First Person

The Western Way of Life Isn’t Climate Conscious

How one writer found a sustainable way of life beyond American borders

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

The grandmas where I come from, they’re always talking about the way it was back in their day. They’d rinse out plastic bags and hang them on the balcony clothing lines for their next trip to the market. I still see them in grocery shops with their reusable bags. They’re the last to pay the 10 cents for the paper alternative in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

When my family and I moved from Bosnia to Palm Desert, California in the early ’90s, the old ways were lost to the new ones—and fast. We lived in one of the hottest climates on the planet, and yet our dryer was still an essential component of our household chores. We could line our clothing racks on balconies and backyards year-round, our European relatives would tell us, the ones who had to wait for spring to again enjoy the scent of sun-dried laundry.

I was ignorant to the old ways as a kid. By nature, we weren’t producing heaps of waste during the first years in America because we still stuck to traditions my mother and father knew from our culture, Bosnian culture. We also penny-pinched that way, eating all the food until the fridge was emptied, sharing one car among our little refugee family of four, cooking mainly from scratch. In the beginning, there were no microwaves, no packaged foods, no running to the gas station for soda bottles and unnecessary trips to wherever for whatever.

But things shifted over the years. Convenience entered through the back door. We, too, fell for the trap of easy. First came the cars for each of us, then the TVs in every room, then the incessant heating and cooling of the home. I didn’t question it until my later years, once I was already out of the house and waking up to the world through the mouths of passionate professors, who didn’t sugar coat it when they told us our ways were fraudulent, that we were indeed responsible for the downward direction our planet was headed. Waking up to realizations about my own role in the climate crisis through my daily choices was jolting.

I made small changes. I switched over to reusable bottles, refused plastic cutlery, gave up meat (periodically), went for the green labels in the grocery store. I came home on the weekends and scolded my parents for their packaged meals which made their now-Americanized lives easier. I was fully “eco” in theory, but my practice was poor. I was less an activist and more a part of an idea that I wasn’t fully rooted in. I had this great desire to be a part of social and environmental change, an important one, but my comforts were hard to abandon. I loved shopping, consuming. I hated looking at the origins of clothing labels. I wanted açaí bowls and my own car and air conditioning.

But the old ways stuck with me somehow. I was captivated by my father’s stories of simpler times back in our hometown of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. How little they had, how much that felt like. When I first visited as an adult, I got a taste of that world, of feeling like everything around you is all you have. Not imports and exports galore, but eggs with feathers still stuck to the shell and jars of red pepper paste delivered by the man who makes it. It felt like time-traveling back 20 years in Bosnia. Things were smaller, closer, more real. Things that seemed to be a niche in the U.S.—which had been preached as a more ecological way of living—were done out of necessity in Bosnia. Discounted vegetables were always lying in the front of the market so they wouldn’t be wasted. Air-conditioning systems were forfeited for blazing hot summers devoted to sundresses and hand-fans. Electricity prices varied throughout the day, encouraging the public to consume less. Walking was a reliable and a time-worthy means of transportation.

I liked it, this opportunity to form a life around a set of values that seemed already ingrained in a culture. I felt like this change I’d been so eager to make in the U.S., with my co-op memberships and my strict grocery store routines and my refusal to touch single-use plastics, was somehow already built into the way of life in Bosnia.

