire thing was caught on camera.

In the footage, you can see the manager of the motor lodge angrily confronting a group of peaceful protesters. First, he starts to aggressively shove them, including many of the women and a few of the activists managed to jump into the swimming pool. And what happens next, catches everyone off guard.

The manager disappears off-camera, and when he reappears, he’s holding jugs of something. And he begins pouring the jugs of liquid into the swimming pool. It’s later revealed that that liquid was actually acid. Brock told him to get off his private property.

He threw cleaning chemicals inside the pool, there was pandemonium and chaos.

The pool water was so diluted that the acid didn’t seriously harm anyone. But they were scared. And the manager is furious. You can see it in his face and his posture. He’s angrily stalking around the pool pouring the liquid into the water.

And the video of this event was so shocking that it was played all over the country. And even though there was no internet in 1964, you can say that this video went viral. Apparently word of the incident even made it back to President Johnson.

And the very next day on June 19 1964. The Civil Rights Act was passed by the US Senate after an 83 day filibuster.

Later many of the protesters said that they felt that if it weren’t for St. Augustine the Civil Rights Act may not have passed that summer, and if it weren’t for this viral video, this horrific act of violence against peaceful protesters, a video that’s very similar to the confrontations of black Americans, which are still caught on camera today.

If it weren’t for the presence of the media that day at the Monson motor lodge pool, the violence in St. Augustine may have continued unabated. And maybe just maybe the Civil Rights Act would not have passed that summer.

From DAME magazine and the electorate, I’m Jen Taylor Skinner, and this is The Gatekeepers.

Come on in the water’s fine. Rugged looking fellows will keep an eye on you. So Wasn’t there a time before the Civil Rights Act passed where pools were segregated by class versus by race. This is Professor Jeff Wiltse. So prior to about 1920, and it’s there’s nothing magical about 1920, but basically the late 19 teens, early 1920s. So prior to the late 19, teens, blacks and whites swam together at municipal pools in northern cities, but as you point out, the use of pools divide along to other social lines, and so these pools were strictly segregated along sex lines, so males and females did not swim together. And they they also serve their use divided along class lines, the municipal pools that were built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of them were intended to serve as bad or little bit later on. They were intended to serve as recreational facilities But they were intended to serve the poor in the working classes. The pools were located in poor neighborhoods, or at the time, referred to as slums. And in these neighborhoods were inhabited by a diverse range of poor and working class people, including native born whites, European immigrants, and African Americans. And there’s an abundance of evidence not just in Philadelphia, but even in places like St. Louis, which has really sort of a kind of a southern heritage to it, where were blacks and whites swam together in these earliest municipal pools.

And when that changed, when cities and white swimmers in the north began to impose racial exclusion and racial segregation, it was during this period beginning in the late 1910s, up through the 1930s. It was a result of several things one being gender integration when public officials in northern cities began to permit males and females to swim together. White swimmers, white men in particular began to voice their objection to that if city officials didn’t impose a formal form of segregation this goes to the point about policing that white swimmers would police pools and use violence and threats as a means to intimidate black Americans from using those pools.

Once men and women began to swim in the same pools, it’s no surprise that confrontations often violent confrontations began to escalate. There’s a long history of hyper-sexualization of black bodies, and the intimacy of swimming pools exacerbated those tensions, especially in relation to black men. To put it simply, white swimmers did not want black men interacting with white women in such intimate public spaces. Is anyone who’s been to a pool. I think, too.

Intuitively understands that swimming pools are very intimate spaces. They’re visually intimate, in that you see people in a public setting, mostly unclothed. And the only thing equivalent to this would be really at the seashore.

They’re also physically intimate. And this is one of the ways in which pools are sort of different than say a seashore is that at a pool, you’re sharing an enclosed body of water with other people. And so the water that comes into contact with you and your skin comes in contact with other people. And also swimming pools are a physically intimate space in that people oftentimes touch one another. You look at people interacting in a pool, and oftentimes there’s a lot of grabbing and touching and so there’s that degree of physical intimacy. And then a third way that pools are intimate is that they’re socially intimate. Unlike again, most other public spaces, people spend a long period of time at pools, they spend hours sometimes most of a day. And that presents the opportunity to socialize, to chat for young people to make a date with one another and get to know one another. And so for that reason, swimming pools historically have always been sort of socially contested spaces, and so that their use historically has divided along sex lines. It’s divided along class lines. And of course, it’s divided along racial lines as well. And in a lot of that has to do sort of the extent to which the degree to which swimming pools historically and even today are contested spaces has a lot to do with that intimacy, the visual, physical and social intimacy involved in their use. We often give these viral videos and the people who police

These public spaces. Cute names like “pool patrol, Paula.” But I worry that those cute names obscure the seriousness and harm of these confrontations. Pool patrol Paula, for instance, was named after a video that went viral in 2018. Where a 38-year-old white woman physically assault a 15-year-old black teenager.

