White Lady Nonsense

Can White People Reckon With Their Racist Families?

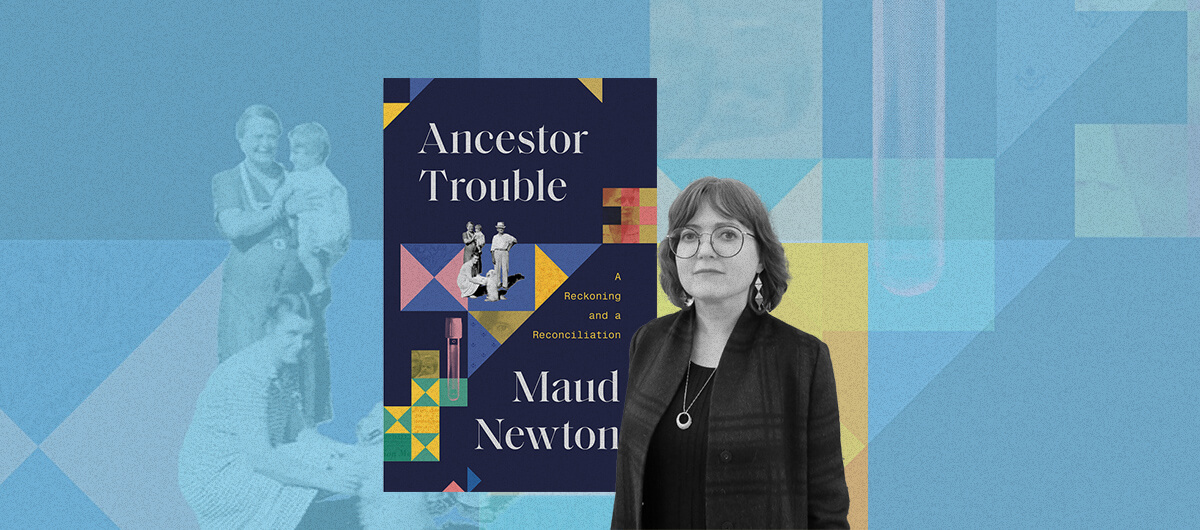

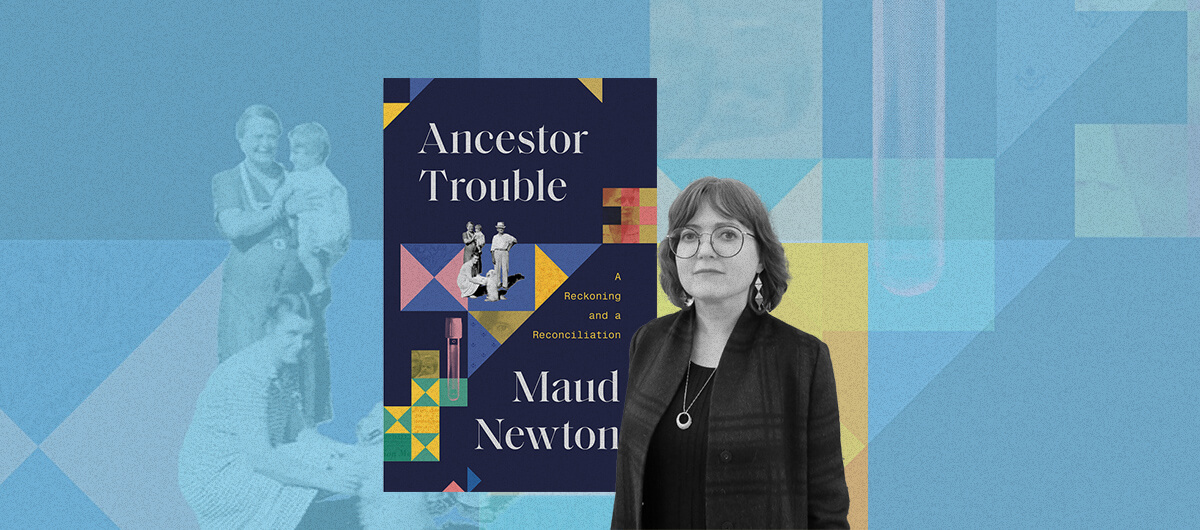

Our columnist and author Maud Newton speak with candor about her excellent new book 'Ancestor Trouble,' the brutal discovery of being a descendent of slave owners, and the question of reconciling with a bigoted parent.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Growing up in Miami, with kin scattered across Texas and the Mississippi Delta, writer and critic Maud Newton felt the pull of trying to find out who, exactly, her ancestors were. More than that, she wants to know how those ancestors continue to shape her life in the present. Raised by a racist white father, and a white mother she believed was “not racist,” Newton wanted to know where these people came from and how to reckon with a familial past rooted in white supremacy. Aided, and sometimes hindered, by the big-tech DNA platforms and genealogical firms, Newton wrote a blog in the early 2000s that explored some of the issues as she toiled at a day job. In 2014, Newton’s fascination with her own genealogy fueled a magazine article she published in Harper’s magazine about America’s ancestry craze. And now, after more than ten years of research, Newton has written Ancestor Trouble: A Reckoning and A Reconciliation (Penguin Random House, 2022), her backward-through-time search for answers about family stories that are told in echoes and half-truths.

