Our government is eager to get people back to work. And for a lot of families, that means putting economically disadvantaged kids living in pandemic hot zones in unsafe classrooms. Here’s one New Orleans teacher’s account of fighting to keep her students safe.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

By now, most schools around the country are back at work, whether virtually, in person, or somewhere in between, following a long summer of heated dialogues about how and whether it’s even safe to reopen schools while we were in the grips of a coronavirus pandemic that was infecting millions of Americans and killing hundreds of thousands. I’m a teacher and an activist in a particularly hot “hot zone”—I live in New Orleans—and together with my colleagues, I spent the months of July and August organizing to force an intractable, business-backed school board to delay in-person-learning, which had been slated to reopen to students on August 12.

Jefferson Parish, a bedroom suburb of New Orleans where I teach, is the most populous parish—or county—in Louisiana and has the largest school system, referred to as JPS. Its next-door neighbors, Orleans (where New Orleans is located) and St. Tammany Parishes had both decided by the end of July to offer 100 percent virtual learning for their public-school students until after Labor Day. Our local group, Louisiana Educators United (LEU), was grappling with how to negotiate with JPS, when they announced their determination to open in mid-August—initially, our teacher union seemed paralyzed and unable to respond.

LEU was inspired by the “Red for Ed” movement that had galvanized wildcat strikes in red states like West Virginia and Oklahoma over scandalously low teacher wages and deep cuts to teachers’ health care. The movement spread to Arizona and Los Angeles where working conditions, class size, and the lack of nurses, counselors and school librarians in large under-resourced districts were the focus. Beginning in 2018, Red for Ed groups were springing up all over the country to work both with and outside official teacher unions.

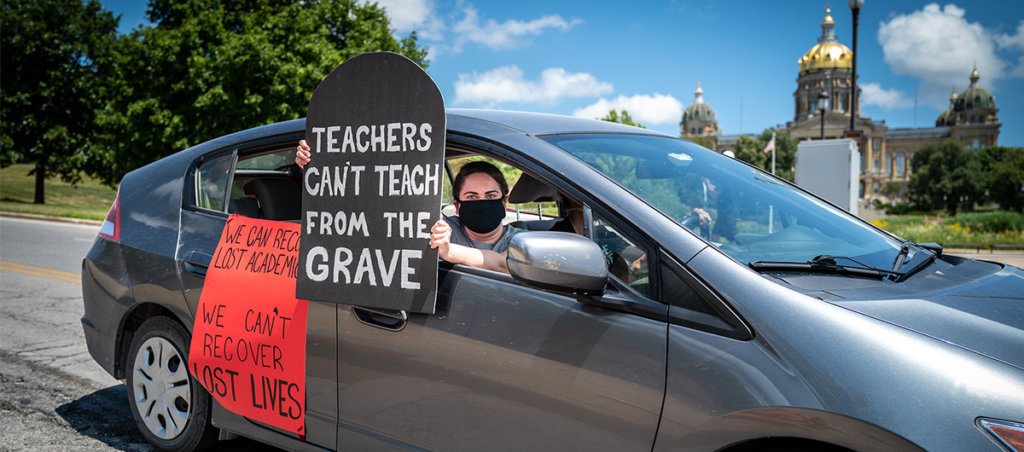

The impact of the pandemic on education has propelled teachers to take to the streets and raise our voices. Inspired by months of Black Lives Matter demonstrations, called by our belief that public health and science are being ignored in a politicized rush to reopen schools in our blood-red state, members of LEU decided to organize with or without our union.

Our first rally took place in a grassy spot outside the gates of what we call “501,” a stand-in for the address of the central office of Jefferson Parish Schools. For teachers in the system, “501” is synonymous with the endless requirements, restrictions, observations, and evaluations that have made teaching so unpleasant. In the last 20 years, wave after wave of school reform has crashed against the reality that is teaching underserved children. Teachers in Louisiana have been silent and silenced as our profession has been gutted by budget cuts, privatization efforts, and the movement to hold teachers accountable for the intractable achievement gap in school systems that serve low-income students and students of color.

We didn’t know what to expect, so we were amazed when multiple local news trucks and a growing throng of mask-wearing, sign-carrying, socially distant teachers turned up to show support and document the event. Cars drove by and honked their horns in support. Our numbers, by our own estimate around 200 people, were reinforced by our ties to other local groups working for justice, including activists from Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and Black Lives Matter.

