In this life-affirming conversation, veterinary oncologist Dr. Renée Alsarraf talks with DAME about caring for dogs with cancer—including her own beloved pup, whose diagnosis coincided with her own.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

The great Gilda Radner once said she saw dogs as “the role model for being alive.” Veterinary oncologist Renée Alsarraf would agree: In her three decades as a veterinary oncologist, the New Jersey–based Alsarraf has guided countless dogs through cancer treatment, watching them bounce through the clinic door and wag their way through invasive treatment procedures without a care in the world. And when Alsarraf was herself diagnosed with cancer at age 51, she realized that managing her own fear, anxiety, guilt, and self-doubt might require a less, well, human attitude.

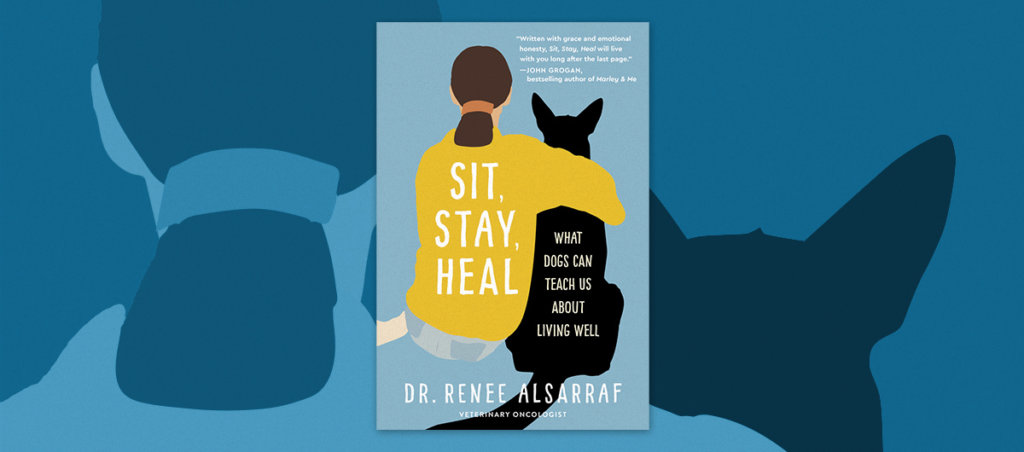

In Sit, Stay, Heal: What Dogs Can Teach Us About Living Well, Alsarraf (whose cancer is now in remission) recalls the dogs whose illnesses—and, in some cases, improbable longevity—prompted her to extend the optimism and empathy of her clinical practice to her own experience of cancer. From a cocker spaniel in an Elsa dress to a decorated police scent hound to a mobster’s beloved German shepherd, they are reminders of how much dogs and humans give to, and get from, one another.

DAME: You write early on in Sit Stay Heal that “dogs wear collars and are put on leashes, but we humans are the ones who feel the restraints of our own insecurities, our own what-ifs, our own doubts about self-worth.” One of the book’s through lines is the difference between how humans respond to sickness in animals and how we respond to sickness in ourselves. Was that something you thought about prior to your own illness?

Renée Alsaraff: The only thing I had thought about prior to my own illness is just the difference in our makeup. If you’ve ever known a woman who’s had a hysterectomy, she’s bent over, she’s shuffling when she’s walking, she isn’t allowed to drive for a few weeks. If a female dog is spayed, the next day she’s in the backyard chasing a squirrel. Dogs tend to be hardier, physically, as patients.

And we—or at least I—got so nervous before my appointments, with those what-ifs. I think that [those] just serve to hurt us, to bring us down. It’s a waste of energy. Dogs don’t have that preconceived doom. You know, I might leave the hospital after chemotherapy and think, Why did it take the nurse two tries to put the catheter in? Or, Is my hair going to fall out? But dogs are up off the table, wagging and ready for a biscuit. And I think that mental outlook is something that we could learn from them.

DAME: You joke in the book that cancer treatment might be easier to face if, like dogs, we got treats for showing up to appointments. I’d be curious to know if you had any revelations about what human healthcare systems can learn from treating animals, especially around long-term illness and the uncertainties around them.

