Women are expected to minimize our trauma and love our scars. Ten years after the writer suffered a hit-and-run accident that took her ear, she realized she didn't have to embrace expectation.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

On July 26, a personal milestone will quietly pass while I’m preoccupied by my 4-year-old, who rapidly fires off complex questions: Who made the world? How big is the last number? What do you call a group of whales? His baby brother, a year and a half now, will be pulling on the fridge whining for snacks, wandering around the house crooning Cock-a-doodle-doo, and performing a crocodile death roll each time I change his diaper.

The date will mark ten years since the day an accident changed my life. Well, it did and it didn’t.

Change is a loaded word. Very little did seem to change. The accident did not alter the course of my life or lead me to a profound new calling. Instead it rerouted me for a while, added an urgent need to find a therapist, and transformed the way I saw myself, and how I thought about beauty.

On July 26, 2011 I was struck in a hit-and-run while crossing the street on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. I had exited the subway and waited to step into the street until the walk signal blinked white. What I recall is a black wave crashing toward me. I awoke in a sticky pool of blood and felt the hot, hard pavement against my body. My hair seemed to be everywhere. The memory is an instant, maybe less than a second, in which I try to push myself up off the road. Then it’s the chaos of the ambulance, another instant, and questions I couldn’t quite find the words to answer.

Anniversaries of traumatic events feel useless, a harsh light cast on our emotional and physical scars, but with no common rituals like flowers or cards or parties or balloons to mark the occasion. Each year the date passes and maybe my sister will text me or my mom’s voice will break as she retells the story. It’s become family folklore. Sometimes when we’re all together and there’s wine and food and laughter, the event snakes its way into the conversation. Everyone shares their version: where they were, who called who, how fast they drove. My mom plead-screaming into the phone when she finally got someone on the line at the trauma center. I live two hours away, somebody needs to tell me if my daughter is dead. I remind myself that while I was whirling in and out of post-concussion consciousness, my loved ones were mobilizing, panicking and enduring their own trauma.

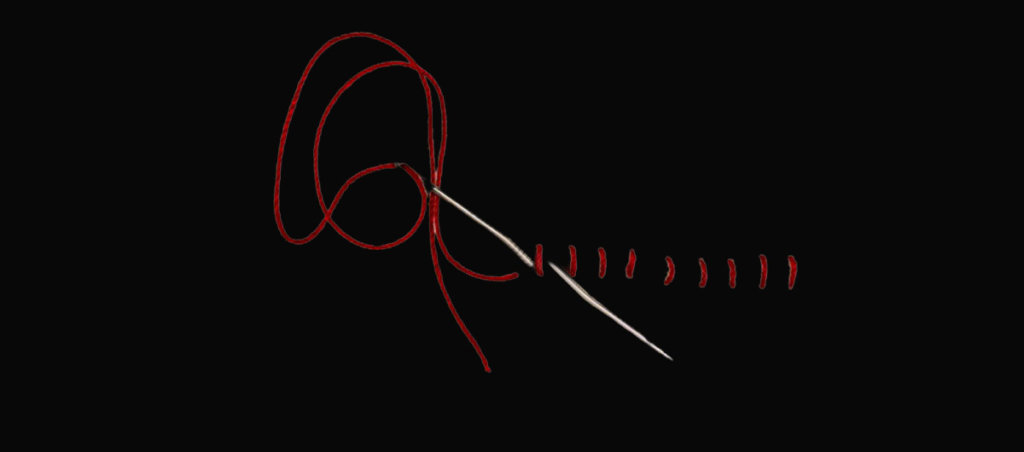

I suffered a concussion, facial lacerations, and the loss of my left ear, which was ripped almost completely from my head. It took a Park Avenue doctor two years and four surgeries to create my reconstructed ear—or something close to an ear—molded from my ribcage and skin grafted from various parts of my body. I called myself a patchwork, took earless selfies, and giggled as sunglasses drooped down my face. I instinctively tried to tuck my hair behind an ear that wasn’t there. Each day I plaited a braid over my left shoulder. I was certain that if anyone could see my deformity they would know my secret: I was broken. A quiet rage simmered inside of me.

For months at a time I went back to my normal life and then another surgery would sneak up and I would rest at home in my apartment while my loved ones cared for me. There’s some nostalgia for this time, for the tenderness with which I was treated, for the periodic respite I was given to recover from yet another surgery that was meant to bring me closer to “normal.” But there was no more normal for me. There was anger for this stupid, meaningless injury. There was anger for the driver that hit me and sped away as I bled alone in the street. There was anger that I didn’t get to speak at the hearing where the driver was sentenced to probation. There was anger that I was forever marked, left with scars and an ear that was ugly and painful. The anger prompted the guilt. I was alive. I was lucky. My therapist wanted to hand me tissues and make sad faces when I cried. I wanted her to yell at me, tell me to toughen up, remind me to be grateful.

It took marriage and motherhood and an entire decade to realize that I have a right to my emotions. I don’t have to be over it, put it behind me, move on. I can be grateful and angry. These feelings can coexist. The stories women share around trauma are too often ripe with clichés: She’s such a fighter. I’m grateful to be alive. We’re not supposed to tell you that we’re also angry or that we feel ugly. We’re supposed to move forward and minimize our trauma; Others have been through much worse.

Ten years later, I have tenderness for that girl in her mid-20s who tried to deal with her trauma by naming it anything else. I have two small children now, so my needs and my vanity are not always at the forefront of my awareness, but I was recently standing in my bedroom wearing only a towel when my reflection caught my eye. I positioned myself between two mirrored closet doors so that I could see the back of my reconstructed ear. It was throbbing in pain that day, and I was feeling frustrated. I stared in the mirror and I cried. I let the tears roll down my face and I let myself sit with the anguish. I hate it, I whispered to no one, I just hate it. Ten years later I know it’s okay to feel that pain.

Learning to acknowledge and honor my feelings—the messy mix of anger and sadness and gratitude—has helped shape the way I speak to my kids. One day I was leaning over my son’s car seat to buckle him in. I felt his little hand wrap around my ear, and I froze. Because the ear is made of cartilage, it is hard like bone, and it hurts my head if someone grabs it. “What’s this?” He asked, and I had to fight the urge to brush it off, to turn it into a lesson about safely crossing the street. It’s my ear, baby, the one the doctor made me. Remember? He paused. Oh. Did it hurt? I told him that it did hurt and that it still does, and I delicately removed his hand from my head and kissed his little fingers.

I can respond to his questions honestly and admit when I don’t know the answers. I don’t deny my emotions, even if they’re ugly. I don’t blame myself. It would be easy to warn my son that a similar fate awaits him if he doesn’t look both ways when he crosses the street, but I did everything right, and I still ended up face down on the pavement. I don’t have to make sense of everything that happens.

The court hearings ended long ago, and this year no one is sending me flowers, but I am marking the anniversary by giving myself permission to feel both the loss and the luck and the weight of the experience. I am giving myself permission to complain when my ear hurts, or talk about how ugly I feel. I don’t have to minimize my trauma. These scars are mine forever, and I will wear them honestly.