Growing up, women were fed a steady diet of mixed messages of what motherhood entailed. I discovered I needed to define what it meant for me.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

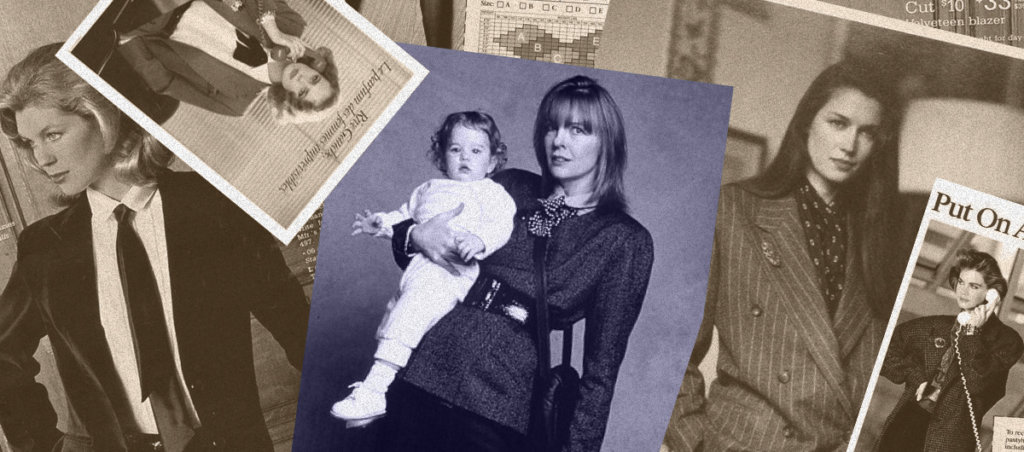

The women of Gen X were raised on a shocking number of lies and mixed messages; as with all good lies, they were supple enough to adapt to race, place, and local expectations.* Millions of girls like me were told that if we worked really hard and believed in ourselves (also really hard) we could be anything and have it all. We were told if we wore suits like men, but also not like men, or maybe not a suit at all, maybe if we added shoulder pads to our dresses to make our dresses “strong,” we could have the career of our dreams.

We were raised to aspire to that dream career and also to motherhood, expected to want motherhood as much as we wanted the career, but also to not be overtly interested in motherhood, or to ever discuss motherhood in any but specific personal settings, like with other moms, with whom we were expected to talk about nothing but being moms, a role which, it was made abundantly clear, was boring, embarrassing, subject to endless cultural mockery, and the pinnacle of any good woman’s life. Needless to say, we were also told to make ourselves attractive to, have sex with, and marry men.

What we were not told was that most of this was nonsense, made up on the fly, at best with good intentions, often with the very worst of intentions. I think our parents truly believed that all we needed was a can-do attitude and just didn’t grasp the tenacity of the patriarchy or the frequency with which American capitalism would fail over the coming decades. “It all,” as a life goal, is perhaps understandable but really only serves people with something to sell, whether shoulder pads or political ideas. A lot of us weren’t “like me” — white, middle-class, or possessed of even notional access to “it all.”* A lot of us didn’t like men. And the whole being a mother thing? A veritable motherlode of lies and mixed messages!

In this, as in so much else, American culture has not advanced as far as we want to believe. Mothers are still underpaid, overstretched, dismissed, and belittled, told to sacrifice work for family and family for work, expected to love our children beyond all measure and also not talk about them too much, or (God forbid) allow our bodies to look like we produced them. In the pandemic’s early days, I had what turned out to be fever dreams that all those adorable videos of kids Zoom-bombing their parents’ workdays would force Americans to acknowledge that the parental/professional divide had always been a myth. Instead, women were just forced to leave their professions. Having it all, indeed.

In the course of my life I’ve tried, to the best of my tender abilities, to refuse almost all of these constructs. (Though I will acknowledge that I did wear a lot of shoulder pads.) It took me a while to grok that hard work might not be sufficient to achieve one’s dreams, but I got there in the end. I liked boys but always knew that a man’s boner was not the sum total of my worth. And I outright rejected the notion that motherhood was a requirement of my gender.

