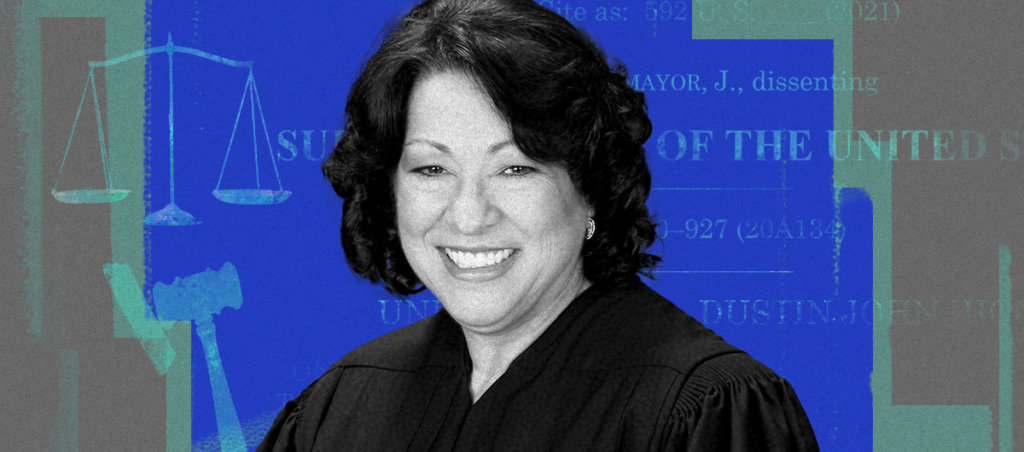

In the wake of RBG’s death and amid the Supreme Court’s dangerously rightward lurch, Justice Sonia Sotomayor has emerged as the moral compass, calling out devastatingly bad decisions and sounding a warning for what may come.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In an era where the United States Supreme Court is lurching rightward, Sonia Sotomayor keeps reminding us what justice truly is, and how much it doesn’t look like the horrors of the conservative majority on the Court. Her dissents are miniature masterpieces that are equal parts rage and thoughtfulness.

This is no new thing. While on the Court, Justice Sotomayor has always carved out a space where she shows abiding care and kindness to those society has discarded, particularly in criminal cases. However, the Trump era and the nomination of three distinctly unkind conservatives—Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—has accelerated how often Sotomayor is forced to push back against her colleagues,

Recall that at the end of 2020, as his shambolic and vicious presidency ran down, the Trump administration went on a literal killing spree. The administration had reinstated the federal death penalty in July of that year after a 17-year hiatus. Trump’s Department of Justice proceeded to make the most of the brief time in which it had to kill people, with the unvarnished cruelty of the death penalty being exacted upon 13 people from July until Trump leaving office on January 20. (In contrast, every state in the country put a total of seven people combined in all of 2020.)

It was nothing but an orgy of killing, and Justice Sotomayor didn’t hesitate to say so. When dissenting from the execution of the Trump DOJ’s final victim, Sotomayor called it what it was: a “spree of executions.” In the lame-duck period between the time he lost the election and the time he finally went away, Trump’s DOJ put three people to death. No president had executed anyone in the lame-duck timeframe in over a century, but Trump packed three in that short time.

Sotomayor also called out her conservative colleagues for their sheer eagerness to help with the killings, pointing out that the Supreme Court intervened to lift stays that lower courts had imposed, failed to provide prisoners with a meaningful opportunity to air their challenges, and very rarely offered any explanation as to why. She concluded that dissent with a stark final paragraph that began, simply: “This is not justice.”

When all three Trump appointees sided with the old-school hardliners on the Court to ignore public health in favor of caving to religious conservatives, Sotomayor called that out too. In late November 2020, as we were notching well over 150,000 new COVID cases per day, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn sued the state of New York over capacity restrictions. The conservative majority, minus Chief Justice John Roberts, happily overlooked the case spike and the COVID deaths piling up to hold that it was unfair to churches if they couldn’t hold potential super-spreader events.

Justice Sotomayor pointed out that to conclude that there was no public health risk from removing capacity restrictions on churches was quite frankly ridiculous. She noted that medical experts, rather than conservative jurists who will always rule in favor of conservative religions, had made clear that “large groups of people gathering, speaking, and singing in close proximity indoors for extended periods of time” was a major source of COVID spread.

It’s her most recent dissent, though, that taps into the sheer fury and heartbreak of what it must be like to sit on a Court that is simply so … careless. Careless about human life, careless about precedent. Just careless.

Last week, reversing a trend toward mercy that had persisted for years, the conservative majority of the Court ruled that someone who committed a crime as a juvenile could be sentenced to life without parole. It’s a decision that says that people are irredeemable, even if their offense happened when they were quite young.

In the cruelest, sickest twist, the opinion was authored by Brett Kavanaugh, a person who cried and raged and screamed during his confirmation hearings about how unfair it would be to judge him over anything he did in high school. Apparently, that only applies to rich Ivy Leaguers like Brett.

It’s not just that the most recent decision was cruel. It’s not just that it flies in the face of mercy. It’s that the decision threw out a decade of Supreme Court precedent in its zeal to lock juveniles up forever.

