The author of the timely new book, ‘Cultish,’ breaks down the strange gender dynamics of cults and explains why women appear to be drawn in more often than men.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

“Are women more likely to join cults?”

I was in the midst of a Zoom interview to promote Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, my new nonfiction book examining the language of “cults” from Scientology to SoulCycle, when this podcaster’s question hit me like a frisbee to the temple. “There sure are a lot of women in the book,” the host, a 30-something new mom, remarked. My impulse was to explain that there aren’t actually more female sources in my book, it only appears that way because men enjoy default status in our culture, whereas women and nonbinary folks are considered “other”; thus, she distortedly perceived an overrepresentation of women. (Studies have found that when women extras make up more than 17 percent of crowd scenes in movies, audiences mistake the cast as looking predominantly female.) When it comes to the big screen, books, or any other public setting, we’re just used to seeing more men.

Over the two years I spent compiling sources for Cultish, I was careful to interview former cult members from a wide range of social backgrounds. But the podcast interviewer inspired me to look back at the gender dynamics of those who actually made the cut, and I discovered she was right: They were indeed mostly women. That may very well speak to my bias favoring women’s stories, but once the question was posed—“Are women more likely to join cults?”—I couldn’t get it out of my head.

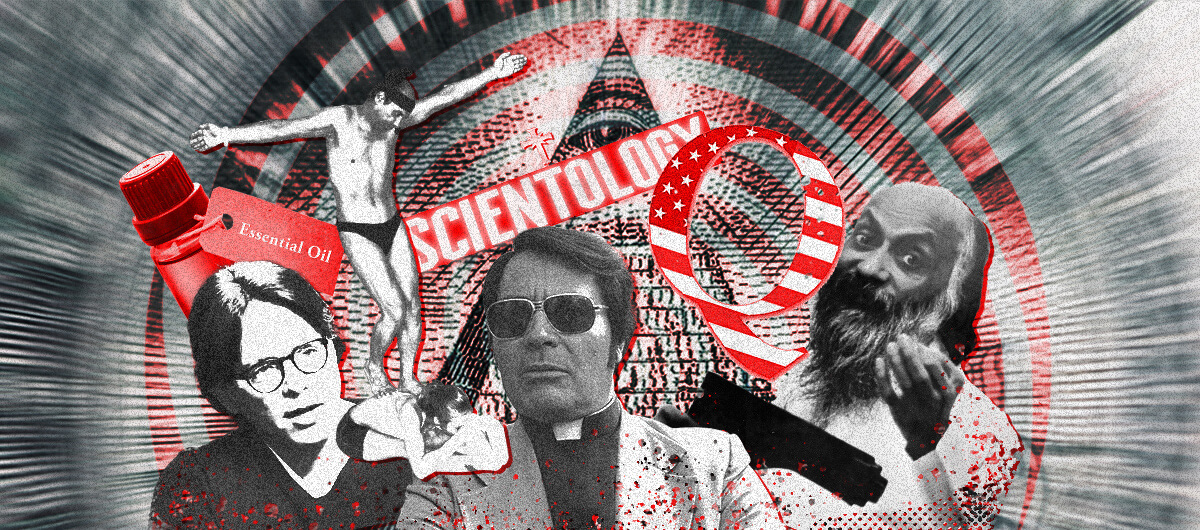

It is actually a trickier question than it might initially sound, the answer requiring more nuance than just Googling the demographics of groups like Heaven’s Gate, Rajneeshpuram, Love Has Won, or NXIVM. This is in part because the answer depends on how we define “cult” in the first place, which, as I learned during my research, doesn’t objectively exist. We tend to think of “cults” as intrinsically sinister. But scholars have never been able to agree on one singular list of criteria that distinguishes a “cult” from a “religion” from any other kind of tight-knit, ideologically bound group.

You can name certain red flags—isolation, deception, charismatic leaders, an us vs. them dichotomy, financial and physical exploitation, supernatural beliefs, shattering exit costs, etc.—but not every “cult” will check every box; meanwhile, you’ll find all kinds of mainstream organizations, from Silicon Valley start-ups to health trends to established religions, that do: check, check, check.

