The writer reflects on how to grieve and most faithfully honor the life and work of L.A.-based artist and activist Diviana Ingravallo, who emerged during the AIDS pandemic and died an indirect casualty of COVID, rendered invisible by legacy media.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

These past two years have felt like loss upon loss upon loss. While the numbing collective grief over the almost 800,000 Americans taken by the pandemic has blunted some of the personal devastation, the August death of Los Angeles–based artist Diviana Ingravallo still hits me with the severity of a gut punch.

Diviana, a fierce glamour-queer artist and activist from Mola di Bari, Italy, emerged in the American alternative art scene in the early 1990s, just as the American LGBT community was accelerating its rage and anguish over the AIDS crisis as a potent political and cultural force. Diviana was a contemporary of queer femme/female artists galvanized during the overlap of the ACT-UP/AIDS, Queer Nation, and the sex-positive feminist movement, artists like Michelle Tea, Annie Sprinkle, Mx. Justin Vivian Bond, Vaginal Davis, Pamela Sneed, Penny Arcade, Michele Handelman, Julie Tolentino, and Catherine Opie. A performance artist, author, and playwright, Diviana’s work was ruled by the anger, lust, transgression and quest for justice, and the venues in which she performed—New York City’s PS 122, San Francisco’s Theater Rhinoceros, and L.A.’s Highways—showcased the work of a burgeoning queer counter-culture that managed to bring together activists, drag queens, sex workers, club kids, and underground artists working in every genre.

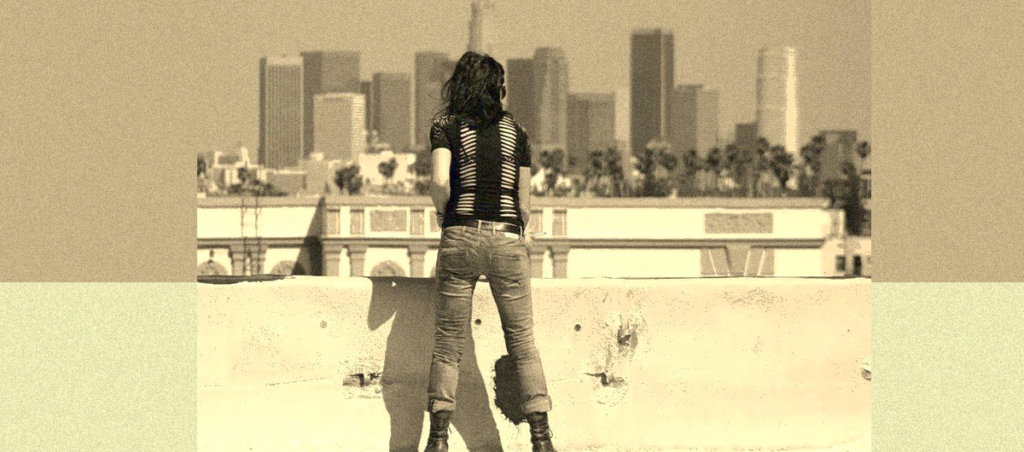

I’d performed in her San Francisco shows several times; I also edited and published her short fiction, and, over the years, we shared kind words and kisses in whichever city we overlapped. As a presence, she had all the fire of a Leo goddess: beauty mark. Red lips curled in a snarl. Her hair, endless box-dyed onyx waves. In joy, her laugh was frequent and unhinged. Fury and beauty were her propulsive forces, with a dash of irresistible madness.

Through her plays like Naked Women and Criminal Lovers, she chronicled the femme fire walk and its maddening contradictions: As feminine-presenting queers, we could easily command attention but not respect; we could be granted the power of desirability, but not the gravitas of intellectual credibility, we were often milked for inspiration and titillation but then summarily discarded, left to then rinse from ourselves the bitterness from the realization that the misogyny that chased so many of us from the straight world still followed us around what we’d hoped would be queer sanctuary, the filmy residue from the cheap trick of it all. Female archetypes dotted her narratives, particularly Biblical women. Her relationship to the Catholicism of her youth was fraught, bridling against Christianity’s patriarchal structure and homophobia, yet the iconography of the faith—the Madonna, the pieta, the flaming sacred heart—seeped into her work in words and images.

Diviana did not die of COVID, but I count her among the countless oblique COVID casualties—in lockdown, she couldn’t perform her day job as a sought-after massage therapist, and even if she could have, her body wouldn’t let her. A recent back surgery caused her incapacitating pain in her arms and neck. Income dried up. Medical care became less accessible, and forget mental-health care. A once-prolific artist who had performed around the world, her output lagged. Long struggling in a country that gives precisely zero fucks about supporting its creative class in times of strain, when Diviana was found in her bed, dead from an overdose of methamphetamine laced with fentanyl, the letters “DNR” (short for “Do Not Resuscitate”) were spray-painted in silver on her bedroom door. She had just turned 60.

