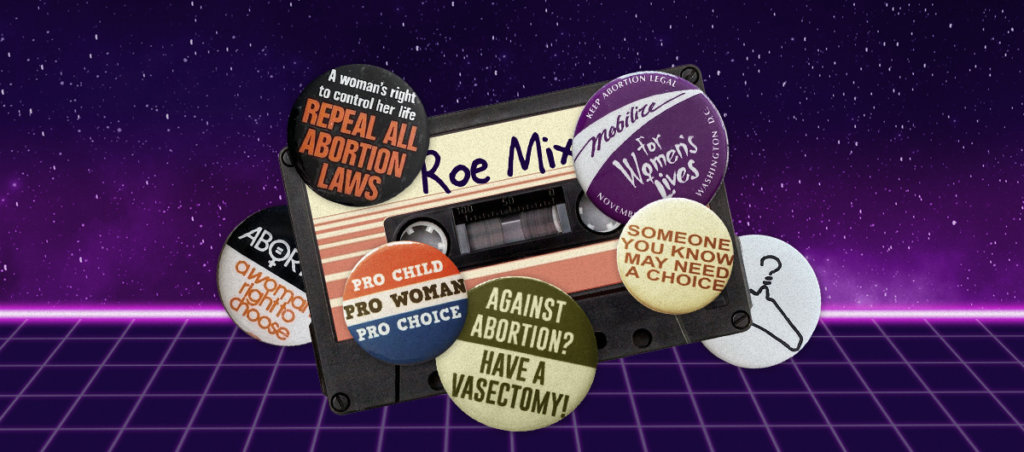

Gen X has had the right to safe, legal abortion for most of their reproductive years. To see it die in their lifetime is a harrowing reflection of how America has changed.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In 1973, when the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade that women had the right to non-criminalized abortions, the first Gen-Xers hadn’t yet started having their periods: the youngest among us would have been 8 years old. So while Roe gave Baby Boomer women—who were 27 and under at that point—the ability to live out many their reproductive years with some sense that their life choices need not be so intimately tied to their bodies’ reproductive imperatives, what it really did was give Gen-Xers (and those younger than us) the secure knowledge that any so-called fuck-ups need not define our subsequent 18-plus years if we didn’t want them to.

And now, as the sun is setting on our generation’s natural reproductive years, so too is it setting on Roe v. Wade as we’ve known it.

On Monday night, Politico published a draft that had been leaked to them, revealing the majority decision by the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade. The draft, its authenticity confirmed this morning by Chief Justice John Roberts, suggests the Court has already voted and the ruling is essentially a done deal; what remains to be done is just drafting the legal reasoning behind ending a right three generations of women have fully known their whole lives to be theirs.

The decision will essentially revert the power over women’s reproductive autonomy to the states, where anti-abortion groups have waged the fiercest battles to restrict access to abortion, instituting mandatory ultrasounds and waiting periods, restrictive laws on providers, bans based on dubious understandings of fetal development and, occasionally, outright bans, often in the hope of convincing the Supreme Court to undermine if not overturn Roe.

And, in the wake of a decision like the draft Politico published, nine states still have pre-Roe bans on the books that will immediately go into effect, and another nine have so-called trigger bans that will take effect (or take minimal effort to put into effect) once a decision overturning Roe is published. Four states will immediately ban all abortions after six weeks, and an additional four are expected to ban abortion within a year.

There are approximately 73 million women of reproductive age (15-49) in the United States; the Guttmacher Institute estimates that about 40 million of them live in these states.

Bush-appointee Justice Samuel Alito, a devout Catholic whose beliefs about abortion have always been plain, is the author of the draft opinion; in it, he compares the wrongness of the Roe v. Wade decision to Plessy v. Ferguson, which allowed Jim Crow to flourish in the American South, and Korematsu v. United States, which allowed for the detention of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

He also refers to abortion providers as “abortionists” and suggests that the decision is on the side of racial righteousness because Black women have disproportionately more abortions, without bothering to figure out why those people who are disproportionately economically marginalized might seek abortion care more often than those who are not (like access to contraception and other health care).

It’s rare that a news article prompts a response from major government leaders—but President Biden, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer had already weighed in by Tuesday morning.

