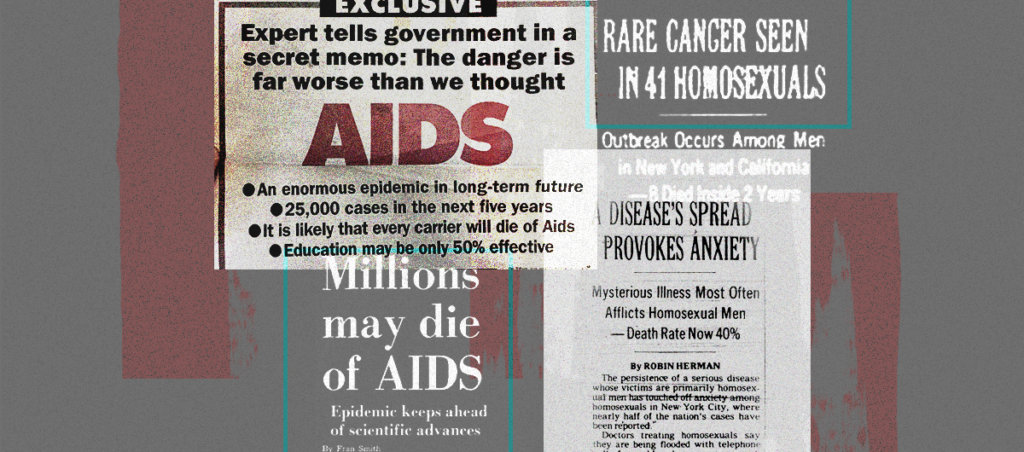

Legacy media has reintroduced shame-based conversations from the AIDS era centering on behavioral change to contain an epidemic without mentioning vaccines. Have we learned nothing?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

A simple joy: I met one of my dear friends at a bar. It had been awhile since I’d seen him, so I pulled him in tight, and kissed him on the cheek. Like so much queer touch, the feeling we shared was more profound to me than what appeared on the surface. I’ve spent so much of my life policing the ways I was allowed to touch men, or long for their touch, and reveling in it now feels spiritual.

My friend hadn’t been in a crowded space for nearly six weeks. We were at The Eagle, NYC, a legendary gay leather bar. Since HIV PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis medication) and U=U (undetectable=untransmittable, i.e., the viral load of an HIV-positive person controlling their infection with drugs can’t transmit the virus to another person) turned casual and raw sex into safe sex for HIV transmission, The Eagle has become a place whose corners are usually filled with pleasure.

When I invited my friend for a drink, he asked, “Aren’t you afraid?” I was not. Then he said, “Anywhere but a gay bar! I don’t want to be seen. I have a scar, still, on my neck.” But the only time we could meet was on a Saturday night that I’d had planned to meet with another friend at The Eagle.

“It feels so good to hug you,” I told him, first because I knew he needed to hear it. Only after I said it did I realize how true it was. Showing him my touch not only without fear but with enthusiasm and care healed something not in him but in me.

My friend just recovered from monkeypox virus (MPV). He’d been struggling with stigma, feeling like he did this to himself. Just after his diagnosis, I texted him, “You didn’t do anything wrong babe. We failed you.”

The Washington Post and The Atlantic recently published articles that argued it was on “Gay Men,” as the first headline reads, to fight monkeypox “ourselves.”

This friend wasn’t able to secure a vaccine appointment until mid-July because getting an appointment was next to impossible. When he finally got vaccinated, he found the first pox lesion on his arm later that same day. For the next five weeks, he sat home watching his skin explode in waves, trying to focus on work, bad TV—anything to take his mind off it, if only for a moment.

MPV is an orthopoxvirus related to smallpox, endemic to Central and West Africa. Smallpox vaccines, like Jynneos, also prevent MPV infection, but they were not used in the endemic region.

In May 2022, MPV started to spread globally in queer sexual networks. That month, queer activists in the U.S. insisted that the government take this seriously. Tests were not widely available until mid-July and vaccines remain scarce. After one particularly disastrous meeting trying to get federal assistance, an activist—an ACT-UP alum from the 1980s and 1990s—reached out to me and said, It’s time to have a hard conversation.