In a culture rooted in and built on misogyny, it serves those in power to tell you that motherhood is both a woman’s highest calling and not up to her. Both parts of that are a lie.

The act of reproducing is a biological function that has no inherent moral value or bearing on your worth as a human. Full stop. And where patriarchal arguments don’t hold sway, it can be a choice. I chose differently with my first pregnancy.

The guy who provided the sperm that time wound up marrying me, and we eventually chose parenthood together. And I did, in fact, love both of my babies beyond all measure, with a kind of intensity that was bracing from the first moments of their lives.

I refused to act as if they were a secret, best not mentioned in job interviews or planning meetings, because all that is also a misogynistic lie. I insisted I had a place not just at the mom table, but at the academic table, the professional table, the table of rock and roll and Star Trek fandom. I insisted, in fact, that no matter what we heard in every corner of American society, being “a mom” had never been distinct from any of those things. I wrote endlessly about the support that parents of all genders need but are routinely denied, and also about women’s God-given right to refuse motherhood altogether.

There’s a good argument to be made that all this brave truth-telling achieved nothing beyond losing me work and at least one dream job. Foregrounding my children definitely cost me the chance to address a United Nations conference in Tokyo, not to mention any knock-on effects from having addressed a United Nations conference in Tokyo, none of which I can presently imagine because I wasn’t there. And it turns out that missing one international conference when you’re a woman renders you invisible.

I should be mad. I am mad. I am and will probably die mad about all the things I lost because the patriarchy didn’t fold when I stood up to it.

But I would do it all again.

I am many things, and despite my professional frustrations, have accomplished much. My children are not my accomplishments. They are their own glorious accomplishments, two of the finest people I’ve ever met, and excellent long-term roommates to boot.

But one just graduated from college, the other from high school. The space one or both of them has shared with their besotted parents for so many years is about to grow incomprehensibly large and lose a very great deal of its charm.

When they were 18 months and just past four, a copy of Newsweek landed on my doorstep (a lot has changed since the aughts) and in it, woman of letters Anna Quindlen’s regular column. That week she wrote of the challenges her generation of women had faced, balancing the same roles I was then learning to balance. “In the kitchen is a magnet,” she wrote, “that says mom is not my real name.”

Change happens slowly. Boomers had also been taught that women must be mothers, and that professional women with both children and an ounce of self-respect must simultaneously deny motherhood as their identity.

But Quindlen’s youngest was set to leave home, and after a Quindlen-esque journey through truths and discoveries, her last sentence reduced me to helpless weeping, my own, very little kids on either side of me: “Three rooms empty, full of the ghosts of my very best self. Mom is my real name. It is, it is.”

One day, in third grade, my daughter failed spectacularly in her school’s spelling bee. Weeks of study and she was out on the first word. This was shocking, and I stood up in the audience to let her run into my arms, holding her tight so no one could see her little face. We escaped to a stairwell where I kept my arms around her through the worst of the heartbreak. Eventually she went back to her classroom, and I walked home to finish whatever piece of writing I was on deadline for. I don’t know if I hit the deadline.

Naming is a powerful and frankly political act. I married the love of my life but rejected his last name because I already had one; I had to fight to get it back once when a government office incorrectly changed mine to his and wouldn’t acknowledge the error. I have never been willing to be who other people tell me to be.

I think about that spelling bee all the time, about holding my eight-year-old, knowing I couldn’t fix anything. As she and her big brother cycle through their endings and beginnings, as they seek the names they will claim for themselves, I reject the lies I was told one more time and stake a claim as political as it is personal: Though only two people may use it, my real name is Mom. It is, it is.

[*Editor’s Note: The original version of this column appeared with language that was unintentionally exclusive. The author has requested edits in these two passages. We regret the oversight.]