It’s also rare that the Supreme Court issues a decision that will broadly lead to an outcome with which 80 percent of Americans disagree: Only 19 percent of Americans in 2021 thought abortion should be illegal in all circumstances, according to Gallup. And yet, for more than half of women of childbearing age, abortion will likely be illegal in all circumstances before the next presidential election.

And, of course, because the right to an abortion was grounded in the same legal reasoning as the right to access birth control—and because many people in the anti-abortion movement define emergency contraception, IUDs and even hormonal birth control as “abortifacients,” despite the science to the contrary—there are a whole host of other state-by-state restrictions coming that will exacerbate the volume of unintended pregnancies that would typically prompt someone to seek abortions.

This is not the version of reproductive choice that most Gen-Xers had for our reproductive years.

With abortion rights goes our sense of security

It is hard to remember when I knew I had the option to stop being pregnant, if I got pregnant; I’ve been trying for months.

I’m sure it came up during one of our two “sex ed” days during junior-high-school health class but, having happened in 1990, they are more memorable for the frank discussions we had about HIV/AIDS and how to prevent it and other sexually transmitted infections. (Bless the poor woman who had to answer my classmate’s troll-y question about whether you could catch anything from fucking a dead or live animal; I think the other kids paid him $1.) And it definitely came up in the sex-ed section of 10th-grade health class, which I took the summer before, with the older kids who’d failed it once and needed the credit to graduate.

But I don’t remember absorbing the existence of legal abortion as a surprise or as new information. I suspect, actually, that it was inadvertently part of my birds-and-the-bees education, which is still a sore point between my parents 40 years later. Though I don’t remember it—I was only 3 or 4—family lore holds that I was on a walk with my dad when I asked where babies come from and, not wanting to pass off the hard stuff, he told me.

The answer from my dad (whose mother had him—a whoopsie-baby—when she was 48), wasn’t particularly satisfying to his pre-school daughter, so I kept asking more and more specific questions. My parents still won’t discuss what exactly I got told that day, but I came away with a specific sense that my body could eventually grow a baby… but that I didn’t have to; I was big on what I didn’t have to do from a very young age, so it feels right that I would’ve asked that question. (My understanding of what I was told was also incomplete; I remember knowing that two men couldn’t have a baby together, but I was pretty sure two women needed nothing from a man to do so.)

So by the time my Catholic Sunday-school teachers told us it was wrong, I didn’t believe them. That sense that not everything in the Bible is morally accurate was likely assisted by my fourth-grade unsanctioned reading of the entirely of Deuteronomy in CCD class, including about how all rape victims had to either marry their rapists or be stoned to death alongside them, and the fact that men who lost one testicle weren’t allowed to go to church anymore; I told the testicle thing to everyone else in class.

I remember quite clearly the girls in high school who were rumored to have had abortions, and even more clearly the girls who didn’t and dropped out to be “homeschooled” or had to give up certain activities as their bodies swelled as the school years went on. I remember having my own pregnancy scare—I was two whole days late—and crying hysterically in the shower trying to figure out how to get together the rumored $250 that an abortion cost at the Schenectady Planned Parenthood when I only made $4.35 an hour and the bus to get there and back would be $2, too.

But I remember being sure I’d have one; I wanted to get out of that village I grew up in, I wanted to go to college, I wanted to use my brain and not be limited by someone else’s use of my uterus. I wanted more for myself, and I knew a barely-post-SAT pregnancy would limit how much more I could ever have.

My period came two days later. My pediatrician put me on birth control the summer before I went to college, telling me too many of her patients came home pregnant when they didn’t want to be and had to make much more difficult choices than whether or not to take a pill.

In the end, or almost the end, I have never needed to exercise my right to an abortion. I’ve had the access to health care and enough financial means to be on some sort of birth control since Dr. Kim gave me that prescription, even though I had to pay $250 out of pocket for my first IUD in 2002. And, unlike with others, each method was seemingly effective.

But I always knew it was there; I always knew I could if I needed or wanted to, and the ability to make the choice for myself—until it wasn’t an option for me anymore—made me feel like I had many other choices.

And though access to abortion in other states has been closing, little by little, since I had that first pregnancy scare, it was never something that others had zero possibility of accessing … until now, when the generations just behind me are seeing their choices cut off at the knees while they still might want or need them. And I don’t know what other choices they’ll feel like they can’t conceive of, or make, when this one no longer exists for them.