While men in Trump's administration have profited from their complicity, women have sounded the alarms at their own risk.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

A co-worker stopped by my office one morning with a heads up. An executive in our organization had been sued for sexual misconduct and the press had caught wind of it. “Stories could start showing up any minute,” she said.

I was googling even as she talked. “They’re already here,” I said, showing her my screen. The complainant was a woman he’d known years ago, at a different company. Her allegation involved the standard mix of implicit quid pro quo and unwanted groping. Honestly, past the initial adrenaline spike, none of it was very surprising. I’d never seen or heard of him behaving inappropriately, but as a veteran of both sexual harassment and corporate life, I assumed any powerful man had at least the potential to turn predator when he felt entitled to something he couldn’t get through civilized channels.

All morning, other co-workers stopped by to process the news. The women felt mostly as I did, surprised-but-also-not. A few of the men, however, were just taken aback that the story had finally come out. “I mean, this was an open secret in the industry,” one man said. “You didn’t know?”

“Sweet fancy Moses, of course I didn’t know!” I said. I had female employees, after all. If I’d known and not said something, I could have been putting them at risk.

“I just figured everyone knew,” he said. Another man echoed him later that day, adding “It’s almost not even news.” At least not to men, apparently. They just hadn’t seen fit to clue in the rest of us.

***

That morning was on my mind as I absorbed the revelations from Bob Woodward’s new book, Rage, about how Trump knew all along that Covid-19 was not just, in Trump’s usual English-adjacent language, “a strenuous flu.” “TRUMP KNEW” was all over my Twitter and Facebook feeds. And Bob Woodward knew Trump knew—had known since February, by his own account. And yet Woodward sat on the information for six months … Why, exactly? “To maximize future book sales” was the most obvious explanation. The most civic-minded one I could conjure was that Woodward wanted the revelations to have maximum Election Season impact. I also knew it could take some time to lock down his reporting. Per Woodward, he was satisfied by May that the reporting was solid, but since Covid-19 had already spread nationwide at that point, he no longer thought telling the story could impact public health.

By May 30, 100,000 Americans had died of Covid. By the time Rage was published in September, the death toll had nearly doubled. Would earlier disclosure by Woodward have made a difference, forced or shamed the administration into action? That’s an open question he chose not to let us answer.

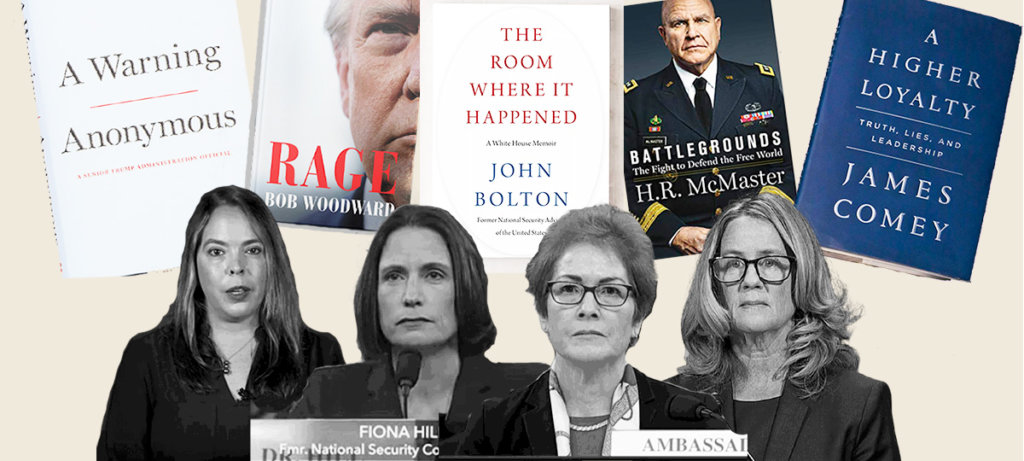

Woodward joins a line of men who have warned the nation about Trump’s moral vacancy and incompetence only when it was most convenient and profitable for them to do so. Ex–National Security Adviser John Bolton refused to testify in Trump’s impeachment hearing, only to spill all kinds of dirt a few months later in his memoir The Room Where It Happened. Trump fixer Michael Cohen (destined to be played by Steve Carell at his sad-sack best when we are inevitably subjected to a movie about this era) was much more forthcoming with Congress, but only when he thought it might reduce his jail time. The anonymous senior White House official who wrote 2018’s bombshell New York Times op-ed about Trump and the 2019 book A Warning is at it again for this month’s updated edition, promising dramatically to reveal their identity “in due course.” (To be fair, Anonymous could be a woman, but women make up only a quarter of Trump’s senior staff and Betsy DeVos doesn’t strike me as the type.)

