Hurricane Ida showed New Yorkers that the billion-dollar investments in flood protection after Hurricane Sandy aren’t enough to protect NYC’s most vulnerable communities.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

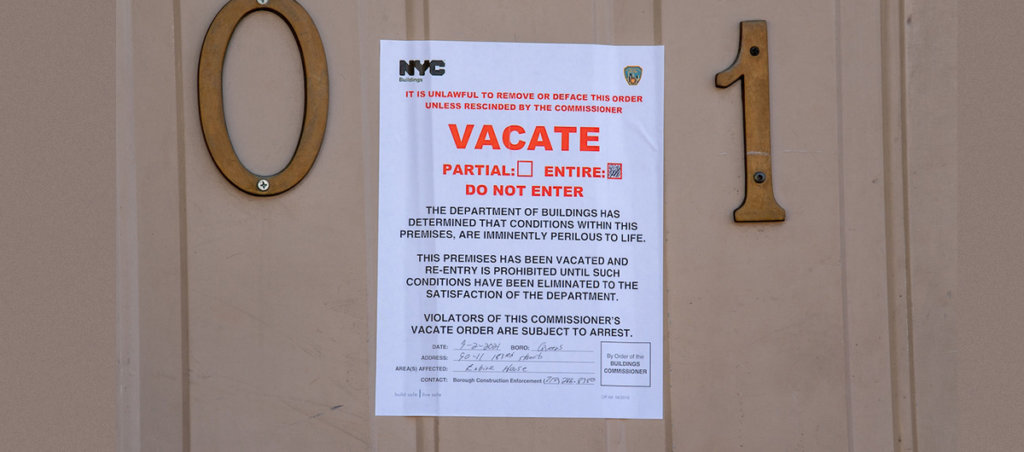

Water demands a place to flow. In New York City, a place deemed a “concrete jungle,” however, rivers, wetlands, oceans, and other natural movement paths are unsurprisingly scarce. So when Hurricane Ida unleashed seven inches of rain in just a few hours over the city on September 1, stormwater rushed down streets, gushed onto subway platforms, pooled in Yankee Stadium, sunken highways, and basements—ultimately taking the lives of 13 people, 11 of whom died trapped in their own homes.

“It was absolute carnage,” said Anthony Rogers-Wright, the director of environmental justice at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest.

It’s not uncommon for this kind of pluvial flooding to disrupt life in urban areas like New York City. But none of the preparations city and state officials implemented ahead of the storm did much to soften Ida’s blow. The storm dumped more water in a short period of time than authorities estimated in their extreme flood reports and maps. Even the billion-dollar investments in flood protection after Hurricane Sandy ravaged the city nine years ago weren’t enough preparation. The old sewer system was just too overwhelmed to take in so much water. But unlike Hurricane Sandy, which overwhelmed places near open water like Lower Manhattan and the Rockaway Peninsula, Hurricane Ida showed that inland communities are at risk of flooding, too. Both, however, disproportionately devastated the city’s most vulnerable communities: its poor, its people of color, and its immigrants.

The brunt of the storm was felt in places like Hollis, Woodside, Elmhurst, and Flushing in Queens — one of the most diverse boroughs in the city and home to many immigrants. Of the 13 people who lost their lives during the storm, 11 were Queens residents in historically yellow or redlined areas that have seen less infrastructure investment than other notably wealthier and whiter parts of the city. Many, particularly those living in Southeast Queens, can attest to years of flooding and drainage issues only made worse by a delay or lack of infrastructure investment. While New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has made the most substantial and sustained pledge to address these issues, its efforts are no match for the pace and effects of a warming planet. Hurricane Ida is yet another extreme weather event, an omen of a rapidly accelerating climate crisis, the likes of which are bound to become more frequent, according to the National Climate Assessment. And New York’s roads, sewer systems, and buildings are buckling under the pressure.

“We need to prepare for everything,” said Amy Chester, managing director of Rebuild By Design, a nonprofit group born out of the federal effort launched after Sandy. “We need to make sure that we’re rebuilding our infrastructure and our communities in a way that [they] can bounce back.”

Karen Imas, vice president of programs at the Waterfront Alliance, a coalition of more than 1,100 organizations working toward resiliency and equitable access to the region’s waterways and shoreline, is equally concerned. “We have 20th-century infrastructure and architecture in place to deal with 21st-century storms,” she said.

For those active in the resiliency and climate justice space like Imas, it has become clear that New York’s entire urban design—steeped in a history of racist policies and decades of disinvestment—needs to be rethought if the city has a chance at effectively and equitably tackling the climate crisis.

Currently, 1.3 million New Yorkers live within or directly adjacent to the floodplain, a number that could rise to 2.2 million by the end of the century. More than half of those people identify as non-white. And in a pattern typical for many metropolitan areas in the United States, those living in formerly yellow or red-lined areas—many of whom are people of color—face a higher risk of flooding than those living in formerly green or blue-lined areas. This color-coded categorization dates back to 1934, when the then-newly formed Federal Housing Administration (FHA), banks, and other institutions relied on “residential security maps” to decide which neighborhoods made secure investments and which should be restricted for mortgages. These maps were entirely based on residents’ race or ethnicity, and present one of the clearest examples of institutionalized racism in U.S. history. “Green” neighborhoods were highly desirable, up-and-coming, and explicitly homogenous, meaning white. “Blue” neighborhoods were still desirable and stable due to the low risk of “infiltration” by non-white groups. “Yellow” neighborhoods were seen as “declining” and “risky” since they bordered majority-Black areas or were prone to “infiltration” of immigrants. Finally, “red” neighborhoods were areas where so-called “infiltration” had already occurred. Almost all of them were populated by Black residents and were ineligible for FHA backing. In New York, the total home value at risk of flooding for formerly green or blue-lined areas is $4.9 billion. For formerly yellow or red-lined areas, it’s almost four times that amount at $17.5 billion.