RA: Human health care has a lot more research money and more knowledge about a lot of things. Then again, insurance companies often dictate not just pricing but treatment protocols. As veterinarians, we’re freer to offer different options, and often more able to think outside the box just for everyday care. I give families a multitude of options—we can do full chemotherapy, or half-body, or no chemotherapy—and go over all the risks and the side effects and the prognoses. Knowledge is power, so the best thing I can do is inform that pet family, so they can make a decision for their pet and for themselves. Hopefully, pet families feel like they have a lot of control, so that they don’t have regrets. But as human patients, we’re often not a part of that medical decision-making process. None of that feels like it’s in our control.

In veterinary oncology, we also tell families what the odds are: the percent of pets that will go into remission, and for how long. In human medicine, it was my experience that none of my doctors ever shared that information. And I pushed them on it a bit, and was told that it doesn’t really matter. Whether you’re in that 10 percent who does really poorly with treatment, or you’re the 20 percent who does great, you’re just one person. I assume doctors don’t want to tell you the odds because they don’t want to get you down. But I am someone who would like to have that knowledge.

Human medicine is so specialized, so there’s a tremendous amount of knowledge and advancements. But I think at times the patient doesn’t feel wholly cared for. Whereas as a veterinarian, even as veterinary specialists, we treat not just the whole patient, we treat the whole family, and we tend to honor the family dynamic.

DAME: Your dog Newton got cancer at the same time you did. Did you ever feel that you and he were meant to share that experience, terrible as it was?

RA: Some people actually offered that [idea] up. But it wasn’t easy. In the beginning, when he was kicking butt and doing great with treatment, it was great to see how much he not only felt good and flourished, but how much he enjoyed his days. Where it became really hard was at the end. I didn’t have survivor’s guilt, but I did have a tremendous amount of remorse; I wondered, you know, Did I do everything possible for him? Which I did, but you still ask yourself that, not just as the pet parent but as the vet taking care of him. You always think your dog is going to be by your side to do all the fun things; I never thought he’d be by my side for [cancer]. And in the end, I was the only one of us that survived that. And that added to my sadness after he passed.

DAME: Most of us know the health benefits of having a dog: They can lower our blood pressure, get us moving and out in nature, encourage us to live more in the present. But we also ascribe a kind of humanity to them, a sense that they truly understand how we’re feeling and respond accordingly. Is that real?

RA: Being a veterinarian for more than 30 years and getting that front-row seat to all the families that would tell me their stories and to see those dogs, I firmly believe that it is real. Take, for instance, that first chapter with Daisy, the cocker spaniel. That dog had no training whatsoever, but became a seizure-alert therapy dog for a family with a special-needs child. [Or] the next chapter, with Bentley the beagle: When [his owner] was walking slowly, it wasn’t like Bentley first pulled ahead and then realized the man was walking slower—he just took his cues from the man. I do think on some level dogs are wise in ways that we are not.

DAME: What’s the one thing you want readers to take away from your experience, both as a cancer patient and as a veterinary oncologist?

RA: I think the big takeaway is that dogs are such a source of comfort and guidance to people who are struggling, whether it’s [cancer] or something else. We all have these big, sometimes insurmountable struggles, and I hope the book shows the enormous power that the human-animal bond plays in our healing. I hope it validates the struggles we all go through and [reminds us] that we can make it out the other side and be better off along the way.

Read an exclusive excerpt from Sit, Stay, Heal

When I was first told of my cancer diagnosis, I felt like someone had pulled the rug out from under me. I still feel that way, and it’s an empty, horrifying feeling. I replay that day over and over in my head.

It was 7 p.m., July 3. It had been a long, busy day at the veterinary clinic, and I hadn’t had time to change after arriving home, so I was still sporting a navy blue sleeveless dress that zipped up in the back, with white dog hairs clinging around my hem. I took the call, then sat down on the steps into the kitchen and hung my head. We were getting ready to host 17 adults and eight kids for a big Fourth of July celebration the next day, and I had stockpiled uncooked hamburgers and hot dogs in the refrigerator. My mind raced yet seemed blank at the same time. I tried hard to stifle the flood of emotions, but they still rushed to the surface, a loud cacophony in my head.

Oddly enough, for someone who typically has no problems sharing her feelings, I had a hard time sorting these out. One of my first thoughts was what a waste it had been, saving all that money for my retirement. I told my husband that since I couldn’t take it with me, I needed to go to the mall for a little shopping. Or maybe a lot of shopping. He didn’t think that was funny. I thought it was hilarious.