Many experts I spoke to when I was researching Cultish actually avoid using the “cult” label altogether (at least in formal writings) because it has become so subjective and sensational that it’s not even useful to identify what potential power abuses are at hand. The word “cult” has become a pejorative shorthand term, used to trash socio-spiritual groups that society doesn’t approve of. Consider that many of today’s religions, from Catholics to Baptists, were once regarded as such in the U.S. A cult’s perceived legitimacy is based on cultural norms, no matter whether its tenets are any stranger or more dangerous than a group we have come to accept. Why, for example, is Catholicism accepted but, say, Scientology isn’t? What makes one weirder than the other? I often return to this famous religious studies joke: “cult + time = religion.”

That said, some data has been collected on whether women or men are more likely to believe in certain “culty” ideas. For example, it has been noted that women more than men are attracted to New Age beliefs (like “manifestation” and the power of the mind to heal disease), while more men than women take a liking to conspiracy theories. In his 1997 book Why People Believe Weird Things, science writer and historian Michael Shermer wrote, “If you attend any meeting of creationists, Holocaust ‘revisionists,’ or UFOlogists … you will find almost no women at all (the few that I see at such conferences are the spouses of attending members and, for the most part, they look bored out of their skulls).”

Since 1997, the demographics of conspiracy theorists has shifted, however: These believers don’t just assemble in tiny, testosterone-filled conference rooms anymore—they gather online. A chaotic combination of social turbulence, social-media algorithms, and the COVID-19 pandemic, has unearthed the conspiratorial seeker in so many folks that might not fit the stereotype. Picture New Age yogis and “vaccine-risk-aware” mothers, who’ve had their trust in the government, mainstream media, and Big Pharma shaken, who have been encouraged to “do their own research” (a.k.a. fall down a rabbit hole of confirmation-biased internet searches that offer convenient fantasy answers to modern life’s most confounding questions like, “Is the pandemic real?” and “How do I keep my children safe?”). It seemed an unlikely crossover, at first: that of paranoid, mostly male right-wingers and bohemian-looking female hippie types. But America’s modern tumult has ushered so many “progressive”-seeming American women to an anti-government, media-averse, doctor place-way place. Over the past ten years (and especially over the past 18 months), we’ve seen the rise of conspirituality—a portmanteau of “conspiracy theory” and “spirituality”—which marries the woo-woo notion that we’re on the precipice of a “paradigm shift in consciousness” with the classic conspiracy philosophy that a sinister group is covertly controlling the socio-political order.

As the boundaries between the conspiratorial and the New Age blur, so does the gender breakdown. Anti-vaxxers and Plandemic truthers would fall squarely into this category of “conspirituality,” but so would plenty of less conspicuously QAnon-related wellness buffs: the sorts who might enlist in an essential oils multi-level marketing company, for instance, or wear a “Namaslay” racerback to their whitewashed yoga class, or run a “holistic self-care” Instagram page. The sorts who maybe searched for “natural immune-boosting remedies” one day and wound up in “all doctors are brainwashed” conspirituality territory, unable to pilot their way to the other side of the algorithm.

Nowadays, I’ve found that the word “cult” can apply to basically anything from a fringe-y church to a group of online radicals to a fitness company (e.g., Peloton), a popular beauty brand (e.g., Goop), or health craze (e.g., celery juice). Over the years, as our sites of connection and meaning have shifted due to phenomena like social media, globalization, withdrawal from traditional religion, and government mistrust, we’ve seen the rise of all kinds of alternative subgroups—some destructive, some less so. This is why I find it helpful not to categorize groups as a “cult” or “not a cult,” but instead being placed along a “cultish spectrum.”

In general, Pew Research data suggests that women around the world tend to be somewhat more religious than men. In Britain, specifically, studies show that women attend church in higher numbers (though, as it happens, men outnumber women in other U.K. places of worship). If you consider multi-level marketing organizations—the predatory, legally loopholed close cousin of pyramid schemes—along the cultish spectrum (I do), then certainly women are more likely to get involved, since these groups have purposefully targeted unemployed, suburban wives and mothers since the dawn of the modern direct-sales industry. I tend to think of MLMs as cultish, mostly for their ability to usurp so much of their members’ lives: after all, these “communities” are missionary in character; they’re helmed by charismatic leaders who are worshipped on the level of a religious leader; and they foster intense, co-dependent relationships between recruits, which can make defecting feel almost impossible. They love-bomb enlistees with promises of female empowerment, while pressuring them to snip those who speak ill of the business out of their lives, only to gaslight them into blaming themselves when the system inevitably fails.