For years, the Court—particularly now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy—had slowly built an edifice to protect juvenile offenders. Roper v. Simmons, in 2005, saw capital punishment banned for juvenile offenders. In Graham v. Florida, back in 2010, Justice Kennedy found that a juvenile who committed a non-homicide crime could not be sentenced to life in prison without parole. There were two reasons for that. First, brain science had advanced to the point where we could determine there were “fundamental differences between juvenile and adult minds.” The court also found that juveniles were “more capable of change than are adults.” In other words, juveniles can grow and change, and with that, deserve mercy.

2012’s Miller v. Alabama saw Justice Kagan writing for the majority and finding that mandatory life without parole for juvenile offenders under 18 at the time of their crime violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments.

You might be forgiven for wondering how, particularly in light of Miller, the Court could decide that life without parole for a juvenile in this most recent case was just fine. In large part, it’s thanks to Kavanaugh’s sleight of hand.

Kavanaugh’s mercy is so small, so cramped. All a juvenile offender deserves, in his mind, is that a judge can exercise discretion—the life without parole sentence can’t be automatically imposed—and that the judge “consider” the offender’s youth. There are no requirements as to what that needs to look like. A mere passing thought about the age of the offender would be enough for Kavanaugh.

Sotomayor’s dissent is a master class in throwing the Court’s own words back at it. She reminded Kavanaugh that the “essential holding” of Miller was that a lifetime in prison is “a disproportionate sentence for all but the rarest children, those whose crimes reflect ‘irreparable corruption.’” She traces the Court’s attempts at extending mercy, in fits and starts, across Roper, Graham, Miller, and 2016’s Montgomery v. Louisiana, showing, inexorably, that precedent dictated the opposite result of what occurred here. In fact, she said that Kavanaugh’s opinion distorted past precedent “beyond recognition.”

Sotomayor zeroed in on the fact that where the Court’s past cases, to the extent they left any room for life without parole for juveniles, only did so if a judge made meaningful findings that the child was “incorrigible”—incapable of change—and that their crime was not the product of “transient immaturity.” Kavanaugh changed that to a requirement that a judge just vaguely “consider” that the offender was young.

Kavanaugh did some additional handwaving, declaring that this procedure he just invented would actually help make life without parole sentences for juveniles “relatively rare.” Sotomayor brought receipts to the fight, though, noting that in Louisiana, where life without parole for juveniles is theoretically discretionary, 57 percent of juveniles have been sentenced to precisely that in the past few years alone.

Ultimately, Sotomayor’s dissent shows that this is a Court that no longer cares for precedent. The conservative wing of the Court will do what it wants to do, precedent be damned. Or, as Sotomayor put it: “The Court is willing to overrule precedent without even acknowledging it is doing so, much less providing any special justification.”

Sotomayor didn’t just talk about the law, though. She told the story of the boy, now a man who has been in prison for half his life. Brett Jones, she wrote, killed his grandfather a mere 23 days after turning 15. He experienced extreme abuse in those 15 years, being beaten with sticks, switches, and paddles. He never received affection. In one of the cruelest, saddest details, Sotomayor writes that his stepfather rarely even called him by his name, instead calling him epithets like “little motherfucker.” He began cutting himself as young as age 11. After Jones killed his grandfather during a fight, he tried to save him with CPR.

Sotomayor also reminds us just how small Jones’s request is: All he wishes for is the chance to go before a parole board.

Though Sotomayor doesn’t come out and say it, it’s clear she understands that Brett Jones never had a chance. He certainly never had the multiple chances Brett Kavanaugh had.

In reading her dissents, It’s worth remembering that Sotomayor was attacked from the very beginning for her belief a judge’s rulings will be shaped, in part, by their background and experience, and that the law’s pretense of neutrality was just that—a pretense, a fig leaf, a lie. Remember how people mocked her statement that a “wise Latina” might reach a better conclusion than a white male who didn’t have the same lived experience? At the root of that criticism was the notion that white men make neutral decisions, while the rest of us are terrible and weak products of our biases. But Sotomayor’s background, to be frank, has made her wiser than the white men around her, particularly Kavanaugh.

Sotomayor’s dissents recall one of the most famous in the modern era. In 1994, Justice Harry Blackmun declared that he would never again vote in favor of the death penalty, despite previously having supported it:

From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death. For more than 20 years I have endeavored–indeed, I have struggled—along with a majority of this Court, to develop procedural and substantive rules that would lend more than the mere appearance of fairness to the death penalty endeavor. Rather than continue to coddle the Court’s delusion that the desired level of fairness has been achieved and the need for regulation eviscerated, I feel morally and intellectually obligated simply to concede that the death penalty experiment has failed.

Like Sotomayor, Blackmun called out his colleagues for ignoring the Court’s own precedent in its zeal to punish people:

It is not simply that this Court has allowed vague aggravating circumstances to be employed, relevant mitigating evidence to be disregarded, and vital judicial review to be blocked. The problem is that the inevitability of factual, legal, and moral error gives us a system that we know must wrongly kill some defendants, a system that fails to deliver the fair, consistent, and reliable sentences of death required by the Constitution.

On the conservative side of the court, you now have (1) death penalty fetishists; (2) people who believe juveniles deserve no mercy (except when that juvenile is attempted rape enthusiast Justice Kavanaugh, in which case it’s all just high-school high jinks!); and (3) anti-science churchophiles who believe their very soul on is compromised if they’re asked to celebrate their religion virtually. It’s a mean, small, terrifying worldview. On our side, we have Justice Sotomayor, who blazes bright with her anger and her deep, deep kindness. In spite of the losses, it’s a much, much better side to be on.