With COVID shutting down all but necessary travel, and social gatherings put off, many funerals and memorials have been truncated, postponed indefinitely, or reimagined. I knew my Christian mourning standbys: In the absence of a funeral or memorial for Diviana, I could pray. I could journal. I could go to church. But as I thought of Diviana, who had the strega bellisima magnetism of Lydia Lunch crossed with iconic Italian actress Anna Magnani, I found myself yearning to honor her with something witchier.

Let this fiery woman be remembered by fire itself.

“Better to light a candle than to curse the darkness” goes the old saying, which has been attributed to everyone from Confucius to Eleanor Roosevelt. “Grief delayed is hard,” said my friend Reverend Jes Kast, a pastor at Faith United Church of Christ in State College. “So candles are a way to begin that process even if we can’t gather in person yet.” At Ritualist, an inclusive, woman-owned magic shop in New Paltz, New York, I examined the spell candles. Slender beeswax tapers. Oil and herb-infused pillars. Ritualist’s owner, Dana Cooper, bright and elegant like her carefully curated store, approved my selections of a white beeswax spell candle and four autumn-toned smaller candles called chimes, meant for single use. I wondered if I belonged in this dedicated witches’ space, but Dana assured me that candle work, really, isn’t tied to any specific religion or spiritual practice, and that one needn’t rise to some eldritch bar to use the tools. Could a Christian believer—even a wayward soul like me—do a candle ritual? I thought of Catholic churches, their rows of glowing votives lit with balsam sticks, then remembered what Jes said to me conspiratorially, “Honey, I need some stuff witchier than just Jesus, too.”

The Wicca Book of Candle Spells: The Ultimate Guide to Practicising Wiccan Candle Magic with Spells says, “All you need is a candle if you want to cast a spell. It is similar to how one would wish something while blowing out the candles on their birthday cake. The only main difference is that while you hope for something when you are blowing out your birthday cake candles, you need to assert a declaring authority whilst casting a candle spell.”

What spell did I wish to cast? I didn’t want to summon Diviana; a visitation wasn’t the goal. What I wanted was for her to know how much she is loved. How much she is missed. And maybe, if it wasn’t too much trouble, to have her give me just the teensiest little sign that she’s out there somewhere. A feather floating by. The sound of footsteps. Whatever. Nothing fancy.

American history brims with mourning rituals, from hair work—jewelry and art fashioned from the hair of the deceased and Victorian memorial portraiture of the dead, to the more recent custom of roadside descansos to people engaging reality TV mediums who claim to converse with the departed. I reached back in time beyond that and built a prayer altar—a Catholic-influenced pastiche that echoed Diviana’s sensibility of iconic subversion. A portable last rites kit purchased at a flea market with a chalk statue of the pieta. A photo of Divi that I took at our friend’s wedding. Acorns and pinecones for fruitfulness, and an apple, for Eve and all the knowledge she dared acquire. I ground some spices with my mortar and pestle, passed on to me by a downsizing queer friend. Soon the room filled with the aroma of cinnamon and clove.

There was genuine comfort in the gathering and assembly. I tucked in a hunk of smoky quartz, said to have properties of protection and deflecting bad energy, just in case, and flipped a random tarot card from my deck: Death. Number 13—a perfect bit of otherworldly showmanship for a Leo like Diviana. Wary of white-girl spiritual dabbling, I wondered if this slapdash ritual was appropriate, or, in any way, good enough. “There is a reason why Jesus took ordinary things like bread and wine, why wouldn’t our spices or acorns or leaves be blessed, too?” said Reverend Kast.

I lit the candles, then sat and stared at the flames while “My Immortal” by Evanescence played, the wailing guitar solo opening my heart to tears that wouldn’t come. I felt alternately sad and fraudulent. I didn’t lack seriousness or reverence, rather, in the empty-tank reality that is desperate sorrow, I could only do my best to honor someone I’d lost and it felt insufficient. Though Diviana didn’t have HIV or COVID, there was a cruel irony to her emerging as an artist during one pandemic, and dying during the other. The grief in my circle of friends was a callback to an earlier time when we were reminded just how disposable we were (and still are), our pain lost in a sea of indifference, if not outright hostility. The searing memory of swarms of people who believed our suffering was a form of justice. Her work, and the work of other artists that flourished against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis, gave us a language when we had no words to evoke our complicated lives. A new aesthetic and vocabulary was emerging—political, irreverent, by turns pranky and profane—and she was there, to lend shape. And now, her death underscored the ways America betrays the artistic class, the self-employed—how they get no hand up when they’re down. The conditions of Diviana’s demise are their own damning artist’s statement.