I then went straight to worrying about terrible side effects, and how ultimately all this would affect my family. Even though my son was still in high school, the sadness struck me that I would not live to a really ripe old age to be a bother to him and his future family. I’d never felt so vulnerable, so aware that things like this can just happen. Which fed into worries about all the “what ifs.” I am tough enough to weather a storm, but I’m not so sure about a monsoon, followed by an earthquake, followed by fire from heaven.

We canceled the celebration. We couldn’t see past this news to realize that we still had things worth celebrating. I thought of my patients—dogs and cats are so lucky not to have the capacity for worry that we humans (or I) so acutely possess. My dog would have gone ahead with the party with his friends and enjoyed himself—especially with all that ground beef and those hot dogs on offer. Instead, I was left with a bunch of food that I wound up giving away, lest it go to waste. We spent a somber Fourth, when we could have been surrounded by those we love and who love us.

I am anything but joyful as I open the door to the human cancer center. My canine patients are typically happy to see the staff as they get to the clinic. They wag their tails in anticipation as they walk through the door, hopeful for a biscuit. No one at the center has ever offered me a piece of Godiva chocolate, although maybe this would be a good trend to start. Frankly, I’m terrified as I head into the elevator and push the button for floor No. 6. My thoughts are loud, crowding my head. How will I look after going through therapy? What will people think? I know these are superficial concerns, but they still feel crippling. Dogs wear collars, and are put on leashes, but we humans are the ones who feel the restraints of our own insecurities, our own “what ifs,” our own doubts about self-worth. But worthiness doesn’t have prerequisites.

Fear does not weaken my will; nor my resolve. I hold my head up high and state my name. I am meeting with the medical oncologist to find out what the plan of attack will be. I will gear up for this fight and bring whatever is needed into battle. I am recovering from uterine surgery that I had immediately after my initial diagnosis, and thankfully am healing without complications. I quickly learn that one surgery can cause me to walk like my 81-year-old father, though it took him 81 years to develop that slightly bent-over shuffle. Don’t get me wrong, I love my dad—I’m just not ready to walk like him.

Unfortunately, despite a favorable pathology report, with a 3-mm. metastatic lesion (spread) in my peritoneum (lower abdomen), my doctor tells me that I will need both chemotherapy and radiation therapy to combat the carcinoma. I have appointments with two other doctors coming up in the next week or so. Until then, I will not have a full plan. The likelihood is that, once I am fully healed from surgery, I will need five and a half weeks of radiation therapy and numerous rounds of chemo. This will run over the course of many months. Turns out I am really, really vain—it upsets me a lot that I will lose my hair.

Dogs and cats don’t lose their fur when they receive chemotherapy. That’s because, in general, an animal’s hair pattern is much different from a human’s. Do you ever have to take kitty to the barber because his fur grew too long? No; the majority of animals’ fur grows to a certain point and then stops. It sits there in a quiescent stage, whereas our hair grows and grows and grows. Chemotherapy targets the fastest-growing cells; hence our hair is often a goner from treatment. Not so with pets. The exception is dogs that are good for people with allergies, like poodles. Their fur follicles are more like a person’s hair in that they continue to grow, so these kinds of breeds can suffer fur loss.

Losing my hair is nothing compared to the loss of my life, but I bristle at the implications. If I lose my hair, I will look like a C word patient. I never want to show my enemy my weakness, and that includes what grows, or doesn’t grow, on my head. When threatened, some dogs can raise their hackles, which makes their hair stand out to give them the appearance of the biggest opponent that they can be. I want to deny that the C word has gotten the best of me. I want to be the biggest opponent I can be. But maybe this is like trying to defy gravity. At best, it seems like false bravado.

What floors me is how many random strangers without the C word have told me what to do without being asked. It’s like when a stranger comes up to a pregnant woman, touches her enlarged belly, and then proceeds to give the mom-to-be unsolicited advice: How to raise the child. What to name the child.

I was told that I should just shave my hair in advance, even though it is just fine now. First of all, I’ve never liked being “told” what to do. Secondly, really?! For me, that would be a sign of giving up, and I fight as a matter of principle. I will be the one who goes down with the ship, or at least knows when to man the lifeboats. Perhaps that’s a good quality to look for in an oncologist, whether for humans or for animals.

From SIT, STAY, HEAL by Renée Alsarraf and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2022. You can purchase the book here.