One in five women experience intense physical pain from sexual intercourse, which often goes untreated for many reasons—not least of all due to the shame women are made to feel for seeking pleasure.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I lost my virginity at the ripe old age of 26.

I’d grown up believing I would save myself for marriage, but I’d left that mindset behind after college, when I quit the evangelical church and started at a mainline Protestant congregation where no one cared if you drank or had sex. After abandoning evangelicalism, it took a while to find the right person with whom to embark on this new adventure. At 26, the idea of sex had developed such an aura of mystery and heat and intoxication for me that I wanted to have it with someone I really liked.

So one September night, I tagged along with friends to attend an open mic in a fog-soaked corner of San Francisco. A lanky comedian in worn jeans took the stage, with humor so weird and cheeky and rapid-fire, I thought he’d wandered off the set of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. I liked him immediately. His name was Blake. We started dating.

At the time, I was living in Reno, Nevada, and working for an alternative weekly newspaper. Blake lived in the Bay Area so we started seeing each other on weekends, taking turns driving over the Sierra Nevada mountain pass in the dead of winter. Come February, I was ready. Blake and I started making out in the dank, carpeted bedroom of the Oakland flat he shared with three slam poets. I was turned on, I was wet. But the moment Blake entered me that bright winter afternoon, I had to bite my lip, the pain was so sharp—lacerating. I don’t think Blake realized what was happening inside of me. After it was over, he cracked a dumb joke—I think he was trying to lighten the mood to make sex less awkward. Normally, I would have laughed. Instead, I started bawling. I wondered, was it Blake, or was it me?

Four years after we first got together, Blake and I split up, I started dating again. It clarified things: Sex with other men hurt, too.

Nobody talks about painful sex. At least, that’s how it felt to me after Blake and I started sleeping together. My male and female friends seemed to get it on like it was the simplest thing in the world. “It wouldn’t have hurt if you’d done it with me,” one male friend joked. In every movie I’ve ever seen, female characters tear off their clothes and start groaning with desire after like three seconds of foreplay or, in the worst-case scenario, they lay beneath the guy looking stoic and bored. What was wrong with me? Why did it hurt so much?

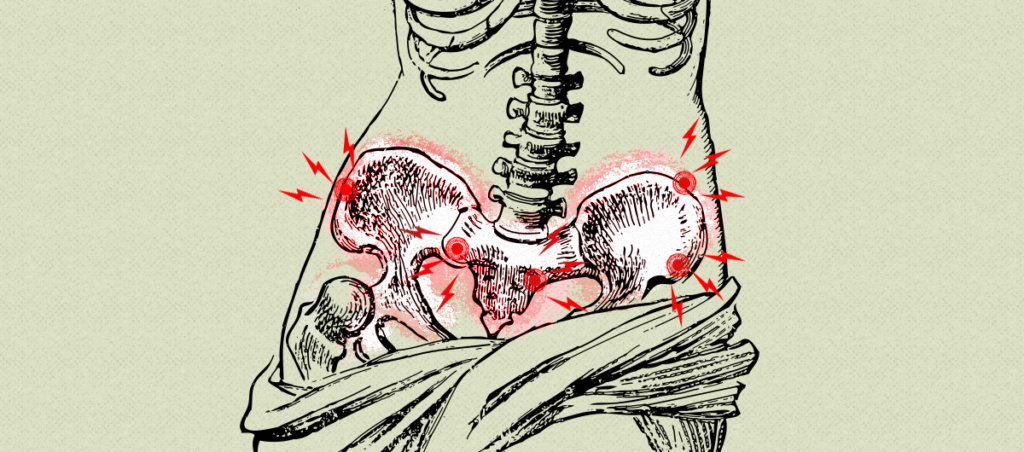

Sex can be physically painful for a number of very real physiological reasons, among them, endometriosis, hypertonic pelvic floor muscles, an infection like bacterial vaginosis, vulvodynia, and the bladder syndrome, interstitial cystitis. But many doctors have received little to no training in medical school about sexual pain, or dyspareunia, despite the fact that as many as 18 percent of women—and 5 percent of men—experience it at some point in their lives. “To a shocking extent, doctors simply don’t know about sexual pain: how it starts, how it worsens, how to treat it,” assert the authors of Healing Painful Sex, Deborah Coady, M.D., and Nancy Fish, MSW/MPH. “Women who suffer from sexual pain feel isolated and confused in a way that’s like no other we’ve ever seen.”

A number of barriers can prevent people with vulvas and vaginas from obtaining the right medical care, Jill Krapf, M.D., co-author of the book When Sex Hurts: Understanding and Healing Pelvic Pain, told me. These barriers include “lack of time in doctors’ appointments, lack of training and experience on the part of practitioners in diagnosing and treating chronic vulvovaginal pain conditions, and reluctance of patients to bring up these concerns related to embarrassment, believing their doctor is not interested, or thinking there are no treatment options.”

It’s not unusual for doctors to dismiss women’s concerns as being psychological. “Talking about sexual pain with your doctor can sometimes make you feel even worse than keeping silent,” write Coady and Fish. “If you’ve tried to speak with a physician about your condition, you may already have been told—perhaps several times—that your problem is ‘all in your head,’ that it stems from your bad attitude toward sex, or that there’s nothing that can be done to help you.”