If you look at some of history’s most notorious cults (i.e., the ones that make the news), you will indeed find groups boasting a lopsided quantity of female members. Consider all the young women followers of Brazil’s Inri Cristo, who claims (common story) to be an incarnation of Jesus. The majority of folks who perished in the Jonestown massacre of 1978 were Black women.

I think the more interesting question, however, is this: Why do women seek alternative sites of spirituality, community, and opportunity? And why is that power so often abused? From there, an even more consequential line of questioning might be: What do the demographics of power abuse in our culture look like in general? And what can women do to protect themselves?

All kinds of theories have been tossed around explaining why women have proven more vulnerable to groups like NXIVM and the Peoples Temple, led by Jim Jones (a.k.a. Jonestown). These range from “women are conditioned and/or wired to believe there is something wrong with them” and are thus more allured by “self-correction” narratives to “physiological or hormonal differences” to women’s “long history of oppression.”

My theory, after having studied and interviewed women and men from groups all across the cultish spectrum, has less to do with women’s historical subjugation and more with their idealism and resilience in the face of it.

Let’s look at Jonestown: Black women lost their lives in disproportionate numbers on that tragic day in 1978, but it was not because their oppression made them easier to hoodwink. Black women in the 1970s were the targets of a complicated political tempest, and found it impossibly challenging to amplify their voices amid those of the white, often inhospitable, second-wave feminist activists, as well as the civil rights movement’s mostly male leaders. But they weren’t willing to give up, especially not after meeting Jim Jones, a passionate young preacher who had ties to all the “right” people (i.e., Angela Davis, the Black Panthers, the American Indian Movement, the reactionary Nation of Islam, many left-leaning Black pastors in San Francisco, not to mention his own non-white adopted children). Jones gave the convincing impression that he’d help get these women’s voices heard. As feminist scholar Sikivu Hutchinson, author of White Nights, Black Paradise, explains, “Black women were especially vulnerable because of their history of sexist/racist exploitation, as well as their long tradition of spearheading social justice activism in the church.” So many of these women died in Jonestown not because they were “desperate” and thus more susceptible to “brainwashing,” or because they were insecure and seeking self-improvement, but instead because they had so much to gain from a movement that turned out to be a lie. Optimistically, they were willing to hold out all the way to the end because that’s how they badly wanted to realize the “Promised Land” they were so vehemently guaranteed.

Now, let’s scrutinize the gender, race, and power dynamics of Jonestown more closely: While the overall population of the settlement was about three-quarters Black, Jones’s inner circle was almost entirely composed of young white women. This is a pattern of cultish power abuse: The Peoples Temple, the Manson Family, NXIVM, Bikram Yoga are just some examples where an older man presides at the top, and is perceived as all-powerful. Just below him are a tier of fair-skinned young women who exchange their sexuality and whiteness for slightly more authority (or the illusion of such). At the bottom lies everyone else.

This power structure is by no means exclusive to “cults”; it’s the structure of most major corporations, mainstream churches, and patriarchy in general. “Which, to me, has always underscored how non-radical many of these communities actually are,” comments Koa Beck, author of White Feminism. “It’s often just misogyny without electricity.”

There are exceptions, of course: It’s not hard to think of female leaders at various points along the cultish spectrum (closer to Goop and Gwyneth Paltrow than NXIVM and Keith Raniere), from the controversial online spiritual guide Teal Swan all the way to “cult-followed” entrepreneurial gurus like Rachel Hollis. But you’ll notice that these women—who are white, slim, normatively beautiful, and who make no effort to approximate male authority—are not aiming for a level of political or prophetic power as high as Jim Jones; they’re going for a softer, maternal sort of “cult” leadership. They’re seeking exactly the type of cultish power deemed acceptable for a traditionally feminine, porcelain-skinned white woman—no more, no less. And to that extent, people follow them.

It seems the gender dynamics of “cults” will continue to mirror those of our culture’s power structures at large until the patriarchy is smashed once for all. As we continue to fight for a more gender-equal society, it’s up to us to stay vigilant to the potentially ill intentions of cultish leaders, from self-help schemers conducting NXIVM-esque conferences in the Catskills to metaphysical mental-health swamis ballyhooing self-serving quackery on Instagram. In the meantime, if women can find ways to better support one another, fulfilling those needs for connection and purpose that we so badly crave, stepping up when called for (and stepping back when called for) such that no one ever holds too much power for too long, then perhaps we can take all the best parts of being in a “cult” and leave the rest behind. Maybe that’s overly optimistic thinking. Or maybe it’s just the amount of optimism we need.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.