She uses the N-word, she threatens to call the police and see repeatedly assaulted, both verbally and physically. The woman was eventually arrested and charged with assault and battery.

What the conversations about these confrontations often felt approach is the arranger of the teenage boys vulnerability as someone who’s underage, she assaulted a child.

The adult-ification of black children is a pattern that we see in both these current videos as well as in the historical accounts of these confrontations.

Adult-ification is a form of racism and bias for children of color. Often black children are treated as being more mature than they actually are.

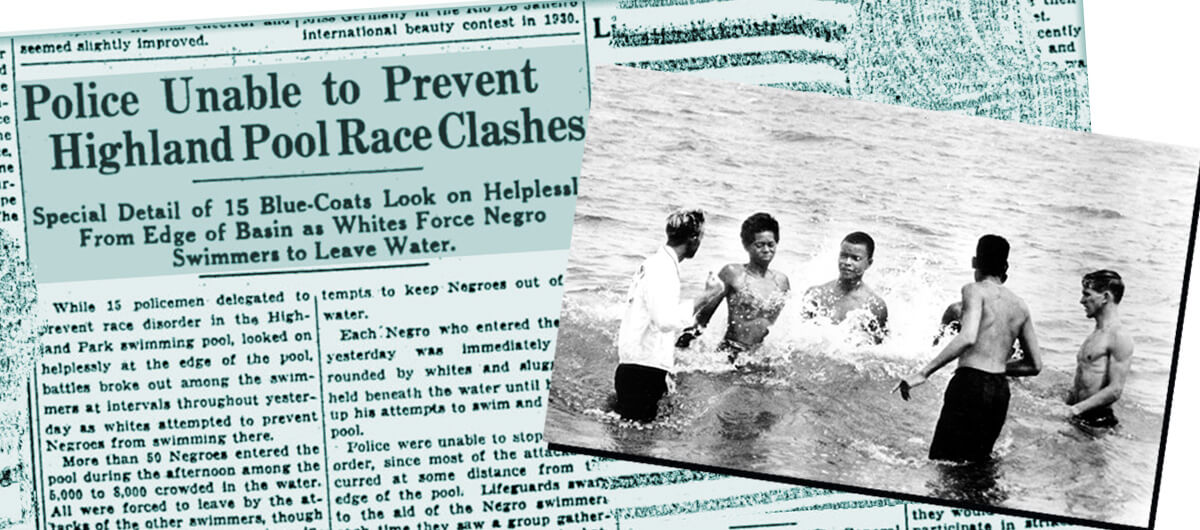

As seen in this video, young people, most often teenage boys, their presence at these places of recreation is treated as something more sinister rather than just a teenage boy wanting to enjoy his summer. So as we explore the historical accounts of policing at swimming pools, we should bear in mind that many of the targets of the violence are just teenagers.

Can you talk a bit about the violence that was directed towards black swimmers when they tried to use these pools? How exactly did the white swimmers try to prevent them from swimming? Yeah, I mean, one of the main points that I’d like to make to you is is that that white citizens policing black Americans at swimming pools has a law

Long, long history. And it goes back to the period in which I was just talking about, which is in the 1920s and 1930s, when swimming pools in the northern United States became sort of racially segregated.