And the reason: Teachers here are terrified of going back into our school buildings, which have been neglected for years. Basic cleaning and school supplies are in short supply during the best of times. The majority of our board members are beholden to the Jefferson Parish Chamber of Commerce who underwrite their campaigns. The business community wants schools open so that the parents of our students can get back to work at the Walmarts, Targets, and fast-food restaurants that line the sprawling corridors of Jefferson Parish. All over the country, the rhetoric at the beginning of the pandemic—that teachers were heroes, that teachers should be paid a million dollars for what we do—had abruptly shifted to admonishing teachers to quit whining and get back in the classroom.

Despite the power of our first rally, JPS wasn’t budging. Schools opened to teachers on August 3 as promised. We were all shocked by the conditions of the buildings. We had been told they were going to be deep cleaned, but they were as desolate and dirty as ever. All the recommended safeguards were unfulfilled, from biohazard containers in each room to handwashing stations to ensure socially distant and regular hand hygiene. No one was passing out hand sanitizer, sanitizing wipes, masks, or face shields. Many teachers are barely wearing their masks, and few seem to grasp the basics of social distancing and static pods.

So we kept the pressure on. The monthly board meeting was scheduled for the third-day back-to-school for teachers. We decided to hold another rally, then flood the board meeting with people willing to comment on the botched and misguided attempt to open for students on August 12. This time the rally was bigger, with better signs and costumes (this is Louisiana after all). And it took place inside the 501 gate—closer to where the monthly board meeting convenes. This time, the union, who had so far refused to join ranks, came out in force.

At the rally, I spotted one of my former Speech-class students, a brilliant young Brazilian immigrant named Martin. He was slated to speak—and I to introduce him. In our Speech class, Martin would give speeches about the power of the American dream and free-market capitalism. I knew he’d been a supporter of Trump and Bolsonaro. Although our politics couldn’t be more different, I try never to indoctrinate students in my beliefs. Instead, I engage them and challenge them to think critically.

So when one of Martin’s classmates, another student from Brazil, was detained with his father by ICE, Martin sought my help to find legal representation with pro-immigrant groups for the family. As we worked together to get Paulo and his father released, our conversations about politics grew more nuanced and complex—about Trump, about immigration, about Black Lives Matters. This past summer, Martin texted me several times from Black Lives Matter demonstrations protesting the murder of George Floyd. I was moved by his willingness to evolve, to become more politically aware and engaged in direct action. It’s why I asked him to speak at the rally.

When he took the mic, one of the first things he did was thank teachers for standing up for him and his classmates. “I’m proud of you for standing up for safety and for delaying the beginning of schools,” he said. “It’s not safe.”

Amid my pride following his speech, we lined up to go into the board meeting. The union had promised teachers they would have comment cards, but the bureaucrats at 501 refused to distribute them—and the doors were locked. As we waited to get inside, a young woman, speaking about the school board in Jefferson Parish, yelled into the microphone: “They don’t give a fuck about us!” A teacher behind me in line, sniffed, “That kind of language doesn’t help our cause!”

When they finally opened the door at 5:30 p.m., a security guard told us that they will only take comment cards until 6 pm. There’s no way the 150 or so teachers, who were outside listening to speakers, will all be able to fill out comment cards and get in the building before six. Social distancing in the boardroom was being enforced, so they have set up spill-over rooms with TVs, further limiting how many people will get to speak.

Martin and I filled out our cards and found the last two seats in the boardroom. I had to slip out to use the bathroom, where I discovered that the school board building bathrooms are all pandemic safe: touchless flushing toilets, touchless hand-washing stations, touchless soap and paper-towel dispensers. I was outraged. Good enough for them but not for the teachers, not for the students. This is what I needed to address to the board, this “tale of two spaces.”

Because once in the boardroom, I saw, too, that they had whole rows of seats blocked off, but social distancing is impossible to enforce in most classrooms as they are. The boardroom had state-of-the-art technology, while we are being asked to teach virtually, on nine-year-old laptops. The board room has three cameras, each with its own operator, to record the meeting, but teachers are being asked to instruct in-person and virtually simultaneously, wearing masks while recording themselves in real-time on those decade-old computers. In the context of the pandemic, the discrepancies between 501 and most of our school buildings seemed monstrous and cruel.

The newly appointed superintendent introduced a pediatrician from Ochsner Medical Center, a network of hospitals in Jefferson Parish, that had several deals with JPS, including a set-aside of 50 percent of seats in one of the elite charter schools for Ochsner employees and a gift of land on which to build their own school.

