State legislatures have introduced nearly 150 bills this year limiting what teachers can say in their classrooms. A closer look at the world producing these bills reveals its ties to a forgotten and dangerous history.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

On Aug. 19, the first day of classes at a high school in Norman, Oklahoma, Summer Boismier showed students a QR code. The code provided access to the Brooklyn Public Library—yes, Brooklyn, New York, almost 1,500 miles away from Norman. Boismier provided students with Brooklyn library access so they could find books not welcome in her classroom under H.B. 1775, which limits what Oklahoma teachers can say involving gender and race. Boismier’s district had told her to hide classroom books potentially in violation of the law, which she did, but added a note declaring: “Books the state doesn’t want you to read.” Days later, after a parent complaint and meeting with school administrators, Boismier resigned, telling CNN the law made it “impossible for teachers to do their jobs.”

A few days earlier, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced his “Education Agenda Tour” to endorse school board candidates across the state who supported his plans of “[keeping] woke gender ideology out of schools” and “[rejecting] the use of critical race theory,” among other things. When Florida voters went to the polls, they elected 19 of the 30 candidates he backed and sent another six into run-offs.

A few weeks before that, I debated whether to include on my college writing class’s syllabus an essay about police brutality by the late writer, educator, and activist June Jordan. It’s a great essay, one I used to teach a lot. But in 2022, assigning an essay on systematic racism by a Black, bisexual woman felt, well, risky.

As of Sept. 26, state legislatures have introduced 140 bills this year alone that aim to limit what educators can teach in their classrooms about race, gender, and sexuality. Because I teach at a college, most of these bills, which overwhelmingly focus on K-12 classrooms, don’t directly affect me. But K-12 teachers in the 30 states that have introduced such bills or already made them law aren’t so lucky. And all teachers, myself included, receive a clear message when a bill gets introduced in any state: The government is coming for our curriculums.

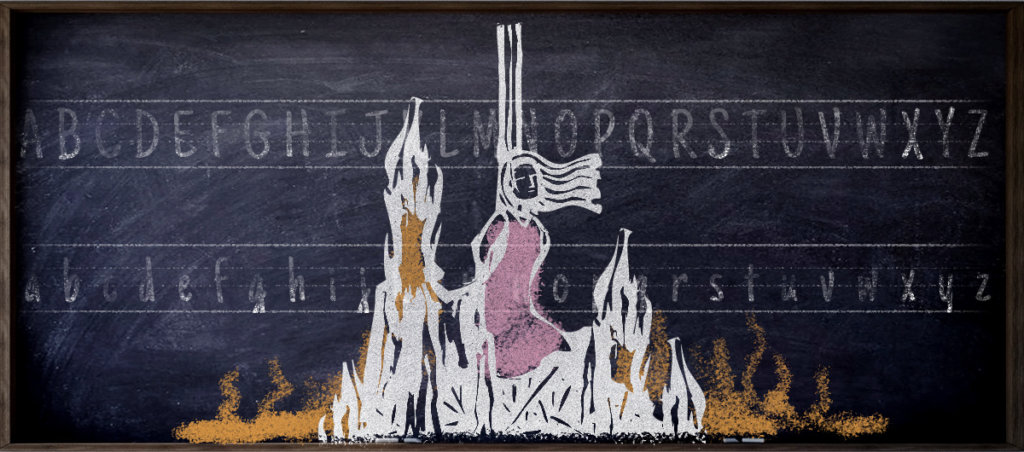

These bills have been rightly criticized for their racist and homophobic aims. But as an educator, I can’t help but wonder if we’re missing part of the story: Is this a witch hunt for teachers?

If that connection feels flimsy or even melodramatic, that’s probably because today the term “witch hunt” is so pervasively, almost comically misused that we’ve forgotten what it means. And you know what they say about those who don’t learn their history: They’re doomed to repeat it.

The witch hunts, as several historians kindly but frequently reminded me, are complicated. They spanned centuries and continents; their specific details depended on the year, region, or quality of crops a growing season yielded. Still, there are telling facts about this complicated history that most everyone agrees on.

The witch hunts took place from around 1450 to 1750, but their heyday was the mid-16th to the mid-17th centuries. This means they weren’t products of the oft-presumed unsophisticated Middle or Dark Ages. They were at their height during both the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution. As Suzanne LaVere, a historian and interim director of the women’s studies program at the University of Purdue Fort Wayne put it, “At the same time you have the Renaissance writers in Italy…” (think Leonardo DeVinci and Michelangelo) “…you have the Catholic Church in Italy increasing the number of people they try for witchcraft. These things are existing side by side.”

That’s because while society was making progressive steps forward in some ways, in a whole lot of others, it was falling apart. (Sound familiar?)

One big reason society fell apart in tandem with the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution was the Reformation. The Reformation started on Oct. 31, 1517, when Martin Luther published his 95 Theses, and it led to about 150 years of conflict and sometimes literal war between everyone from neighbors to state and religious leaders of Catholic and Protestant faiths, explained Michelle Brock, a historian and professor at Washington and Lee University. Life was, she said, “a hot mess,” adding, “There [was] just a tremendous amount of social and political upheaval.” The Reformation also brought increased attention to the question of what it meant to be “a good Christian,” said Arianne Sedef Urus, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania. Since witches were understood to have made deals with the devil, getting rid of them was important to both Catholics and Protestants in winning the battle of good versus evil.

To recap, historically, witch hunts occurred when societal advancement clashed with social anxiety and political turmoil, a description that feels similar to the hot-mess environment that’s unleashed these education bills. Not everything is moving backward: Our vice president is the daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants, and young Black girls will soon have a Little Mermaid who looks like them. But also, we generally don’t trust our government and don’t like each other. We’re more stressed than ever because of inflation, COVID, and the war in Ukraine. And some people really hate that Black mermaid.