In many states, there were state civil rights laws that prohibited the official or does your segregation of black Americans with the exclusion of black Americans because there was their state laws, you know, prohibiting racial discrimination and accessing public facilities. And so public officials in many northern states could not officially segregate swimming pools. And yet for the reasons that we’ve already talked about having racially integrated use of these large leisure resort pools in which males and females were both using them together was objectionable to large numbers of Northern whites, but

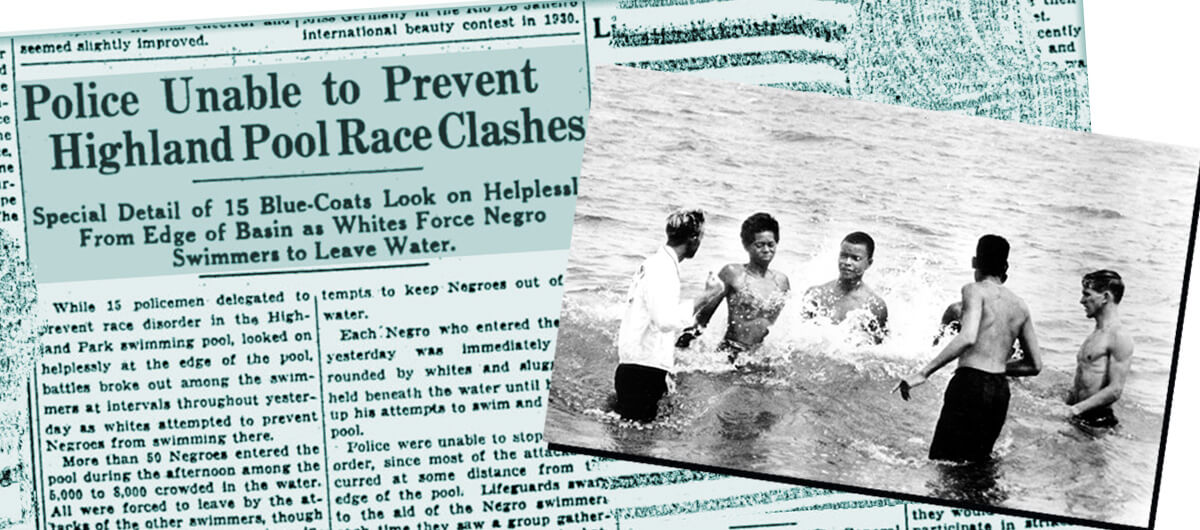

Cities could officially impose segregation. And so white swimmers, basically police these spaces themselves. And pools that had been earmarked for whites or pools that were located in mostly white neighborhoods. White swimmers would use a variety of means to prevent black Americans from accessing them. pools that were located in white neighborhoods. It was intimidating for black Americans even to enter those neighborhoods. And so they might be sort of attacked or beaten up or threatened just by entering those neighborhoods. But for pools that were located in, in more mixed neighborhoods in which African Americans live nearby, the white swimmers would with quite literally beat them out of the water. And sort of some of the best evidence of this. There’s there’s many examples, but some of the best evidence comes from Pittsburgh’s Highland Park pool, which was opened in 1931.

And the very first day that the pool was open, a significant number of African Americans attempted to enter the pool because they had had open access to the previous pools, but the attendance pick each and every identifiably black person out of line and demand to see their health certificate. Well, they were protests that night by the local NAACP. And the mayor says, Oh, you know disavows this and says no, there’ll be no more health certificate requirements. And so in the days after, black swimmers again show up, they enter Highland Park pool, but this time, white swimmers, beat them out of the pool quite literally. They punched them, they kick them, they held them under the water to make them fears though they were drowning. In the next couple of days. Gangs of white swimmers waited outside the place for prospective black swimmers to come and according to reports in the Pittsburgh courier they use sticks and bats and throw rocks at the black swimmers, the prospective black swimmers to intimidate them from trying to enter the pool. And in this way, they were able to effectively establish Highland Park pool as a whites only space.

There’s actually an archived account of the Highland Park pool violence online. It’s in the Pittsburgh post Gazette newspaper dated August 6 1931. And the paper reads, while 15 policemen delegated to prevent race disorder at the Highland Park swimming pool looked on helplessly at the edge of the pool. Battles broke out among the swimmers at intervals throughout yesterday as whites attempted to prevent negros from swimming there. And it goes on to say it’s Negro who entered the pool yesterday was immediately surrounded by whites and slugs are held beneath the water until he gave up his attempts to swim and left the pool. Police were unable to stop the disorder since most of the attacks occurred at some distance from the edge of the pool.