Given my own problematic ancestry, which includes my Klan granddaddy, I was especially eager to talk with Maud Newton about Ancestor Trouble. Newton and I have lots of shared experiences and there is much about her book that resonates with my own struggles with my family history. Newton spoke with me earlier this month.

JD: Toward the end of the book, you write, “It’s one thing to acknowledge bigotry and inhumanity where we expect it, where we’ve always judged it in people we already viewed critically. It’s another thing to face and acknowledge it in the people we love most.” I just thought this was such a profound insight, one that is really hard and painful to reckon with when it comes to our own families. How did you know you were ready to delve into this work?

MN: So I know that you’ve also talked a lot about your ancestors’ involvement and a lot of the harms at the foundation of this country, so you know something about having an overt white supremacist for a father. I had a really extreme white supremacist father who was also emotionally abusive to me so I didn’t really have the, I’ll go ahead and call it a luxury, that a lot of white people have, of choosing to ignore these histories and their families. My father was very explicitly in favor of slavery, and he felt that it would have continued if it hadn’t been for what he called bleeding-heart liberals from the North. And he believed slavery was a good institution, so this is what he was trying to raise me to believe. Luckily I was growing up in Miami, and that was not the vibe of Miami in the 1970s and ’80s, although there was certainly plenty of racism there. My mom also was not [down with his racism], although she didn’t really challenge him because he was so tyrannical, and for other reasons that I came to realize later. When I started researching my family, I had expected to find at least one person on his side who enslaved people [or at least one person on his side who was an enslaver]. I found so many people who enslaved Black people. It was a shock, even for someone like me, to see how many individual ancestors of mine had participated in this. But, I didn’t expect to find this history on my mother’s side.

JD: Yes, you have a chapter entitled “Not Racist,” that takes on this subject.

MN: That was really such a gut punch when I found that because without realizing it, I had aligned myself with her as the “not racist” side or the not-fundamentally-racist side, whatever sorts of things we tell ourselves. So finding that my ancestors through her had not only enslaved people, but sued each other over who had the right to enslave these people, that was really, really difficult, but important because I realized: Oh, I’m doing that thing that I judge other people for doing. You know, I judge other people for not wanting to face these histories. And here I’m ignoring the parts where my grandmother would say racist things and I would kind of excuse them as not fundamentally who she was. So I think, on the one hand, I was always a little smug at times about my willingness to reckon with this. But then I realized, I’m actually doing exactly the same thing.

JD: Yes, I wanted to talk about one of the incidents that you ask your mother about because it’s about something that was true in my life as well, which is that my parents forbade me from watching Sesame Street, which was an inclusive, expressly anti-racist show. You wrote that your father had spanked you for watching that show, and later asked your mom whether she agreed with your father’s stance.

MN: I have a very distinct memory of loving Sesame Street. When I was 2 or 3 years old, my father discovered that I was watching Sesame Street, and he freaked out and said I wasn’t allowed to watch it, but my mother sometimes let me watch it. Anyway, you can see even in that situation, that she’s letting me do it, but she’s not directly challenging him. That ties into another event related to my father. He would [often] tell this story about a Black boy who was the son of his grandmother’s housekeeper, they lived in the Mississippi Delta. My father said the young boy stole a quarter from him, and this was his sort of example story that he would tell me and my siblings over and over again to make the point that Black people couldn’t be trusted. Even at the time, I honestly felt way more compassion for the housekeeper’s son than for my father, which doesn’t really speak to my lack of racism so much as my tough relationship with my father when I was a kid. But this was his go-to example that he would always give about why Black people weren’t trustworthy. So, a few years ago I mentioned this story to my mother, and she said it was all a lie. And, of course, looking back it was obviously a lie. But I was floored that she allowed him to tell us this story over and over again knowing that it was a lie. So I asked her, why did you let him do this? And she said, Oh, I didn’t think that you would go along with his racism. She never really offered any further explanation.