Meanwhile, 22 ordinary women have publicly accused Trump of sexual assault. Dr. Christine Blasey Ford volunteered her testimony in Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing, and then was forced into hiding to escape death threats. Marie Yovanovitch and Fiona Hill delivered stunning, meticulously prepared evidence in the Ukraine scandal as just, you know, part of their jobs. Most recently, former top Mike Pence aide Olivia Troye, who served on the administration’s Covid-19 task force, spoke bluntly on-camera about Trump’s blatant disinterest in fighting the virus and habit of derailing the task force’s work. That same day Dan Coats, Trump’s former National Security Advisor, wrote a New York Times op-ed recommending that Congress establish a commission to ensure that the American people trust the credibility of November’s election. For … reasons, I guess. Coats is remarkably vague about why the commission is needed, and why now. Trump’s name never comes up.

Dan Coats is 77, retired from a long career in the top echelons of the GOP. Olivia Troye is 43, a lifelong Republican who has spent most of her career working in national security. It’s safe to say she’s tanked both her career and her place in the party. Why was she willing to put it all on the line in real-time, for free, while he walked on eggshells? Why do mid-career women keep matter-of-factly sounding alarms, while powerful men sell us books or toothless warnings and call it courage? (By the way, it’s worth noting that while the recent Trump whistleblowers are white women, Black women like Cheryl Dorsey and Cathy Smith have a decades-long history of exposing wrongdoing in industries from aviation to policing to the military.)

There is the tired theory that women are just inherently better and more altruistic than men. I find it particularly irritating when men espouse this view. It sets us up as paragons of rectitude, not the complex human beings we are, and it’s awfully, well, convenient. The glass cliff phenomenon, wherein women are given corporate power when the business is already in crisis only to be blamed for failing to save it, is just one example of how the savior role tends to work out for us. We also simply don’t know a lot about how women lead outside of patriarchy; you might as well ask how we lead outside the Milky Way. But within male systems, there are clues to the whistleblower gender gap.

For example, just as it’s assumed that Mom will take the weird-looking chicken leg, at work it’s often expected that women will take on the necessary grunt work no one else wants to do, and women feed this expectation by volunteering for thankless tasks. “Never volunteer to be the note-taker in a meeting,” I used to tell the women I mentored. “Don’t always be the one who brings the report print-outs. And never join any ‘diversity committee’ that’s clearly just for show. Let a man spin his wheels on that for once.”

“It’s just hard to deliberately not be helpful,” one woman replied.

“But you are being helpful,” I said. “You’re just doing it in ways that are actually valued.” She was right, though. Particularly when you are the only woman in the room, it can feel downright insubordinate not to bite when gruntwork is dangled. Prioritizing the collective over our own interests and needs has been drilled into women so hard that it’s difficult sometimes to not just bite the bullet and do the thing we know someone has to do, especially if no one else is jumping up to offer.

And particularly in the wake of #metoo, evidence abounds that men aren’t so keen to talk about other men’s crimes. Sometimes, their silence seemed to come from a tragic struggle with the concept of subjectivity. “But he never acted that way around me,” they said, unaware that a woman’s reality might look very different. Or they kept it in the family. After Harvey Weinstein’s downfall, Brad Pitt was one of several high-profile men to say he’d known about Harvey’s ways, and had spoken very sternly to him about cutting it out, but that seems to have been as far as anyone went. The wagons were displeased, but they circled anyway. As for the men in my office, I believe they genuinely thought the executive’s past was common knowledge and if the women were fine with it, they could be too. With such high stakes, it’s not hard for me to imagine Olivia Troye deciding that if she didn’t talk, no one would.

Women whistleblowers are often lauded as courageous, with good reason. But what goes unsaid is that it’s easier in some ways to break away from a pack you were never a full member of anyway. When I think back on my years as the only woman in the room, what stands out most is my alien status, and how hard and imperfectly I tried to pass as a native, absorbing the mannerisms and language of the men around me but never quite fooling anyone. Even among the men who respected and cared about me I was inherently other, and inherently alone.

Now think of Christine Blasey Ford, watching male politicians impugn her motives on national television before her first public appearance. (Ironically, I recall one of them speculating that she was just looking for a book deal.) Think of Marie Yovanovitch, who knew that Trump and Rudy Giuliani had conspired with others to “take her out.” Think of Olivia Troye, whose former boss famously won’t dine or meet privately with a woman other than his wife. How far could she expect to get, reporting to a man who treated her as a sex trap first and a professional second? When women are kept at arm’s length from where the real decisions happen, a critical distance grows in the gap. From where we stand we can see both the inner sanctum and the world outside, and when it becomes clear that the world needs to know what’s happening in the sanctum, we simply have less to lose. I’m not sure that men understand this. Perhaps it’s better for the world if they don’t.