And that account is in keeping with similar confrontations that were happening all over the country. Black swimmers were violently attacked until they left the water. And police often stood by and did nothing. And sometimes they even arrested the black swimmers. So yeah, so so segregation is is you know, what you do to prevent violence in the eyes of these white officials and many white people. And again, I think we live with that legacy that this is pictorial walls were marketed as clean, as orderly and as safe, whether or not that was true, that was how they were marketed. A place like an amusement park, for example. And so therefore, any kinds of presence of African American bodies in that space was inherently thought to be by whites disorderly and unclean and potentially violent. And then by attacking them physically. They made that come true. They create a disorder. There was a video that went viral a couple of years ago of a confrontation at a hotel pool in Pasadena, where a white man confronts a black family and asks if they showered before entering the swimming pool.

Because that was in 2018. The hotel manager gets involved and the white man behaves as if his question is perfectly reasonable. And he says, but those are the rules, as if he a hotel guest has been put in charge of enforcing the rules for other guests.

And one of the black women that he confronted pointed out that he didn’t ask any of the white swimmers if they’d showered first. On the video, you can hear him saying, you know some people treat these pools like baths, and that they should all Google information about the spread of disease and pools.

And that reminded me of another driver for violence and discrimination against black swimmers another layer to the racist policing of their presence at swimming pools. And that’s the assertion that black people are dirty and carriers of disease.

In the early part of the 20th century, some of that anxiety was attributed to the influenza pandemic of 1918. But it wasn’t only about the flu pandemic, the fear of communicable diseases is really just a cover. It’s an excuse for a racist pattern of policing of black people at swimming pools. What started well before the pandemic and continued well after, I think that it’s important to put it into the historical context. So prior to about 1915, there were relatively few African Americans living in the north and living in northern cities. I mean, when you look at cities like Detroit or New York, it was like 1%, or maybe even at most 2% of

The overall population of the city. And instead, those cities were heavily populated by immigrants, immigrants from Europe who were relatively poor, and worked at labor-intensive industrial jobs. And they were perceived the European immigrants were perceived by the middle and upper classes in America at the time as being sort of conspicuously poor, being dirty, and being likely carriers of communicable diseases. Well, what happens beginning in about 1915, and this is very closely tied with the beginning of World War One is that foreign immigration from Europe is declined significantly and that northern industries look to Southern African Americans or African Americans living in the south as a source of labor to replace European immigrants. And so at the same time, that the flood of European immigrants coming into United States sort of slows down to something closer to a trickle. Large numbers of Southern blacks begin moving up north, and they become a much more conspicuous, much larger part of the population of northern cities. And what ends up happening is, is that they, in the minds of many northern whites replace European immigrants as being the most conspicuously poor as being sort of, you know, dirty and doing physically demanding jobs that oftentimes make the labor physically dirty, and also become sort of stereotyped as being likely carriers of communicable disease. And that contributes significantly to the unwillingness of many whites especially in the north to one to share the same enclosed body of water, the same swimming pool with

Black Americans, but the context I think is important. It wasn’t simply that well, these prejudices and these stereotypes were just always and only applied to black Americans. What happens is that during the period of the pandemic, that you’re talking about the influence of pandemic that’s happening at exactly the time in which these sort of prejudices are shifting away from European immigrants and being placed on African Americans, precisely because of these two demographic changes the slow in European immigration and the great black migration that occurred at the same time trying to think Do I have any other instances that are similar? This is my friend Tina. We’ve been friends for years.

And we’re both black women. And whenever we meet up for coffee or drinks, we always talk about race. So when I told her I was doing this series, I knew she’d have some stories to tell me. But it was this one story that she told me about a private swimming pool and her experience there. It just reminded me that the tensions that were present around black bodies and swimming pools, you know, over 50 years ago, are still with us. So here’s Tina. Yeah. I have experienced is, you know, going into a pool and people leaving right away. Have you? Yeah, here in Seattle. You go into the pool and people just leave. Yes. It’s the weirdest thing.

Yeah, we’ll see I can’t swim.. Yeah. Wow. Tell me about that. Yeah, I mean, I mean, it was just one of those things where you don’t know if you’re, you know, if it’s you or you know, I was at a friend’s house, you know, there was the apartment complex had a pool. There was a lot of people outside. And you know, when we got there, they just they weren’t into it. And it’s like a small group of us. I think it was about seven or so of us, and only three of us were in the pool at the time. Wow.