JD: There’s a passage in the book where you referenced the work of Stephanie Jones-Rogers’s They Were Her Property and you write, “In my ancestors’ wills human beings were bequeathed to wives and children alongside money, land tools and beds.” What was that discovery like?

MN: I have found a number of ancestors who were women who enslaved people after their husbands’ deaths and [Jones-Rogers’s] scholarship is so important to all of it. I wasn’t surprised so much as looking for context. In my very own family, I can see these situations where the husband is the legal enslaver of human beings he puts a provision in his will, then in the next census, it’s the wife or the daughter and her now-husband who are now the enslavers. I think because of the way my family is, I never really assumed that women weren’t involved [in slavery].

JD: One of the big pushbacks that I often get on my work is that I don’t deal enough with poor or working-class whites. In your book, there’s a passage where you’re showing a photograph of some of your relatives to a friend, and your ancestors in the image look quite impoverished. You write that the friend compared the image to Depression-era photographs of people starving in shacks, and you use that as an opportunity to talk about your ancestors’ struggles with class.

MN: Yeah, absolutely. When I was talking earlier about my mom’s mother’s family and the assumptions that I had made that they would never have been involved in slavery and enslaving people, I was sort of inferring that from the fact that my grandmother was very poor, that her parents had been very poor. There’s a photo of an emaciated horse in addition to the one you mentioned of my great-grandfather and my grandmother and her little sister in 1914 or thereabouts. So there’s no denying that these were incredibly poor people who had a really difficult time of it. But their ancestors and my ancestors through them still participated in these really terrible wrongs. I think it can be hard for us as human beings sometimes to hold the idea that someone could have been persecuted themselves or have had a very, very difficult time. That wasn’t fair. You know, for class reasons or other reasons. And at the same time, these people may have oppressed people, persecuted people or may have come from very recent ancestors who did. And so one thing that’s been important for me is continuing to feel compassion for my grandmother and my people through her who experienced hunger and hardship.

JD: The subtitle of your book is “a reckoning and a reconciliation.” We’ve talked about the reckoning and I want to talk about the reconciliation piece. Part of my story is that my paternal grandfather was in the Klan in the 1920s, and he was also the grandfather that molested me when I was a child. And so, to be perfectly honest, I struggle with the reconciliation part.

MN: The reconciliation piece is tricky. How you feel is how you feel. But you know, and it’s also important to say that I think the reconciliation within the family is different from the reconciliation more broadly, that needs to happen outside the family. So I would never ask other people to forgive my family for what they did. And I feel a responsibility for continuing to reckon with that and to listen for my responsibility to advocate for reparations and to be open for whatever responsibilities I may have as a result of the broader harms that my family did.

I don’t anticipate, for example, having a reconciliation with my father in this lifetime. There are certain people who are not safe to have around us and that’s just a reality. It’s taken me many, many years of therapy, many, many years of introspection, and many, many years of meditation, that all together have largely helped me get to a place where I cannot endorse my ancestors’ behavior but acknowledge it and feel reconciled to the reality of it. Then, I can use all of this contemplation and meditation and what have you as a way or seeing how I can show up better in the world, you know, so that I don’t feel kind of filled with rage toward them or feel avoidant around it and stuck on that. Now I feel this clarity about what they did and what they have passed down to me that I might want to take forward and what they have asked down to me that definitely should not be part of what I carry forward in my life.

JD: That’s great and very helpful. Thank you. That takes me to my last question, which is that near the end of the book, you write, “I didn’t plan to have biological children or to adopt,” and I found this fascinating as someone who has also very happily chosen not to have children. As it relates to the themes in your book, I wonder how you think about your place as an ancestor rather than only as a descendant?

MN: That’s an interesting question. I do believe in spiritual ancestors and chosen ancestors. In this book. I wanted to limit it to the questions around biological family and family of origin. But yeah, I mean, we admire people who have helped us in some way as ancestors can also be so spiritually enlarging. You know, I do have a stepdaughter. I do have godchildren, even though I’m not Christian and I do have nieces and nephews and I hope that I might serve some kind of “auntie-adjacent-ancestor” role for them. I do I think there’s a way in which some of us can be called to these kinds of contemplations and reckonings, that we have more time outside of that framework of family to really delve into it and ponder it, whereas if we were changing diapers and taking kids to practice and all of that, we might not have been able to go as deep with it.

JD: That’s a really interesting insight. So we have all sorts of relationships and connections that are family but not necessarily biological. It’s an interesting place to think about how we do cultural repair that’s ancestral and that’s also taking into account these other sorts of kin relationships.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.