The pediatrician appeared to be reading from the statement released by the American Association of Pediatricians in July claiming that children do not get the virus as often or as severely as adults, nor do they seem to transmit it. Of course we now know this is not true.

One of the only two Black members of the nine-person board grilled the pediatrician about the safety of reopening schools. The pediatrician refused to state unequivocally that it will be safe for all, given the high rate of infection in Jefferson Parish. He repeatedly stated he is not an epidemiologist.

The crowd started chanting: “Answer the question!”

The second Black board member moved to delay the start of school until after Labor Day. It is seconded by the other Black board member. One of the white board members moved to refer the motion on the floor to the executive committee. The school board president seconded it. The seven white board members voted to take the amendment to the executive committee, and the board broke for executive session.

Martin and I had a socially distant huddle with another former student. Both young men asked me if I thought they would return with a decision to delay. Before I could answer, the board came back with no decision, and public comments began.

Teacher after teacher begged for more time and more training. Teachers were crying. A kindergarten teacher gave a mini-lesson, including vocabulary words, manipulatives, examples, all punctuated by the refrain, “Do our lives matter?” When her three minutes were up, they cut her mic.

One teacher revealed that she had full-blown COVID-19 in March. “I contracted the virus at the same time as my student’s mother,” she said. “I am here. She is not. You do not understand the guilt that sits on my heart and on my mind. What if I did something wrong? What if I did this?”

After hours of teacher and parent comments, with many more still to go, a recent alum of Jefferson Parish Schools approached the mic. Wearing a Malcolm X baseball cap, and a T-shirt with Malcolm X and Dr. King on it, he described how his classmates have been failed by Jefferson Schools. He talked about friends in prison. He talked about the disregard of Black learning and Black lives. He said, “I realize I’m getting a bit animated, but I’m trying to get your attention.”

He directed his comments to the board president who was bent over her phone.

“I’m talking to you now!” he yelled directly at the board president. “If you send these children back to school, and they die, it’s going to be on your hands!”

She cut his mic and the crowd started chanting, “Let him speak! Let him speak!”

Armed Jefferson Parish Sheriff officers, hovering in the back of the meeting, approached the young man, their hands on their weapons. The crowd started yelling at the JPS officers not to touch him. As he gathered his things and left the boardroom, he hollered at one of the officers, “Why are you walking towards me? You look like me!”

The crowd started chanting “Black Lives Matter!”

The board president, one of only two women on the board, began to cry. The longest-serving board member moved to adjourn the meeting. Madam president and the rest of the white members of the board scurried out of the room.

The teachers, activists, and alumni kept chanting, “Black Lives Matter!” and “Push the date back!”

My two former students and members of LEU got up out of our seats and started chanting louder. The white board members poked their heads from the executive chamber to watch in horror as their boardroom morphed into a Black Lives Matter rally. Slowly, the chanting died down and the many teachers who were still waiting for a chance to speak slowly drifted out into the night to find Jefferson Parish Sheriff cars sprinkled throughout the parking lot, and drones flying overhead surveying the rally. The white board members were escorted to their cars by the sheriff’s office, while the two Black board members, without security detail, mingled with the crowd.

My two former students asked me, “How is this possible? How can they cut off the scores of people waiting to speak? Will the motion to push back the date to begin in-person learning die now?”

It hurt to tell them that this is so often how things go. The interference by business interests large and small in our state and local school board elections has stacked boards with people who will push through school closures, charter school take-overs, and draconian policies regarding teacher evaluations tied to high-stakes standardized tests. Decades of neglect of public schools has allowed school buildings to deteriorate and the school-to-prison pipeline to flourish throughout Louisiana, the most carceral place on earth. The same lack of investment in the lives of the Black and Brown children is behind the white board members’ autocratic insistence that it was safe and fine to open schools while the numbers of positive COVID-19 infections were at 13 percent in early August. The rate of infection in Louisiana, as elsewhere, disproportionately affects Black and Brown people in staggering numbers.

All of the teachers who have come to the rally and the board meeting teach because we love our students. We want them to be the best people, the best citizens, they can be. The fact that four young people—Martin, Andrew, the young man whose mic was cut and his sister—care enough about what’s happening to be part of a rally and a school board meeting is the very thing we work for. We can’t let them down. When two days went by without any word from the board, Louisiana Educators United announced our next rally at 501. Hours before the rally was set to begin, the superintendent released a statement pushing back the date for re-opening for face-to-face learning two weeks. It was a small victory, but it was our victory.

Watch the full video of the board meeting here