The National Right to LIfe Committee’s model law puts journalists and outlets who cover abortion squarely into legal crosshairs. And it’s just the latest in a long history of tactics used to silence coverage of injustice and marginalized people.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

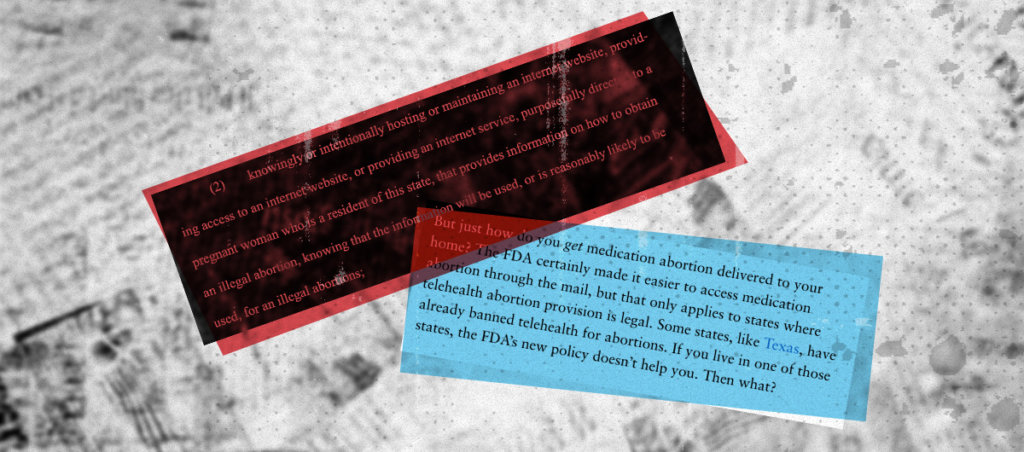

What does it mean for a website to “encourage” abortion? New anti-abortion model legislation released last week by the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) would force anyone who publishes work online to grapple with that question, putting journalists who cover abortion squarely into legal crosshairs. The model legislation—which NRLC hopes will be adopted by state legislatures around the country—would subject people to criminal and civil penalties for “aiding or abetting” an abortion, including “hosting or maintaining a website, or providing internet service, that encourages or facilitates efforts to obtain an illegal abortion.” Unsurprisingly, the text offers no guidance on how broadly or narrowly the provision might be interpreted: Does it cover an article on how medication abortion is accessible by mail, or reporting on the medical consensus that it’s safe? What about a story on the opening of a new abortion clinic, or one covering the work of abortion care clinicians, advocates, and doulas? Is it too “encouraging” for a website to simply remind readers that despite the leaked draft Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Whole Women’s Health, abortion remains legal, and people are free to keep their appointments? If so, along with abortion providers and advocates who already face constant surveillance, harassment, and violence from the U.S. anti-abortion movement, journalists at trusted news organizations like Prism, DAME Magazine, Rewire News Group, Scalawag, and others could face legal jeopardy simply for doing our jobs: fighting misinformation, and providing readers with up-to-date, deeply reported, and fact-based information that reflects the state of the nation and helps them navigate their place within it.

Of course, that’s the problem. It’s no coincidence that the legislation would attack the entire informational infrastructure around abortion, up to and including news coverage. News is information, and information is power. When people are empowered with knowledge about their rights and how to exercise them, it’s much more difficult for the state to coerce and rob people of their bodily autonomy. Leveraging the power of information and journalism on behalf of marginalized people—which includes people seeking abortion care—is inherently threatening to power, which is why power so often resorts to suppressing speech to keep us in our places.

In the United States, there’s a long history of efforts to silence information concerned with the rights of marginalized people, and that’s always included the work of journalists. In the 19th century, for example, Congress passed a “gag rule” to prevent abolitionists from petitioning against slavery, and southern states passed laws that outlawed anti-slavery speech entirely. Critically, both historically and today, speech suppression laws not only hand bad-faith actors the tools of criminalization and fines to silence those they disagree with, but they can also normalize physical violence. Indeed, violence against journalists was widespread in the 19th century, and—crucially—not confined to the places where such anti-slavery speech was criminalized: In 1837, a pro-slavery mob killed abolitionist newspaperman Elijah Lovejoy and destroyed his printing press in the “free” state of Ohio, while the following year in Philadelphia, a similarly-minded mob burnt down the abolitionist meeting space Pennsylvania Hall, which also housed the offices of abolitionist newspaper The Pennsylvania Freeman. Even after slavery was abolished, journalists faced constant threats to their safety for daring to accurately report on injustices like lynching, foremost among them being Ida B. Wells. And even in the present day, it’s clear that speech-suppressive laws are part of a larger constellation of practices that embolden violence against the groups they target. Witness the spate of anti-gay and anti-trans violence in the wake of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law, and the primarily Black and brown teachers who’ve faced harassment, violence, and even death threats following “anti-CRT” suppression of discussions about racial injustice in American society. Now, with a law specifically targeting abortion-related speech, the risks are especially dire since so many of the journalists leading the way on reproductive rights and justice reporting are women of color, who already face disproportionate harassment.

While no state has yet taken up the NRLC’s model legislation, there’s plenty of reason to be concerned, since both speech-suppressive and anti-abortion legislation like this “go viral” with alarming frequency in recent years, as with the many copycats of Texas’ highly restrictive SB8 abortion ban and Florida’s homophobic “Don’t Say Gay” law. In fact, the NPLC has already seen at least one of its model anti-abortion laws adopted in Nebraska. Should this model legislation gain traction after the anticipated fall of Roe v. Wade, it would lead directly to the criminalization of journalists and news outlets, especially those led by BIPOC, women, and other marginalized people who’ve been at the center of the abortion debate.

And the First Amendment may not offer much refuge. The legislation prohibits “encourag[ing] abortion access,” which might mean virtually anything—and that’s by design. With laws like these, both the cruelty and the vagueness are the point. Conservatives have used precisely the same playbook with “Don’t Say Gay” laws and so-called “anti-CRT” legislation—the ill-defined and vaguely-worded laws leave so much uncertainty about what’s prohibited that people start policing their own speech out of sheer caution. The result is that a vast amount of speech is chilled without the state ever having to lift a finger for enforcement. While one might expect such clauses to be struck down as First Amendment violations, given the vagueness and overbreadth, it’s no longer a given that the U.S. Supreme Court or the lower federal courts would adhere to longstanding precedent to do so. Overwhelmingly Republican-controlled state supreme courts probably would not stand in the way either. Thus, if the model legislation is adopted and allowed to stand, deep-pocketed anti-abortion activists could use it to tie up news outlets in costly litigation, wasting both time and money crucial to our continued operation.

As laws like the NRLC’s model threaten to proliferate, it’s more urgent than ever to support journalism that doesn’t treat abortion like an abstract “culture war” issue, but that engages seriously with the human impact of restricted access. That means continuing to read, share, offer financial support to your favorite outlets when possible, and also supporting organizations that provide legal assistance to newsrooms. In the meantime, for those of us working in media, even if we can’t look to the legal system for protection, we must continue reporting the facts on abortion, holding the powerful accountable, and shining a light not only on anti-abortion zealots, but on the critical movement work being done to defend abortion access around the country. As much as legislation like the NRLC’s strives to create a media that’s cowed into silence or only produces toothless “both sides” reporting on reproductive rights and justice, it’s on all of us to sound the alarm, resist, and keep “encouraging” readers to stay informed and take action.

[This article was originally published by Prism]