So many of us underestimate our pain, because we've been socialized to believe we're making something out of nothing. But aches are often an alarm system that can save our lives.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

My ex used to call it the Big Pain. Especially during my period, especially on the first day, but also at other unpredictable times, I might be walloped by a pain so overwhelming that it was difficult to talk or stand upright; I often broke out in cold sweats, as if in shock from a physical injury. It felt like being impaled at bladder level, not just what you might call a “stabbing pain” but genuinely like being stabbed all the way through the body. (I thought often of the rod going through Phineas Gage’s eye.) If I was at home and quiet I could feel it start to come on, gulp several ibuprofen, and get horizontal, but it also struck at unluckier times: on the subway, or driving, or trying to navigate an airport, or at work. “It’s just a thing that happens,” I would creak out to concerned friends or gate agents or the coworker I called at the last minute to cover my video store shift. “It’ll pass in a couple of hours. I don’t know.”

I suspected the Big Pain was period-related, because of location and timing. But I did not consider for a moment that it might be some kind of period malfunction. Wasn’t big pain just part of the menstruation experience? I eventually asked some friends whether it was normal to have cramps so bad you couldn’t move or speak, and they all said their periods were similar. I recently reread a conversation with my ex from 2011, when I was trying to decide whether to have a serious talk with a doctor—seven years after my first Big Pain. “I mean what if it is JUST CRAMPS,” I fretted in the chat. “Then I am RIDICULOUS. ‘Oh, no, I have lower abdominal pain that happens during my period! WHAT CAN BE HAPPENING?’ It’s like going to the doctor because you suddenly discovered fingers on the end of your arm.”

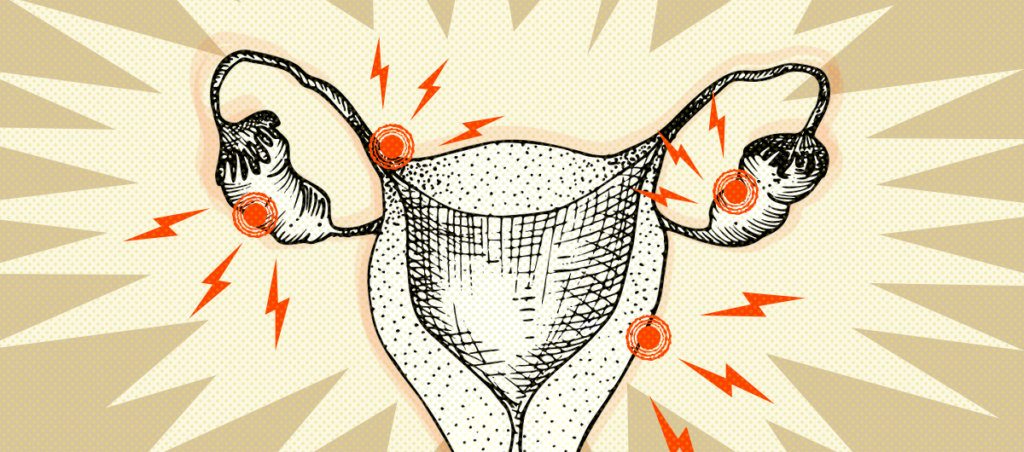

I did have cramps—but I also had endometriosis. It took me eight years to find this out. This is typical; the average time from symptoms to diagnosis is four to eleven years. And part of what slowed me down—and, I think, part of what slows people down generally—was the perception that painful periods were, if not strictly unmentionable, then certainly not worth mentioning.

It’s not that people with periods don’t talk about them. But our conversations start from the premise that they’re unpleasant, inconvenient, unfair, a burden—and specifically a shared burden, one we can therefore discuss only among ourselves. On top of this, most menstruators are women, and even more grew up being treated as if they were women at formative times—which means we’re discouraged from complaining or demanding care, especially if the complaints and demands have to do with our physical body, especially if the physical body has to do with our reproductive organs. (Even pregnant people, the subset of uterus owners about whom our society is by far the most solicitous and protective, tend to get lightly scoffed at for always needing to sit down, eat certain foods, avoid other foods, get the COVID vaccine first, and so on.) This all means that we are disinclined, for any number of reasons, to consider that our periods might be worse than normal. It seems whiny, like complaining about your period must mean you can’t handle the same pain as everyone else. It seems self-centered, like you consider your suffering fundamentally more important than others’. It seems needy, like you must be clamoring for service. And women are expected to be many things, but we are not supposed to be crybabies.

I spent years playing down the Big Pain because I didn’t want to be seen—by friends and partners, by doctors, or by myself—as deliberately playing it up. I was so scared of being diagnosed with “normal cramps and no chill” that I talked myself out of seeking treatment for years—and the people around me were trying so hard to be chill that they talked me out of it, too. But I don’t blame my friends for telling me that my experiences sounded normal. Even when I admitted to being temporarily incapacitated, I would immediately walk it back: at least it only lasted a few hours, at least it didn’t happen every month, at least my cycle was pretty long, at least I didn’t faint or throw up. (I did at one point ask a friend with endometriosis what it was like for her, entertaining a vague suspicion; when she told me she sometimes passed out, I immediately concluded that this must be a different thing. She followed up by admitting, “Some people think I’m a wuss.”) It’s also possible, of course, that the people I asked were suffering too, and didn’t know their pain warranted investigation. Endometriosis and similar disorders are common—probably even more common than we know, since we’re not talking to each other about them. If you ask someone else with a uterus whether it’s typical for cramps to flatten you, there’s a one in ten chance they’ll say “yes,” and mean it, not because you’re both normal but because you’re both unwittingly ill.

As with most health complaints that are more common in people coded as women, the indifferent, dismissive medical establishment bears some blame for all the cases that are diagnosed belatedly or not at all. I had it relatively easy as a white woman—because I’m fat, I don’t expect or generally receive humane treatment from doctors, but at least the medical establishment doesn’t literally think I don’t feel as much pain—but still, gynecologists routinely shrugged about it, probably assuming I was being a weenie about cramps. (The first time it happened, I went to the ER, where I was put in a room, given painkillers, and ignored until I eventually slunk out on my own. “I think it might be a burst ovarian cyst,” I said to the one nurse who saw me. “Sure,” she said, “maybe.”) One doctor told me that if I could come in while it was happening, perhaps he could investigate; I didn’t point out that while it was happening, I generally couldn’t get up even to fetch an Advil.

But our internalized expectations of ourselves—that we will not whine, that we will not ask for support or accommodation, that we will not make a big deal out of something other people endure with a smile, that we specifically will not make a big deal out of anything perceived as Lady Stuff—plays a role as well. People with endometriosis may face a frustrating blockade at the doctor, but we also may not make it to the doctor in the first place, because we don’t want to make a fuss. In fact, after surgery it turned out that in addition to the Big Pain I’d been powering through a host of smaller pains that I hadn’t known were symptoms. Some of them, like stomach pain, I’d gone to the doctor for previously, but when there was no obvious medical cause I’d felt ashamed of my hysteria. Most, like fatigue and bladder pain, I had thought were just what it felt like to be alive.

Even leaving aside the structural injustices in health care that keep so many of us from getting treatment for anything, we also have to struggle with gendered (and then, on top of that, racialized) reluctance to seek attention or care, or to recognize ourselves as deserving care, or even to acknowledge our symptoms as meeting some obscure threshold of meriting care. We are used to being expected to suffer in silence, and so we expect it of ourselves. But I think it’s time for less silence, and hopefully also less suffering—even if it means admitting that we feel pain.