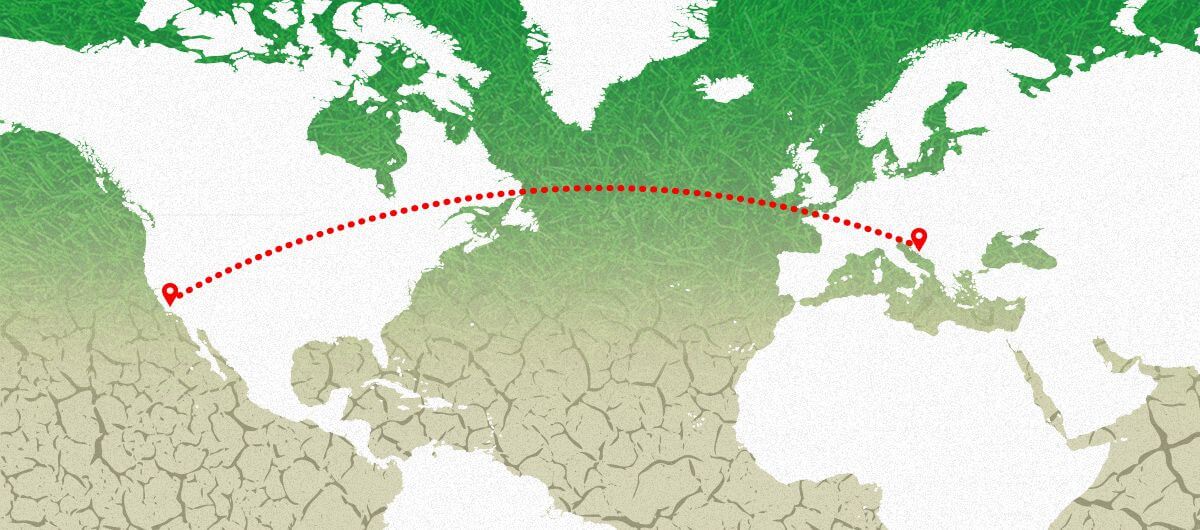

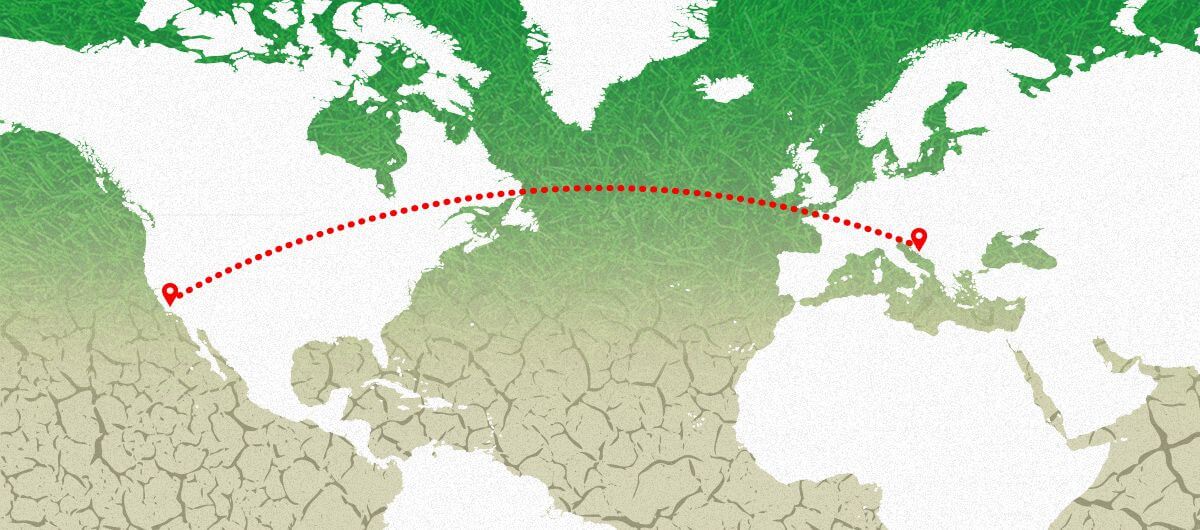

When I finally moved back to Bosnia, my Americanized ways were dismantled, but not without a fight. Being in Bosnia allowed me to make the personal changes I’d always wanted to make, but that seemed impossible in the United States. I moved onto a bare piece of land. With the help of my partner, I began growing my own food. My means of transportation is solely by bus or bike. Most of my transactions are done in cash, locally. I needed certain conditions around me to release me from the burden of choice we as consumers feel daily, specifically in the West. And those choices aren’t just about what type of milk we want with our coffee, but what type of person we consider ourselves to be in this rapidly, alarmingly shifting climate.

But the ability to move myself somewhere where it seems in some way easier to make these choices, a privilege. Because the truth of the matter is, those hardest hit by the climate crisis won’t have the luxury of choice. Those of us who can choose have the responsibility to work with our environment to mitigate the effects of a warming planet. We need communities to band together in moving toward clean electricity and food production and supporting the policies which seek to bring us there.

For those of us who genuinely want to do better, the weight of this responsibility often is overwhelming. Yet personal action only does so much. Just 100 investors and state-owned companies are responsible for around 70 percent of the world’s total global greenhouse gas emissions, according to Harvard Political Review. As climatologist Micheal Mann noted, “a fixation on voluntary action alone takes the pressure off of the push for governmental policies to hold corporate polluters accountable,” USA Today. And yet, our commitment to our behavior, specifically those of us with the privilege to enact change on a political level, has the opportunity to strengthen our own willingness to hold major corporations accountable. That, and we still have reason to believe that it is our daily choices that affect the market which we push and pull with every consumer decision we make. It’s a dance between the personal and the political—to live like our behaviors have an impact but to continue to organize collectively against the corporations that try to turn the blame on individual responsibility.

Changing environments helped me step back enough to see the wave of immense pressure I felt to solve our world’s climate problems, while also revealing how the environment I lived in was shaped in such a way that made it extremely difficult to be the eco-being I wanted to be. It’s not to say all the tools weren’t there for me to take responsibility for my own actions, but rather, it wasn’t making it easier for me to make better choices. The environment in which I lived wasn’t shaped in such a way that I was able to easily take bus rides to work, to limit my food selection to seasonal choices, and to consume less in general. In fact, it felt like I was constantly being directed toward another way—a quicker, easier way of living. And in slowing down, I was able to take notice of how the speed of the life I was living contributed to the speed of my own consumption, and the speed at which things were moving toward disaster.

Again, it’s not a choice all of us can make, it’s a privileged one which I had agency over. Some might argue it’s best to stay where we are, to do the work there. I would say that it’s about going to the places you feel connected to, places that make you feel at home and connected to the planet. That’s where authentic change can begin, regardless of where that pinpoint on the map marks us.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.