As we await the final nail in the 'Roe' coffin, Linda Villarosa, author of the groundbreaking 'Under the Skin,' talks with DAME about the horrifying history of sterilizing Black Americans—and the alarming rates of infant and maternal mortality that continue to this day.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Any day now, the Supreme Court will likely strike down Roe v. Wade, ending nationwide legal abortion after nearly half a century. That landmark decision, issued in January of 1973, was supposed to give American women the definitive right to bodily autonomy. But Roe’s promise has remained elusive to many Americans, particularly Black and brown women, in horrifying and tragic ways.

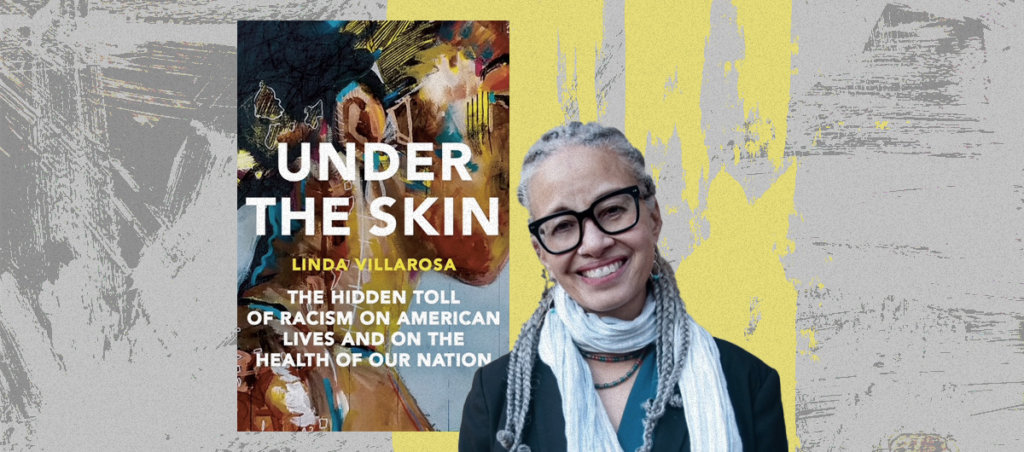

In her new book Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation, veteran reporter Linda Villarosa elucidates on the myriad crises that Black Americans face, including reproductive injustice and a maternal and infant mortality crisis. She reframes the roots of poor health outcomes for Black Americans as an egregious result of centuries of oppression, discrimination, and bias. From the unequal treatment Black patients receive from health care providers to the invisibility of Black emotional pain to the effects of environmental racism, Villarosa systematically dismantles pervasive myths that Black people are responsible for their own poor health outcomes, whether through genetics or behavior, through painstaking reporting that clearly lays the blame where it belongs—racism. The result is a powerful indictment of the pervasiveness of racism in American health care, and a clarion call to disentangle this scourge from our society and fulfill Black Americans’ right to life and liberty.

“Yes, something about being Black is creating a health crisis, and that something is racism,” she writes in Under the Skin. “It is the American problem in need of an American solution.”

Villarosa spoke to DAME about her groundbreaking work amid this tenuous moment in America.

You wrote this book after a widely read New York Times Magazine piece in 2018 on the alarming rates of infant and maternal mortality for Black Americans. You cover so much ground in this book, from mental health to the effects of pollution on Black Americans. And then, COVID and the Black Lives Matter uprising of 2020 happened. What was the process like of fleshing this story out amid those seismic moments?

LV: Every story I do, I overreport. I’ll interview like 30 people for an article, and I don’t even use many at all. I’m always writing all of these tangents in every story, including the maternal mortality and infant maternal mortality story, and my editor would always cut it out of the story. I had this huge compilation of sources and the stuff that Black people have been dealing with and thinking, but didn’t always have evidence at hand. So I thought, let me just put it all together in a book so that is really why I decided to write Under the Skin.

I hate that both the murder of George Floyd and the pandemic were confirming [my reporting] for me in real time, and unearthed even more of these racial disparities and medical inequalities. It was useful. Here it is, we’re living in this moment right now, this is what I’ve been writing about, talking about, publishing about.