Because the government had failed, it was time to tell publicly queer folks to cool it with the sex, if only for a time. We’d already been having these conversations privately within our social and sexual networks for weeks. Together with a group of colleagues, I co-wrote guidance that we felt came up from the community most at risk. A lot of people are sick. Monkeypox sucks. We can do risk reduction—including reducing the number of sexual partners we have—until the vaccine is available. Following the publication of our guidance, the CDC and New York City followed suit.

Yet, weeks after the clear guidance from queer folks and public health leaders, writers continue to push this narrative that no one is being honest with “gay men” about the sexual risk of MPV spread, and everyone is afraid to tell “gay men” one thing: to not have sex.

Individualization of the responsibility for public health on any person or community is dubious. “Gay men” are pretty awesome, but no one has yet given us the ability to procure vaccine from Bavarian Nordic (the makers of Jynneos). Additionally, calling for us “ourselves” to stop MPV will ultimately place the blame on us when, without vaccines, we failed.

Implying that gay men can fight this epidemic “ourselves” through behavioral changes implicates those who are already ill or recovered as its cause—a double indignity. The infection is quite enough. And this is wrong: If the federal government had acted with urgency on testing and vaccination, most transmission, “we could have stopped this in its tracks, as epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves said on NPR.

Writing for the Washington Post, Benjamin Ryan opens his piece with Larry Kramer’s 1983 invocation that HIV/AIDS had to be taken seriously as a community crisis. Kramer was famously right about this, and went on to co-found the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Ryan correctly points out that Kramer advocated that gay men, facing the AIDS crisis, change their sexual behaviors, and many did. Condoms became such an important symbol of community care that AIDS activists wrapped North Carolina senator Jesse Helms’s home in a giant condom to protest federal inaction on AIDS funding.

Ryan cites a 1983 safer sex pamphlet as evidence that gay people often lead on sexual harm reduction. “Ultimately,” he writes, “the push helped dramatically reduce sexual risk taking. HIV transmissions dropped among gay men accordingly.” This is a sleight of hand: Risk reduction helped “dramatically” and HIV transmissions dropped “accordingly.” The latter numbers aren’t linked or cited in Ryan’s writing.

Let’s look at the data: New HIV cases fell from a peak of over 130,000 infections per year in 1983 in the U.S. to around 58,000 infections per year by 1986 through 2007. During this time, the proportion of infections in Black and Brown people rose. Only in recent years, when PrEP came online as an HIV preventative did cases fall below 50,000 per year. In 2019, the CDC reported just under 35,000 new HIV infections in the U.S.

Is a reduction in new cases from 130,000 to around 50,000 per year dramatic? Certainly, particularly for the lives saved.

To argue that nothing else happened between 1981 and 1985 besides gay men teaching one another how to have safer sex—including the advent of HIV tests and the community catching up to a virus with a years-long incubation period—is specious at best. That HIV causes AIDS was shown conclusively in 1983 and the first HIV tests were developed around 1985.

But Ryan would have you believe that changing how you have sex is a silver bullet. Condoms and behavioral changes implemented in the 1980s were followed by over a million new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. The behavioral changes also came at an emotional cost; in my book, Virology, I detail a friend’s story of men climbing to their rooftops at sunset in Hell’s Kitchen to jerk off together, far apart, they were so afraid of touch. This is a generational trauma I feel myself.

Furthermore, Black and Brown gay men and trans folks got left behind in HIV prevention—and they now bear the highest burden of years of failed risk-reduction policies, due to years of systemic neglect by healthcare systems, as detailed in the new book The Viral Underclass, by Steven Thrasher.

Ryan may ask if Black queer+ men having more risky sex that puts them at risk. Not according to a study from The Lancet: In the U.S., Black queer+ men (the study uses “MSM,” which I’m trying to avoid here) have higher rates of HIV, they are less likely to be on treatment, less likely to have health insurance, are more likely to be unemployed. They are also more likely to initiate behavioral changes to reduce HIV risk, including condom use, not using drugs during sex, and reducing their number of partners. If behavioral interventions were the best bet at lowering HIV risk, Black queer+ men would have lower HIV rates than others.

Will this pattern of risk reduction being inversely correlated to disease burden hold for MPV? I don’t know and no one does. Ryan uses HIV risk reduction as a blueprint for success; it’s essential to consider it fully. This is what happens when communities are left to fight infectious diseases “ourselves”: People get sick and die. Black, Brown, and Indigenous people get sick more, a pattern we’re already seeing with MPV.