I realized I couldn’t cry because I was so angry. As the guitar wept on and candle wax ran in runnels to the tabletop like the tracks of tears I could not call forth, I gave myself permission to grieve imperfectly.

News of Diviana’s passing slipped by in the news, as if mainstream media decided that, like so many female artists, she wasn’t important enough to memorialize. Sexism and misogyny, alas, follow us into the grave, as exhibited by the paucity of obituaries about women. “Over the entire 167-year history of the New York Times,” said the newspaper, “between 15 and 20 percent of our obituary subjects have been women — a frustratingly imprecise number that also fails to fully reflect huge changes over the decades in the obituary form itself.” Queer women are represented even less, shoring up institutional hierarchies by reminding us, in absentia, who is—and isn’t—worth remembering writ large.

So memorialization falls to those who knew and cherished both Diviana and her work. My ritual for her contained the solemnity of this awareness, because I knew that with her death, we not only lost our friend and whatever art she might have produced, we also experienced a secondary AIDS crisis loss—so many of our friends and loved ones passed on in shocking speed and numbers back then, and now we’re losing the witnesses who held the story of the specific horror of that time.

Diviana was preceded in death by a great love, Tim, a faunlike gay man who succumbed to complications from AIDS in the 1990s. Queer kids understood the fungibility of the concept of “family,” and the fluid boundaries of love—some of us weren’t here to slot ourselves into the LBGT categories so much as redraw them entirely. The gatekeeping and internicine bitching in the queer community made Diviana increasingly incensed. If nothing else, Diviana was an agitator for expansion, for liberation over rigidity. A furiously bright light.

Photographer and community organizer Susan Forrest filmed her walk through Diviana’s Hollywood apartment building—the Villa Elaine, where legendary surrealist photographer Man Ray once lived—and as she navigated the long hallway to Diviana’s front door, still sealed with the coroner’s sticker, golden orbs of light bobbed in the frame, though the angle of the California sun wasn’t such that the glowing dots could be attributed to lens flare. When I saw them, I thought, “Maybe Divi is that light.” The idea seemed corny, improbable yet also very true.

I looked out at the small fountain in my backyard one afternoon and saw a male and female cardinal jockeying in the plume of water, which hadn’t happened before, or since. They batted each other playfully, shook droplets from their feathers, then alighted together, never to be seen again. It is said that cardinals—their song and their presence, represent a visitation of a loved one from the other side.

If I were to believe my prayer for a sign was answered, it was in the sight of the orbs and the two joyful, quarrelsome lovebirds acting up before my eyes. We look for signs not so much because we are certain such inter-dimensional communication is possible. We look for signs because it’s all we have.

In the face of uncertainty, it behooves us to make a friend of mystery, as paradoxically, it is the possibilities contained in the unknowable that help us make sense of the reality of loss. Does a glimpse of birds connect you to the person on the other side? Possibly. Does the sight of candle glow connect you to the meaning of their life, and yours, on this Earth? Certainly. Episcopal priest Liz Edman, author of Queer Virtue: What LGBTQ People Know About Life and Love and How It Can Revitalize Christianity says, “Our relationships with folks who have died is part of a larger web of relationship. So sending them energy, remembering them, holding them in your heart, striking a match and kindling a small flame—it’s a way of touching that energetic space where they live, ‘a great cloud of witnesses,’ who are connected with us, and connected with the transcendent.”

As much as I had wanted a sign from Diviana, Veronica Varlow, author of the craft book Bohemian Magick: Witchcraft and Secret Spells to Electrify Your Life, told me that I, in my way, was sending a sign to her, too. “My Grandma Helen,” Varlow says, “taught me that candles are a way to send thoughts, wishes or messages to the Spirits looking after us, or loved ones on the Otherside. The belief of my Bohemian ancestors and Spectaculus Witchcraft is that as the candle burns down on this earthly plane, it starts to ‘appear’ on the Otherside for your loved one to receive. Once the candle has disappeared completely on this side, it is burning brightly and whole for your loved one on the Otherside. Just like the spirit of our loved one is still there, even if we can’t see it with our own eyes, the spirit of the candle and its beautiful intention live on the Otherside for all time. In fact, my Grandma Helen referred to the Afterlife as her City of Candles.” This description brought such peace to my heart, thinking that Diviana may be out there receiving the candle I burned down in this plane, wholly formed and glowing in the city of the next.

We do what we’re able to honor those who have left us, and hold space for the anguish of those left behind. We hear redemption in a keening guitar and find comfort in a dash of cinnamon. We make visions of the mundane. Is the mystical significance of such things real? At all? I’m inclined to say yes, but I say so knowing that even confirmation bias can be a form of comfort. What I’m certain of is that grief is real. It deserves our attention, our tending, and our respect.

Better to light a candle than to curse the darkness. In Diviana’s honor, I do both.

May the flame of sacred remembrance burn its rage in our souls.