You detail the tragic story of 14-year old Minnie Lee Relf and her 12-year-old sister Mary Alice, who were taken from their homes and forcibly sterilized in Montgomery, AL in the summer of 1973, and their ultimate lawsuit that exposed widespread forced sterilization across the country. That happened several months after after Roe v. Wade was decided in January 1973. What do you think the juxtaposition of those two cases says about reproductive policing of Black women and girls?

LV: One of my reviews, at the New York Times, really said it best. The author was saying as she was reading about the Relf sisters in my book, it was also the time when the Roe decision got leaked. She was doing it at the same time. She was reading all these posts on social media that OMG we’re going into another Handmaid’s Tale scenario. Her comment was: Black women have always been in this Handmaid’s Tale scenario; it’s only new if you’re a white woman. Look at what happened to the Relfs. Thirty-two states had eugenics laws on the books that said it was okay to sterilize women who, in most cases, were sort of degenerate women and men who were “degenerate” or who were “feeble-minded.” It speaks to the way we deal with reproductive justice and reproductive health in America. It is unfair. It is unequal. And it hasn’t gone away. People are still being sterilized. Recently, we found out that women were being sterilized in ICE facilities. Certainly, Roe v. Wade is so difficult right now and it’s hard to believe. I write about this stuff. I am in it all the time, but I’m like, what is happening in our country?

You write that Black Americans may be the canaries in the coal mine for health disparities caused by oppression for other people. How do you see the effects of discrimination, both for Black folks and other marginalized groups targeted by restrictive legislation, like trans people, queer people, and folks with uteruses?

LV: It really came from Arline Geronimus’s idea of “weathering.” When your body is harmed by discrimination by biased by aggressions, microaggressions, by cruelty, there’s a kind of premature aging that happens. I like her poetic term, “weathering,” because it speaks to how a house is weathered by the storm—you know, the paint is chipped off, the shingles fall off the roof, the shutters fall off—but also how a house weathers the storm. It’s the idea that if you have community, family, and kinship, you can weather the storm of living in America. She studied Black people and the the effects of what happens when you are faced with discrimination, day in and day out. It’s like the “fight or flight” syndrome over and over again, so that your blood pressure goes up, your heart rate goes up, your cortisol levels go up. If you experience this everyday racism, it takes a toll on your body.

But it’s not just Black people. There’s nothing sacred about our experience, except that we’ve been going through it for so long––generations, really. It started 400 years ago. It didn’t end when enslavement ended. We have this really long track record of this happening to our bodies. That’s why I said we’re the canaries in the coal mine. We’re the ones whose bodies were commodified and studied. We’re the ones where there’s been all this research on racial health disparities, on discrimination, on ill treatment in the health care system. But it’s not unique to us; it’s just more intense and more long term.

You hearteningly state at the end that you still have hope. How do you feel in this moment, with all that we’re facing as a country, particularly Black folks?

I’m really hopeful. I have seen changes happen in the past couple of years. I mentioned in the book that I had been at a conference at the beginning of 2020, and we were saying, “Let’s not say the word racism or even in public health.” I said that! I was the one who was resistant. Now it’s like, wow, we’re saying the words––racism is a public health threat. We were kind of stepping around it, being really cautious with that wording, but that’s really what it is. I think that in the past, there was this idea that if you look at racial health disparities and medical inequality, there was something about being Black that was causing this. Black people live shorter lives and have higher rates of infant maternal mortality because we’re doing something wrong or something is wrong genetically with our bodies.

Now, that idea is really fading away. It’s not race that’s responsible, but racism. The treatment that you get, the lived experience of being a Black person or other person of color in America, really affects the body and affects our access to health care and the quality of health care we received itself.

I also detail [in Under the Skin] how medical students and the health care providers of tomorrow are really energized [around racial justice]. They were in high school or college when the Black Lives Matter movement started. Not just Black people, people of all races, are really energized by that. Now, they may be in nursing or medical school. Trying to change the way medical practice is done and medical education is structured. I’m really excited for [this next generation] to be a different kind of health care provider.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.