HIV activists did not insist we discuss only risk reduction and condoms—they demanded that the government fucking do something. It was this larger work that pushed biomedical tools across the finish line. We are still working on global access to these drugs, and many people inside and outside of the U.S. are left behind, along racial, gendered, geographical, and class lines.

For MPV, Ryan critiques the government not for its inability to provide vaccines needed to protect people—in fact, he does not once mention the words “vaccine” or “Jynneos,” a tool that can prevent MPV infection. Instead his focus is officials “play[ing] down the central role sex between men plays in monkeypox transmission and overemphasiz[ing] the uncommon cases that transmit through other means.” This is his characterization of Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, the Deputy Coordinator of the White House National Monkeypox Response—a gay infectious disease doctor with a not-insignificant amount of community trust—who was quoted talking about sex, using words like “fetish gear” and “sex toys” on HBO’s Last Week Tonight.

Ryan’s main point is this: “Until a time when monkeypox hopefully abates, this can and should mean reducing our number of partners, skipping sex parties, practicing monogamy and even being abstinent” (emphasis mine).

But infectious diseases do not magically “abate”; we contain or eradicate or prevent them, not with gays being abstinent or monogamous, as the history of HIV shows us, but by the active use of countermeasures like vaccines and treatments.

This all may well seem like a semantic argument or overly careful word policing, but the way we speak about disease has a direct impact on those already sick, like so many of my friends, and those most at risk, myself included. Susan Sontag wrote Illness as Metaphor in the 1970s, so these conversations about choosing our languages of illness without doing harm to the ill are not exactly new, and something everyone who writes about health should be well aware of. The rise of anti-queer and anti-trans legislation makes it all the more essential to choose one’s words with an eye toward care and away from stigma, no matter how many clicks or followers the latter generates.

But what if monogamy and abstinence are necessary for a time? Well, meeting people where they’re at acknowledges that not everyone has a partner and that sex is awesome and people like doing it. Sex guidance I co-wrote suggested pods similar to COVID social pods: Speak mutually with one or more partners, all together, discuss past risk and vaccination status, monitor for symptoms, and keep sex within the pod. Is this monogamy? Of course not! Will it work just as well? Given the number of people I know who’ve gotten gonorrhea from their “monogamous” partner, perhaps open communication about risk and behavior is better than a blanket assumption of monogamy. Indeed, one key takeaway from a 2015 literature review in the journal Preventative Medicine is that “Relationship status cannot determine which patients are at risk for STIs” precisely because people understand monogamy differently (and many say they are but aren’t). So, simply asking people to practice “monogamy” as disease prevention may also be unscientific.

Writers, including a recent Buzzfeed headline, have said gay sex is “driving” the MPV epidemic, directly placing blame on those who have fallen ill. Buzzfeed changed the headline after several of us highlighted its stigma to the writer. But a few days later, Ryan published another article, for NBC, titled “Sex between men, not skin contact, is fueling monkeypox, new research suggests” (emphasis mine). Yes, it is essential to talk about this virus spreading through sex and to mucus membranes. The use of the words “gay sex,” a stigmatized act in the U.S. (it was illegal in some places less than 20 years ago), as “fueling” an epidemic is troubling. Predictably, within the week, after right-wing “journlist” Andy Ngô posted about a MPV case in a child, several people responded on Twitter with Ryan’s article to imply that the child was a victim of pedophilia. Another post on the same thread was simply a GIF of a double rifle being loaded with two bullets.

The words we use matter. MPV is currently spreading through gay sexual networks; the epidemic is fueled by a global lack of vaccines. Words implicitly place blame, either on a sick person or a failed government.

Finally, Ryan’s mention of “abstinence” shocks. Sex itself is not risky if both partners are open and communicative. These projections from queer sex to inherent risk may be a long-lasting trauma of the ongoing HIV epidemic. It’s important to state that there’s nothing inherently risky about queer sex, not for HIV, not for MPV.

Days later, The Atlantic published another article with the same overall thesis, by Jim Downs. On Twitter, Dr. Downs claimed his article was not sex negative because he opens with a scene in a bathhouse in 1927. The scene? Empty “ghosts” of men wandering without making eye contact. In The Atlantic, Downs admits, “This description was hardly a ringing endorsement.” He even evokes a “solicitous suburban Dracula.” This description of a bathhouse sounds pretty “sexphobic”: no pleasure, only shamefully averted eyes and creatures from literal horror stories.

