Is anti-MLM content just taking advantage of people sucked into MLMs for entertainment?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

With her blue kitchen in the background, YouTuber Madison Harnish, who runs the channel Cruel World Happy Mind, talks about how multi-level-marketing companies (MLMs) target stay-at-home mothers by promising an ideal lifestyle. Members of MLMs, Harnish says, create YouTube videos about how they are able to balance being an involved mother with making money to support their families to help lure in new members. “This person is targeting people that are dealing with very specific issues that have to do with child care,” Harnish says in the video, which has been viewed more than 175,000 times.

MLMs are direct sales companies where consumers sell products, which could also be considered pyramid schemes. Pyramid schemes are illegal in the United States, but companies get away, or try to get away with it, but claiming people are just selling products. Pyramid schemes got their name because people at the top, who make the most money, recruit people below them, and the people below them recruit others. People at the top make money too when people they’ve recruited get other people to join the scheme. In MLMs, people near the top are the ones making the money, and around 99 percent of people in MLMs lose money according to a 2011 report from the Consumer Awareness Institute. This is what makes MLM tactics, like telling people they can be their own boss and make money while taking care of their kids, so predatory.

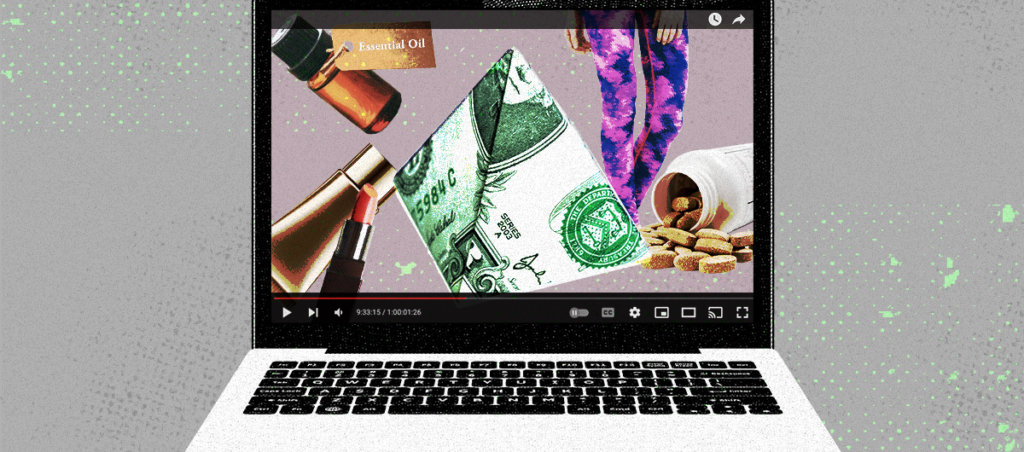

Social media, including YouTube, has been a tool to help people, mainly women, promote their MLM products and show off their aspirational life. Thus, it’s not surprising that creators have used the same platforms to critique MLMers and the false lifestyle they are promoting. Over the past several years, more and more YouTubers have been making anti-multi-level-marketing videos discussing the tactics of these unethical businesses, with some videos getting hundreds of thousands, if not millions of views. Even if their intentions are not nefarious, anti-MLM YouTubers gain a following because they are piquing people’s interests in MLMs and other scams. They claim a world without MLMs is aspirational, just as MLMers claim their lifestyle is desirable, too. Anti-MLM content on YouTube operates on a thin line of validating and helping people who have had negative interactions with the industry and being just another form of scam entertainment, as many of these videos outline how companies are set up to exploit people.

The people who watch anti-MLM content on YouTube, TikTok, and other platforms typically have some connection to MLMs, whether they almost joined one or know people who have. Some want to research possible business ventures and are looking up companies, some may be considering leaving MLMs, and some may just find how MLMs function to be interesting. And as with members of MLMs, many of those creating anti-MLM content are women, who are also more likely to be recruited to join MLMs. According to a 2017 report from the AARP Foundation, 60 percent of people in MLMs are women.

But the anti-MLM community is not without its critics. Some anti-MLM creators make YouTube videos and TikToks that make fun of people at or near the bottom of the MLM pyramids. That’s just exploiting people who are already being exploited by an MLM company for entertainment, who are not taking advantage of people unlike those higher up the pyramid.

Anna Iovine, a reporter at Mashable and viewer of anti-MLM YouTube videos, noted that both pro-MLM YouTubers and anti-MLM YouTubers need each other to create content. Most anti-MLMers say they want MLMs to end, but this effort is not solely altruistic, as bigger channels also make money off of these videos. “I wonder, as more people watch this anti-content, more people realize that it is a pyramid scheme, and perhaps [MLMs] will get banned, I wonder what will happen to the genre,” Iovine said of MLM YouTube content. “These people need each other. It’s sort of like a Batman and Joker situation.”