And just like the witch hunts involved religious struggle, we’re very much dealing with a religious struggle of our own, said Sarah Marshall, host of the podcast You’re Wrong About. “One of the things that is nakedly obvious is that we live in a society divided between secular culture and religious culture … primarily American Christianity,” Marshall explained. From Ronald Regan’s Religious Right to Marjorie Taylor Greene’s desire for the GOP to be the “party of Christian nationalism,” Republicans have chosen their side. The fact it’s Republicans pushing education bills that stifle LQBTQ+- and sex-education specifically—familiar foes of that Christian Right—makes American classrooms a religious battleground. By daring to teach students about sex and gender identity, teachers become a 21st century witch, a secular enemy in a struggle to establish religious education in schools.

When societal revolution and reality meet

The invention of the printing press in 1436 also shares blame in furthering the witch hunts. With the new technology, books like the Malleus Maleficarum, a how-to manual for punishing suspected witches, reached audiences like never before. First published in 1487, Malleus Maleficarum was republished “upward of 15 times, [selling] around 30,000 copies throughout Europe during the great witch-hunts,” journalist Mona Chollet writes in the 2022 translation of her book In Defense of Witches. Pamphlets circulating stories about witch trials from other areas could also now be pumped out and passed around, LaVere added, building on their lore. The printing press allowed information to spread “at a bigger level than it was before in a way that perhaps we weren’t prepared to deal with,” LaVere said. “Information explodes but so does misinformation.”

And, well, you know where this is going, right? We’re again living with new technology that produces information and disinformation at a rate we can’t control. And one of many consequences of that misinformation is parents convinced that the bigger threat facing children in school is books with non-white characters written by non-white authors, and not, say, gun violence.

Unless you are Woody Allen, Harvey Weinstein, Brett Kavanaugh, or Donald Trump, you likely know the witch hunts primarily affected women. Roughly 70 to 80 percent of the witch hunts’ victims were women, depending on which historian you ask. Still, they’re often considered a “gender-related [but not a] gender-specific crime,” Brock said. Women ended up being the witches, I was told, because women were viewed as more susceptible to Satan’s influence (Thanks, Eve); because women didn’t have identities wrapped up in stuff like jobs, so if someone lobed the w-word their way, the reputational damage was brutal; and because, sure, after you execute a whole bunch of witches who are women, you start thinking that’s what witches look like, and what you do know, the other witches you find end up being women, too.

In other words, the system was set up in such a fundamentally sexist way that women were destined to be disproportionately accused of being witches.

The K-12 teachers impacted by these education bills are also predominantly female. According to federal data from 2020, 80 percent of K-12 teachers are women. And that’s not a coincidence. Before the Civil War, teachers were mostly men, said Kate Rousmaniere, an education historian and professor at Miami University of Ohio. But after the Civil War, she said, we had a lot of dead men and single or widowed women, plus a desire to expand our public school system—a goal that needed cheap labor. It was also around this time that ideas about education being a “caring occupation” came into play, Rousmaniere added. And, come on, when you’re looking for cheap caregivers, what you’re really asking for is women. By 1900, the majority of K-12 teachers were female, and the profession basically never looked back. (It has the pay to prove it.)

In other words, the system was set up in such a fundamentally sexist way that women were destined to be the vast majority of K-12 teachers targeted by the onslaught of education bills.

The legacy of the witch hunt

I guess you could say, we’ve done it again. When we needed a scapegoat, for our religious anxieties, for our changing world, for whatever it was we were scared of or angry at or didn’t understand, consciously or not, we zeroed in on the women. That, to me, is the principle lesson and legacy of the witch hunts that society can’t seem to shake.

Or at least, I thought this was the principle lesson and legacy for me. Then I spoke with Sedef Urus, who made me reconsider these events all over again.

“There’s been a revival of a lot of women—a lot of white women—saying things like, ‘I’m a witch,’ … and associating being a witch with a particular brand of feminism, [thinking they’re going] against the patriarchy and harkening back to these women who were executed,” Sedef Urus said.

As she spoke, that line, We are the granddaughters of the witches you could not burn, flashed in my mind. The one I’ve seen written on signs at protests and printed all over Etsy merch the last few years. “What I just want to say,” Sedef Urus continued, “is that none of these women who were accused of witchcraft and executed for it would have self-identified as a witch [even if they confessed to it.] … Perhaps it’s cool to think these women were witches in the 21st century, but it’s very ahistorical.”

There is, of course, a long history of groups reclaiming words once used against them, something many women have done with “bitch.” Still, Sedef Urus has a point.

If the women killed for being witches never identified as such, then their legacy shouldn’t be that of radical martyrs who died challenging the system. They died because it was easier for people to blame them than to understand the challenges of their time. They died because the world was capable of believing something inside these women was so dangerous, we had to get rid of them.

I hope the legacy of these teaching bills isn’t distorted in this same way as the witch hunts. I hope centuries from now, feminists don’t take to the streets proclaiming themselves descendants of the educators we could not silence, eager to carry on our radical agendas. I don’t want that because I don’t think I have a radical agenda. And I don’t think Summer Boismier in Norman, Oklahoma, or other teachers do, either. What I —what we—want to do is tell the truth. About what love looks like, what people and families look like. About the history of this country and the people we’ve hurt while building it.

It’s a fear of that truth, I think, that’s fueling these bills. A fear of how that truth might force us to alter our understanding of the challenges of our time. A fear that inside of that truth is something so powerful—maybe even so dangerous—we have to get rid of it.