Dr. Downs isn’t done with bathhouses. He cites Larry Kramer’s Faggots, a pre-AIDS crisis novel published in 1978 with judgmental portraits of gay sex lives in New York City: “Kramer’s book indicted orgies,” Downs writes, “urban bathhouses, and sex-filled summers on Fire Island, which, he believed, prevented gay men from having intimate, monogamous relationships. Others shared many of Kramer’s concerns.” What about those of us who don’t, though?

This use of Larry Kramer in both essays requires a discussion of his outsized, important, and controversial role in the HIV/AIDS response. Kramer was effective and cantankerous, and this never changed. He initially called the use of PrEP instead of a condom “cowardly” and wrote an essay in Esquire saying that “activists got us these [HIV] drugs, but once we got them, we stopped fighting and returned to partying.” For anyone who might argue that the late Kramer was in his 80s by then, and therefore no longer interested in sex, I would like you to meet the 80-year-old writer Samuel Delany, who wrote in The Boston Review about his pizza-filled sex parties for queer elders. Both Downs and Ryan cite Kramer as a voice of reason, but it may be puritanism that connects these three writers.

“As a gay man and a historian of infectious disease,” writes Downs, “I know about the harm that comes when public policy becomes infused with homophobia. Yet protecting gay men from discrimination and stigmatization today does not require public-health officials to tiptoe around how monkeypox is currently being transmitted.”

They aren’t tiptoeing. It is widely published that over 90 percent of the transmission of monkeypox outside of the endemic region is through sexual contact. Queer community leaders, organizations, and peer networks are the best and trusted sources of sensitive information about sex and risk; not everything must be on Twitter or in a PDF from the CDC signed with a drop of Rochelle Walensky’s tears. I’m not surprised that Downs may not be fully tapped into the peer networks of Black trans women—neither am I! But I know that just because something isn’t on my radar doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

Dr. Downs mentions MPV “prevention,” testing, and treatment only in reference to racial disparities in information about HIV: “The framing of the public-health crisis as predominantly affecting white men … eventually contributed to high rates of infection among Black men, who lacked equal access to information about prevention, testing, and treatment” (emphasis mine). Remarkably, he goes on: “This history should remind us that gay men are not a monolith; that race, class, and even region affect who has access to information; and that the lack of forthright information about how a virus spreads can lead to devastating health consequences.”

To imagine Black people lack access to only information and not healthcare is patronizing and refuted by decades of research. It’s beyond well established that healthcare insurance rates, for example, differ by race. Decades of research demonstrate why Black people may not trust healthcare providers, but this is different from—indeed in opposition to—a lack of information.

As I cited above, Black queer+ men have lower rates of behaviors associated with HIV risk, and higher rates of infection. But of those eligible for PrEP (including queer+ men and trans folks), only 8 percent of Black people and 14 percent of Latinx people have access, compared to 63 percent of white people. Research shows affirming healthcare and good health insurance remain key barriers for Black queer+ people. Perhaps behaviors and information aren’t the primary issue in need of intervention.

In New York, Black and Brown people make up the majority of MPV cases. In North Carolina, the first city or state to release racial demographics of vaccination, 19 percent of MPV cases are in white people, who received 67 percent of vaccinations; 70 percent of the cases are in Black people, who received 24 percent of vaccinations. “Prevention” is not defined by Downs, and could either be behavioral or biomedical, by vaccination, but we certainly know which of these he discusses at length in his writing.

Dr. Downs later claims that we have no evidence of whether closing New York’s bathhouses in the 1980s was an effective HIV preventative because careful epidemiology on the question couldn’t be funded. I find it odd that Downs would mention this policy, and the person who enacted it—Mayor Ed Koch—without acknowledging that Mayor Koch was a closeted gay man trying actively to hide his own sex life. That fact, omitted entirely, is certainly essential historical context about this matter.

More modern epidemiology shows that closing bathhouses actually doesn’t change or can even increase the rates of HIV transmission, because then sex just moves to private homes. This may seem counterintuitive to people outside of public health and those who are unfamiliar with these spaces, where you can get tested for HIV, get information about PrEP (ads over the urinals are particularly effective), or get a meningitis or MPV vaccine, all capable of preventing infectious disease. Reporting from the New York Times shows that vaccinating for meningitis, including at bathhouses, “haulted” an outbreak of that disease, which would have been impossible if people were having sex in private homes. Many fields, including epidemiology, can produce counterintuitive findings, which is why expertise or at least curiosity is so important.