MLMs don’t just take advantage of people financially and socially; some MLMs also promote pseudoscience, which is incredibly dangerous. Ontario-based English teacher Sara Blair first became interested in MLMs because of the language-based tactics they use to recruit members. After she was diagnosed with cancer, Blair did not believe the MLM-promoted lie that essential oils were an adequate treatment for her health condition,which encourages those with cancer to delay chemotherapy and radiation. There are no scientific studies that show that essential oils can prevent or cure cancer.

“I had one person tell me essential oils would help me, but they did not have any [medical] credentials, and I already did not believe that,” Blair said. While it’s dangerous, Blair said MLMs have “become a big joke in the cancer community,” and they share memes to cope with the dark situation of people trying to take advantage of cancer patients.

Now, Blair shares anti-MLM YouTube videos and other content on her social media, hoping that it will reach people she is connected with who are in MLMs, as she recognizes how dangerous they can be. “I’ve lost friends, because I’ve posted [about] it,” Blair said. “I really do believe it’s got a cult mentality.”

Anti-MLM content is fairly new in comparison to MLMs. For the past few decades, members would mostly sell their products to their neighbors and family members within their immediate communities. But social media has expanded MLM’s scope as a recruiting tool—and for people to speak out against MLMs.

Antonella Fleitas, who lives in Argentina, was looking for virtual-assistant opportunities when she found herself working for an MLM. “I thought it was a services company, and then I was suddenly in a WhatsApp group with all the motivational messages,” Fleitas said, who decided to walk away after being greeted by MLM “hunbots.”

The “hunbots”—the people who reach out to prospective MLM members with a “Hey hun, I have a new opportunity for you”—have almost become a caricature in the anti-MLM content space. Analyzing the actions of these hunbots, as many anti-MLM creators have noted, is complicated. Some hunbots may know that getting people beneath them is how they’ll make money, while others may think they are actually giving someone else an opportunity.

Anti-MLM content has taught people like Fleitas to cut loose from these scams before they get sucked in. “Everything is organized to seem [like] something that it is not, [and there are] all the training and how they teach people how to lie,” Fleitas said.

Anti-MLM content is often created by former MLM people, so they have experience with their predatory nature first hand, like YouTuber Josie, who runs the YouTuber channel Not The Good Girl, and Kendall Rae, a true-crime YouTuber, who talks about the way she was sucked into Mary Kay Cosmetics and lost money whenever she covers a case involving an MLM.

But other ex-MLM people may be hesitant to share their experiences, for fear of being judged for being drawn into MLMs in the first place.

“They are often embarrassed at how they behaved when they were in the MLM, the money they lost, and the fact they were taken in,” said psychotherapist Hannah Martin, who hosts the podcast “Get Rich Slow.”

Anti-MLM content stands in opposition to the PR of some MLMs that have been running for decades. An issue is that some companies that have turned into MLMs seem reputable. Avon, for example, was founded in the 19th century, and it used to be a direct sales company. Because people trusted their makeup, when they have become more MLM-style business in the past 20 years, it has been more challenging to bring down certain tactics from this company.

Throughout the mid to late 20th century, stay-at-home mothers and other people would hold parties to sell products from direct-to-sell companies, like Tupperware parties. It was a way for women to create communities, and now, MLMs are tearing up friendship groups due to their cult-ish practices. Melinda Wedde, a Pittsburgh-based mom and yoga teacher originally from Indiana, grew up going to “parties” in which moms would get recruited to become salespeople and to buy products. In fact, Wedde’s first make-up kit was from Mary Kay Cosmetics, and her grandma was an Avon lady. Over the past few decades, many of these direct-to-sell companies have become more explicitly MLMs.

“A lot of it is regional, and that’s part of the predatory practice,” Wedde said. As an article from Vox notes, MLMs have traditionally been more popular in the Midwest and South, but they have spread throughout the United States. Wedde shares anti-MLM content because she doesn’t “want people to lose money” or “fall in too deep.”

If MLMs were banned internationally tomorrow, people will continue to watch videos on companies like Avon and LuLaRoe, tracing their rise and their fall. But, as some anti-MLM content points out, we’re going to need better policies in the United States to support those MLMs prey upon. So, they are not put in a place where they feel like they have to pursue risky career options that can hurt them financially for a potential positive trade-off.