So remember the incident in St. Augustine at the Monson motor Lodge. The subsequent passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, spelled the beginning of the end to pool segregation. At least officially, what happens following the official desegregation of pools explains why there were no swimming pools in my neighborhood growing up, and why swimming wasn’t a part of my life. Northern Lights with my

As these spaces finally start to be integrated because of massive protests and because of the Civil Rights Act, and so by the 70s, right, you have, you know, integration, at least on paper of swimming pools and other spaces. So what happens right away as they become privatized, so pools get shut down or they get turned into private clubs. I grew up in New Jersey, and in the 70s, and you know, every summer you paid like, three bucks or something to join the club for the swimming club. That was because of segregation. That was a way for them to legally exclude people. So people go to their backyard pools, or you haven’t gated communities and homeowners associations where the tennis court or the swimming pool, you have to be part of the homeowners association to use that space. But essentially what happens is that swimming pools public swimming pools in the United States were racially desegregated from about1948 to about 1965. And in the north and in the western United States, public swimming pools were desegregated, you know, between, you know, late 1940s. And then the first part of the 1950s into the mid 1950s. And then public pools were racially desegregated in the south,

In the, you know, kind of the first half of the 1960s. And so it happens in different regions at different times. But what’s important here is the way in which communities and white swimmers react to the racial desegregation of public pools. In the south, what happens is the city’s just closed their public pools, and they won’t, they won’t, they won’t allow even the opportunity for blacks and whites to swim together. And so, in the south, the pervasive response was just to close public pools, which meant then that the only access that people had to pools were private pools, either residential pools or private club pools, which clearly then sort of divided swimming along class lines that only people who could afford to access private pools could now swim. And it goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway, that that black southerners were excluded from accessing the private pools that whites were now using.

In the north, the story is a little bit more complicated, but the end result ends up being pretty much the same, which is that when swimming pools that had previously been used by whites were racially desegregated, and black Americans start using those pools. White swimmers, abandon them in enormous percentages. And so I mean, the cases of St. Louis Warren, Ohio, Baltimore Maryland mean that the statistics that I was able to find indicate that over 95% of whites who had been using those pools abandon those pools and in some cases, sort of no whites use those pools anymore. And so there’s an a general abandonment by white swimmers of pools public pools that began being used by African American swimmers.

Many of those white swimmers, abandoned public pools entirely in many families are moving out to suburbs, and that many white swimmers who abandon public pools after desegregation end up then joining private club pools at which racial segregation racial exclusion is still legal. Or they build swimming pools in their backyards and begin using those. It’s also the case that, that some swimming pools public swimming pools in cities where the pools have been racially desegregate.

It remain whites-only based upon being located in thoroughly white neighborhoods where black Americans can still be intimidated from using those. But what ends up happening is when you get so many white swimmers abandoning public pools, they become much less of a public priority or a priority for public funding. And so funding for new pools dries up and so there’s very, very few new pools built in the United States during the desegregation era, and furthermore, cities begin cutting back on maintenance and upkeep. And when the pools begin to deteriorate and require repairs, cities are no longer willing to pay the cost of repair. And so they end up closing them. And so what ends up happening in the wake of the desegregation of public schools

As you, you know, very succinctly put it is that there’s a divestment in them. And cities no longer fund new pools, and they cut maintenance on existing pools, which leads to a significant decline in the provision of public pools at the exact same moment in which literally 10s of thousands of private club pools are being developed and built in suburbs throughout the United States. And so you get this quite profound shift from the public provision of pools to the private provision of pools. And the effects that that has is one is it restricts access based upon class lines, that you have to now have money necessary to be able to join a private club or build a backyard pool. And it also even more thoroughly than before establishes a racial segregation because the racial segregation that occurred at a private club pools was actually even more stringent than the racial segregation that existed previously at public pools.

I wanted to find out more about the legacy of swimming in my hometown of Memphis. Memphis was central to the civil rights movement. And of course, it’s the place where Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. So I knew there had to be a history there. And as it turns out, there was in a neighborhood called orange mountains. Orange mountain has a long and rich history in itself. It originally sat on about five acres of land that was used for a plantation, and the land was named after the orange hedges, the ones lined the plantation.

When the plantation owner died, his widow sold the land to a white real estate developer. And she instructed the real estate developer to not sell the land to African Americans. But he did it anyway. He sold small pots of land to black Americans, and they built houses

in Orange Mound, the community was born. Orange Mound is the oldest bike neighborhood in the country. And this was around 1890. By 1928, a five-acre park opened in the heart of orange mountain. And eventually they added a large swimming pool. Apparently there were food vendors at the swimming pool. And it was a place where kids and families and neighbors would gather. It was right in the middle of this black neighborhood.

