There is ample footage of the January 6th Insurrection. But as we mark the first anniversary of one of the worst attacks on our democracy, we're fighting over how to document the truth of an event witnessed by the world.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

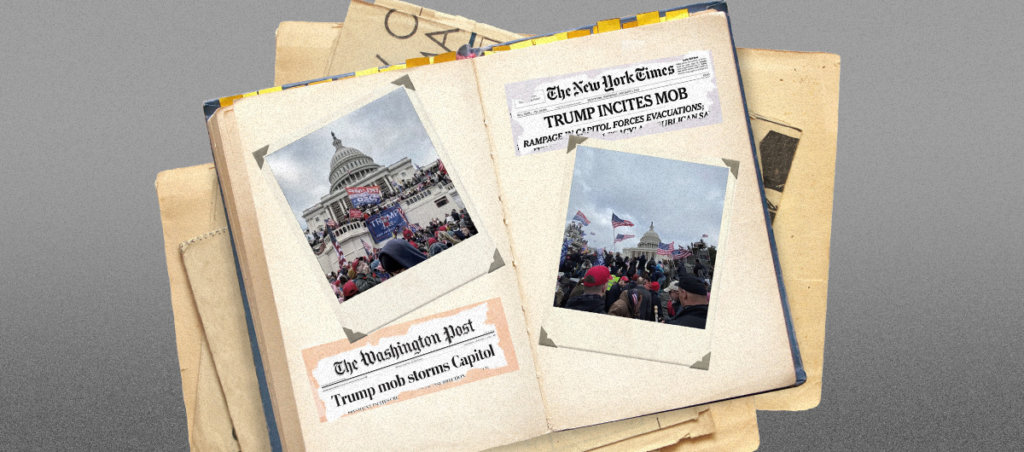

It has been nearly a year since the United States survived a coup. That was the moment the world watched our government under siege, heard the violent mob echo cries of “stop the steal,” saw the strewn and broken wreckage of the Capitol in their wake. And yet, despite all of the evidence, despite all that we know, the anniversary of the January 6th Insurrection is an uncomfortable reminder that we are a nation at war with memory.

For months, a day recorded on a thousand cameras, broadcast around the country and the globe, has been subjected to a relentless campaign of disinformation and distortion to remove the stain of guilt and muddle efforts at accountability. Now, regardless of the incontrovertible truth of fact, image, audio, or even lived experience, the commemoration of it will happen in alternate universes: one of solemn condemnation, and the other as a tantrum of victimization. There will be dueling press conferences, conflicting recollections, sharply divergent narratives about who was responsible and what it cost us. Such is the process of making a new American fable.

From our independence to our Constitution, from the Three-Fifths Compromise to the 13th Amendment, the United States has been obsessed with turning memory into myth. The January 6th Insurrection is merely the latest iteration of our uniquely American insistence that fiction is easier to swallow than fact and thus must be superior. We have spent decades demanding unbroken legacies: wise and generous founders; an enduring commitment to freedom; peaceful transfers of power. Acknowledging that these are somewhere between multifaceted truths and outright lies might complicate the story or sow unnecessary confusion, and so leaves the American mind untrained in nuance. There is no good and bad in the history of the United States; there is only good and better.

The consequence is a nation so saturated with lies that we are incapable of processing truth. At best, we watch people indulge in self-soothing denial, insisting that this is not “who we are” and that whatever scant traces of inequity remain, neither they nor their ancestors are implicated in the cause. At worst, we see the incompatibility between reality and myth explode into a frothing rage, inchoate and unrelenting, seeking revenge for the mere suggestion of complexity. The two fuel and reinforce each other, with the denial permitting and consecrating the anger, and the anger festering and growing from mere mythology into a vicious conspiracy, until it is too brutal to look at directly.

We have been led by the handmaidens of American exceptionalism—fury and denial—to a political culture where banning books is called freedom and teaching uncomfortable truths is treated like a crime. This is the machine at work at school board meetings and across social media, on cable news and in local markets, demanding a 1776 Commission to purify the country of the 1619 Project. We are no longer in conflict about the meaning of facts, but about the validity of facts themselves. Build an identity around a lie, and it will break a life; build a country atop a lie, and it will break apart.

This tiresome and infinite debate over the truth of our history comes at the cost of its purpose. We are a nation still wrapped in stories with protagonists and conclusions, wedded to notions that either doom or glory define the American experiment. Yet the yelling and conflict obscure that we have become so disconnected from our own history—that is, the facts of the past—that we are entirely unable to recognize it as the product of choice.

History is not an inevitable arc or a morally just narrator; it is not an innocuous series of greatest hits to confirm our outsized sense of superiority. It is a multitude of decisions, made by both the prominent and invisible, to shape their present with whatever tools were at hand. It was the work of a movement to add amendments for the direct election of Senators and the imposition of income taxes. It was collective action that gave life to Jim Crow, and collective action that killed it. We didn’t receive social insurance programs as a gift; these policies were designed, lobbied for, and implemented by people who were willing to move the world to make it happen. We are agents of history, every moment we are alive, and to deny this truth of our past and present, to rage at it, is to abandon the future.

And so, the insurrection on January 6th has become just another thing that happened to us, another story subjected to the whims of opinion. The upcoming anniversary of the worst attack on our government in 150 years is not a call to arms, or a defiant rebuke to the forces that incited it, but a rallying point to launch another, potentially fatal blow to representative democracy. We have made ourselves helpless in the face of it, insisting that history is her own scribe, judging without bias, rather than acknowledging the work of making a future where we are the victors who write the conclusions.

The history of now is in our hands. We can either accept that we are the product of mistakes and corrections, that we rest atop atrocities and triumphs, that we can only be exceptional as a nation as the choices we present to ourselves—or we can become a myth.

History calls us to remember—and act.