Further, Dr. Tony Fauci talks explicitly about doing the very epidemiology Downs suggests didn’t occur: going to bathhouses in the early 1980s to see what behaviors exist and are changing. Fauci told The Advocate that it was “the epidemiologist in him” that sent him there. Maybe Downs, a historian, doesn’t consider this epidemiology sufficiently “rigorous”? Or maybe it’s simply because it doesn’t address the post hoc question that concerned him?

“But some agencies have become so wary about advising sexual abstinence of any sort that they won’t even tell men with symptomatic monkeypox infections to avoid sex for a few weeks until they recover,” Downs opines. “Officials in New York and elsewhere have suggested, as a harm-reduction measure, that sufferers cover up their lesions during sexual activity.”

That agencies don’t tell people to isolate when they have MPV is just untrue. The CDC recommends exactly that those who test positive for MPV should isolate at home. CDC materials specifically says, “If you or a partner has monkeypox or think you may have monkeypox, the best way to protect yourself and others is to avoid sex of any kind (oral, anal, vaginal) … while you are sick.” The CDC and WHO recommend condom use for weeks after recovery.

Downs is either ignorant of the difference between guidance and harm reduction, or is willfully misconstruing them to make a point; the article he links to in support of “agencies… won’t tell men with symptomatic monkeypox infections to avoid sex for a few weeks” is a report from the New York Times describing a disgruntled public health official who compared sex to bowling and set up an odd website to tell his side of the story. But even this official’s excerpt from the internal email that so angered him starts, “In addition to vaccine, prevention measures offer protection. These include avoiding close physical contact if sick, especially if there is a new or unexpected rash or sore.”

Downs might argue that it’s acceptable, even necessary, to focus so tightly on sexual behaviors (as opposed to, say, vaccine access and equity), as around 90 percent of monkeypox cases outside the endemic region are linked to sex. However, sex is a fact of life; it will occur, whether Downs and Ryan like it or not. We do indeed need to suggest risk and harm reduction for a time. But to focus so entirely on sex without even once mentioning access to interventions, to write about bathhouses as though people don’t find healthy joy there, to misconstrue or misrepresent public health guidance around risk reduction and the historical legacy of HIV/AIDS activism, is to harm those already ill, dismissing them as sluts who deserve it. Like Ryan’s article, Downs’s piece fails to mention the words “vaccine” or “Jynneos.”

This is not theoretical for me. My sick friend felt like he deserved to be ill. Do you know how many people I’ve texted over the last months: “And how’s your pain today?” This is not my only close friend who’s suffered. For two weeks in July and August, I had one or two people reach out to me every day for help getting testing or treatment for MPV, or help getting a vaccine post-exposure. These are my friends; this is my community.

I’m writing about this friend with his enthusiastic permission because he bravely decided that anything to reduce the sex-negative stigma of this infection is worth doing, even if it’s scary. Articles like Downs’s and Ryan’s apply this stigma: If you just didn’t have sex you wouldn’t have gotten sick—can’t you just abstain until MPV “abates”? My friend is scared. So, on the roof of The Eagle, I grab his arm. I put my hand around his back. I am infectious with touch. I bubble inside with delight. I’m a little drunk. I take a hit of poppers. I kiss another boy softly on the lips, not sexual, just friendly. I look up at the sky, so grateful that I’m queer—so grateful for one shot of vaccine even now in my body.

I leave The Eagle an hour later. There’s no sex, not even a little, in any of the nooks and crannies. I smile a sad smile; I miss it! But I know that the message of harm reduction that Dr. Downs, Mr. Ryan, and I all share has gotten out. Early data indicate that cases are now falling in New York. Because of the MPV incubation period, this behavioral change happened before either article was published. People were already protecting themselves and each other. The only difference between me and these two writers is that I believe that how you talk to people matters. Sex is healthy. You can provide information, risk reduction practices, and a timeline back to pleasure.

We still don’t know how effective the MPV vaccines will be, and we don’t understand how many people need to be vaccinated for transmission to decrease. We may well have to continue to care for ourselves through activism to get global access to biomedicine and through risk mitigation for some time. As I write in Virology: It’s too much to ask of us—but what choice do we have but to do it?