I’m imagining this place this thriving place right in the middle of a city that was notorious for its violence and its racism and segregation. And it sounded like a small utopian. I found a black and white picture of the orange bound swimming pool online. And then the photo you can see these black and brown bodies in and around the swimming pool with a hot sun glistening off of their shoulders. In the photo. There’s a young man he’s in mid air and he’s diving into the pool. And everyone is standing around and they’re relaxed and they’re happy.

There’s no violence, there’s no one asking them for their health certificates. And there’s no one to tell them that they don’t belong.

Well, that utopia doesn’t last. And the spring of 1963, the Supreme Court ordered the city of Memphis to desegregate its public park system. Now that was a huge victory in the fight for civil rights. But to avoid complying with these orders, the city of Memphis decided to close the public pools instead. The orange mountain pool which was once a thriving, gathering space for this black community, a place where they could swim in peace and enjoy the same summer recreation that white citizens enjoyed. It was locked and it sat unused for years.

By 1967, the pool was deemed too costly to keep up so they bulldoze it and filled in the land.

I don’t know exactly where the pool was located. But I do have a closer connection than just growing up in Memphis when I was a little kid about three or four years old – I actually went to the orange mountain preschool. So I asked my mother and some older family members, whether they remember the orange mountain swimming pool.

And no one did.

It’s incredible to me that this once vibrant gathering place in the heart of the oldest black neighborhood in the country was just erased, there was an absence, and that absence shapes my relationship to swimming and the relationship to swimming of other kids in my neighborhood. And for many of us, it probably will for generations to come.

There were two periods in time in which swimming became popularized within the United States. The first period was 1920 to 1940. And, and the the the catalyst for that popularization were the thousands of public swimming pools that were built throughout the United States during this period of time. And as we

Already black Americans had far less access to those pools than did white Americans. The second period in which swimming again became popularized, sort of further popularized was during the post World War Two period really between about 1950 and 1970. And the catalyst for the popularization of swimming during that period, where the 10s of thousands of private club pools that were being developed out in suburbs, and black Americans had virtually no access to those pools. And so what ends up happening is that because of their access to public pools during the interwar years, and private pools during the post war period, swimming becomes a common part of white Americans is recreational culture. And as a part of the recreational culture, it gets passed down from parents to children from generation to generation, precisely because black Americans were largely restricted from their access to the public pools during the interwar years and an entirely excluded from the private club pools during the post war period. Swimming either as a recreational activity or as a competitive sport never became a common part of African Americans is recreational culture. And instead what ends up happening precisely because black children didn’t have access to swimming pools, which where there was lifeguards, and they were relatively safe spaces, nor do they have access to the same degree that whites had to the swim lessons that were be offered at swimming pools. That that black children end up swimming in natural water. They end up swimming in ponds and rivers because they want to cool down during the summer. These are much much more dangerous spaces. And many African American children die of drowning because they’re having to access water.

These unsupervised dangerous spaces. And so what that builds within many African American families is a fear of water that African Americans, and there’s been studies that sort of document this, that a much higher percentage of African Americans have a fear of water and a fear of entering water and it to alarm. I mean, there’s some sort of evidence to suggest that this maybe goes all the way back to the Middle Passage in which African Americans sort of drowned during the Middle Passage. But But more recently, it’s very closely connected with the fact that black children drowned at a much higher rate than white children during much of the 20th century because they were having to access water in an unsupervised and dangerous natural waters rather than it pools. And so what ends up happening is that within many black families, what gets passed down from generation to generation is not sort of a love and an appreciation of swimming and taking their kids to the pool because that’s what they did when they grew up. Rather what gets passed down in many African American families is in fact a fear of water.

When I started my own family, I knew I wanted something different for them. And because I’m married a New Zealander beaches and water, we’re going to be a part of our lives. He grew up surrounded by beaches and water. Our son started swimming lessons when he was about four or five years old. And right before the pinda moquette, he just graduated from the highest swimming level of his Swim Club. He was so proud. And whenever we all go on a beach vacation or to the lake near where we live, my husband and son are so comfortable in the water, and it does feel so foreign to me. And I have to remind myself that the anxiety around watching them, and that my fear of water, it isn’t founded in any real danger, for the most part, and it really just comes down to the history of pool segregation. And the way it shaped my life.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.