Even as my sexual pain persisted, I did not see a doctor about it. I thought the condition was shame-induced, owing to my evangelical upbringing: I’d been raised to believe that premarital sex was “like dirt in God’s eyes,” as one female church leader in my life explained it to me. Even marital sex seemed vaguely polluted. Yet the church’s anti-sex hysteria was nothing compared to my mother’s. My mother, a victim of adolescent sexual trauma, hated being alone in a room with a man who wasn’t my quiet, gentle father. When I was 11, I converted a knee-length acid-washed jean skirt into a mini-skirt; my mom took one look at me and said I looked like a streetwalker. She shushed anyone who spoke about sex in my presence, even when I was well into my teens. Three years after my breakup with Blake, at 33, I met Daniel.

Daniel was kind and funny and handsome—and enigmatic in the best way possible. He’d spent years hitchhiking around the U.S. and had a long rap sheet for activist stuff like feeding soup to the homeless without a license. Around him, I felt at once energized and at ease. We had sex on our fourth date. I expected it to hurt, but to my shock, it felt … amazing. I thought, Maybe it was true, I just hadn’t met the right guy!

But after a year, sex started to hurt again. This time, I consulted my OB/GYN. Since sex had felt good for a year, I knew there was more to what I was feeling than merely shame. Eventually, I was diagnosed with pudendal neuralgia—chronic pain of the pelvic nerve that innervates sexual, bowel, and bladder function..

By this point, the neuralgia had worsened to the point where it hurt to sit. I was enrolled in a graduate program in comparative literature. Sitting for long periods on hard wooden seats for my long seminars caused excruciating vaginal pain.

I began working with a pelvic floor physical therapist, who suspected the neuralgia had been caused by long-distance cycling. A year earlier, I’d done a thousand-mile bike tour down the California coast. I regularly did five-mile rides in the Berkeley hills, and occasionally biked 20- to 50-mile stretches around the Bay Area. Hard saddles, combined with the forward-tilting posture one assumes on a road bike, can cause compression injuries.

But was long-distance cycling really the culprit? The neuralgia felt more like the return of an old curse.

Illness can feel like a verdict on one’s very existence, especially when symptoms are not so clear cut. “Initially, [my] illness seemed to be a condition that signified something deeply wrong with me—illness as a kind of semaphore,” Meghan O’Rourke writes in The Invisible Kingdom. One can’t help but ask, Who am I, that my body can betray me like this? What happened to the person I used to be? Why did I get better, and then get worse again? At 26, my dyspareunia had felt like an accusation, as if my body were taunting me—How dare you have pleasure? When the neuralgia hit at 34, I slipped back into this old way of thinking. The pain felt like it was my fault, though I couldn’t quite pinpoint what I’d done wrong.

The word pain comes from the Latin poena, punishment. It was only later that poena came to mean grief; notions of sensation attached later still, according to Lisa Olstein in Pain Studies. On my worst days, it felt like a vulture was trying to claw its way out of my vagina, or as if I had a shard of glass in there and someone was using it to tear my body up.

It was a year into the neuralgia when I learned pudendum, from the Latin, means that of which one ought to be ashamed. Of course, I thought when I read this. There’s the old curse.

But the more I learned about pudendal neuralgia, the clearer it became to me that mine did indeed stem from the cycling I’d done at 32 and 33, long after I’d split with Blake. In other words, this new pain probably had nothing to do with the dyspareunia I experienced in my mid-20s and early 30s. Eventually, a specialist in Arizona told me I’d probably need surgery to decompress the nerve. At this point, I’d lived with the neuralgia for several years, managing symptoms through a combination of physical therapy, rest, avoiding sitting, and body-mind psychotherapy. I’d assumed the nerve was just irritated. Then, after a particularly bad flare, I consulted the Arizona doctor, who said the nerve was probably entrapped in scar tissue.

Why did it take so long to get to the root of the problem? No accurate test exists to determine whether the pudendal nerve is irritated versus compressed. But a doctor can deduce the existence of compression, a.k.a. entrapment, by taking a thorough patient history. Few doctors in the world are trained to do so. The Arizona specialist is one of just a handful of doctors worldwide who perform the surgery.

“Sexual pain conditions in people with vulvas and vaginas have not historically been well identified or treated adequately,” Krapf says. “Given the limitations in training on sexual pain conditions, it is important for patients to advocate for a diagnosis and focused treatment plan. Patients can learn more about their condition through information provided by support organizations such as the National Vulvodynia Association, Health Organization for Pudendal Education, or the Lichen Sclerosus Support Network.”

Like many women, mine is not a simple tale that follows the “typical” medical arc of diagnosis, treatment, and eventual cure or remedy. I still don’t know why sex hurt before I met Daniel. I do know pudendal nerve entrapment was to blame for the pain I’ve had the past decade. This year, I underwent decompression surgery with the Arizona specialist. He found a good deal of scar tissue compressing the nerve, and, fortunately, was able to surgically release the nerve. Recovery can take up to two years.

Sometimes, I find my mind slipping into the danger zone of “if only” thinking. If only someone had diagnosed the entrapment within the first year or two, I might have avoided complications of the entrapment, like the pain of walking and of wearing tight clothing that developed as the years passed. I feel like I’ve been gaslighted for years by people, including a physical therapist, who suggested the pain was psychological and that I needed to “retrain my brain.” Such an attitude can be used to excuse practitioners’ inability or lack of inclination to identify and treat the underlying causes of one’s symptoms.

And yet, I’m grateful to have finally found the medical help I needed, and proud of my persistence in finding a specialist who could diagnose me and prescribe the right treatment. I know and trust my body. The problem wasn’t having too much shame, or not finding the right position during sex, or even biking those thousands of miles. It has finally sunk in that none of this is my fault.