“These were intentional policies done by city planners and government,” said Rogers-Wright. “The history of urban planning in New York, and in this whole country, unfortunately, is directly aligned with the history of white supremacy and racism.”

For Lonnie Portis, the environmental policy and advocacy coordinator at We Act—a community-based organization advocating for environmental justice — it all comes down to one word: disinvestment. He notes that systemic factors have continuously exposed majority-Black and Brown neighborhoods to severe flood risk, and officials have failed to appropriately update and maintain their infrastructure.

“No one cared about where Black, Brown, people of color, or poor individuals lived,” said Portis. “And whoever lived [in those neighborhoods] was seen as undeserving.”

The compound effect of disparities in development and decades of disinvestment is a pattern that became even clearer after Hurricane Ida. With coastal and inland communities now at severe risk of flooding, Frank Avila-Goldman, an affordable housing, resiliency, and environmental justice advocate living in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, hopes that the devastating deluge serves as a wake-up call.

“You don’t have to be on the waterfront to be vulnerable anymore,” he said. “In a way, that might bring about additional advocacy so that people realize that we have real infrastructure problems in this city that need to be properly funded if we’re going to adapt to climate change.”

Advocates and experts say that addressing the aftermath of Hurricane Ida would need to involve massive federally backed and funded efforts on part of the city and state authorities. Among other things, this means updating all parts of New York’s derelict combined sewer system, which is essentially a single pipe that carries both stormwater runoff and sewage from buildings to a treatment plant, and one that is easily overwhelmed during storms and flash floods. Another priority is the city’s century-old subway system. Even though the Metropolitan Transportation Authority invested $2.6 billion after Hurricane Sandy to fortify its resilience, cascading waterfalls of rainwater during Hurricane Ida, which shut down all lines and particularly damaged tracks in Queens, proved that there’s still much more to be done.

While these large-scale, multi-billion dollar projects will be essential to make New York more resilient ahead of the next storm, Portis, Chester, and Imas agree that reconfiguring existing systems and adding new green infrastructure to the city’s built environment is equally important.

“Nature in New York is considered a ‘nice to have’ not a ‘must have’ in many respects,” said Imas. “Now we’re seeing the implications of the lack of green infrastructure. This is not to say that the city and the state haven’t made strides over the past few years with things like rain gardens, bio swells, roof gardens, and areas that can provide this sponge effect. But it seems like this is just the tip of the iceberg.”

It’s not that the path forward is unclear. In fact, since Hurricane Ida, Rebuild By Design has compiled an anthology of ideas in the form of essays from experts in water management, data, transportation, parks and open space, regional planning, and emergency planning that explain various ways to make New York more resilient against extreme weather events. According to Chester, the obstacles are a system of governance and regulations that move much too slow compared to the quickening pace of climate change.

“What Hurricane Ida showed us is that there’s still a belief that we don’t have the answers when we do,” said Chester. “We’ve been talking about it for years, but not everyone is listening. We haven’t transformed our government, governance, and budgetary processes the way we need to transform them to actually make the impact for the answers we know we have.”

For Rogers-Wright, the extensive changes needed to adequately respond to the aftermath of Hurricane Ida have to highlight the intersectionality of the climate crisis, or as he calls it: “the crisis of interlinked crises like economic injustice, housing injustice, racial injustice, and gender injustice.”

Portis echoes this sentiment.

“There’s economic will, there’s social will, and there’s political will to do these things,” he said. “It just needs to happen and it needs to be done in a thoughtful way with particular environmental justice communities in mind, with their contribution.”

The city seems willing to do the work. There’s been significant movement on the legislative front as earlier this month, New York City Council passed Intro. 1620, legislation that will mandate the creation of a citywide climate adaptation plan. Starting in September 2022, relevant authorities will create a report every 10 years that “considers and evaluates various climate hazards impacting the city and its shorelines.” Portis said that this is some of the most comprehensive legislation put forth by the government that acknowledges the variety of environmental hazards threatening New Yorkers and the need to pay particular attention to environmental justice groups. Rogers-Wright is optimistic yet cautious; aware that policy is only as effective as its implementation.

Protecting New Yorkers from future extreme weather events won’t be easy. But Imas sees it as an opportunity rather than an obstacle. “Right now, during the COVID-19 recovery phase, there are so many challenges for the city,” she said. “But we can’t lose sight of the fact that climate is going to stay with us and continue to be a risk. The same communities that were hit hardest by COVID-19 are going to be hit hardest by storms, floods, heat. At the same time, many are in need of jobs. So there’s an opportunity here that’s not just a climate resiliency opportunity, but a green jobs opportunity. We can make this a part of the country’s economic recovery, tie it to infrastructure, and most importantly safeguard communities most at risk.”