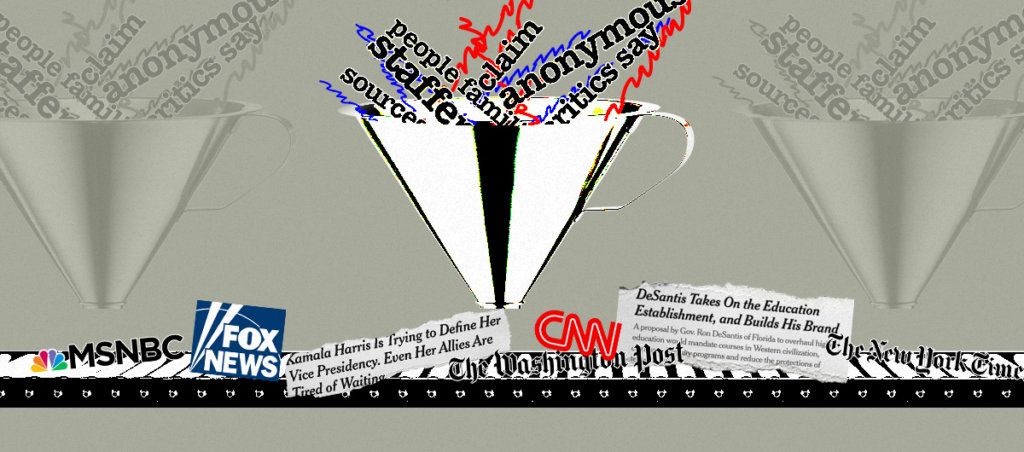

When a paper of record makes unsubstantiated claims, other media outlets see them and spin them out in a subversive game of telephone. Is this how we really want the first draft of history to be written?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Last week, the New York Times published a piece on Vice-President Kamala Harris that implied Democrats doubted her ability to lead the party and were worried about the way she did her job.

Through much of the fall, a quiet panic set in among key Democrats about what would happen if President Biden opted not to run for a second term. Most Democrats interviewed, who insisted on anonymity to avoid alienating the White House, said flatly that they did not think Ms. Harris could win the presidency in 2024. Some said the party’s biggest challenge would be finding a way to sideline her without inflaming key Democratic constituencies that would take offense.

Producers and editors picked the story for discussion on 24-hour cable networks, chatty news sites and blogs, with pundits weighing in, not on whether the story was accurate or fair, but whether Harris herself had what it took to be a skilled politician and president-in-waiting.

In the hours after the story went live on the Times site, media critics pointed out that despite its dire-sounding premise—Kamala Harris is on the ropes!—the story didn’t quote a single Democratic critic saying anything harsher than “Yeah, it’s rough being the first female anything.” And the story itself was about the substantive things VP Harris has been getting done, with no recognition or credit from the press.

That, readers, is how a political narrative gets written.

As we’ve seen over and over in cases of disinformation, debunkings and fact-checks can’t compete with this game of telephone, and in fact mostly add to it. If there isn’t any substance to the story, one could reasonably ask, why are we talking about it so much?

The story itself makes news, and the news is the story—a turducken of triviality and self-reinforcing inaccuracy. So now we’re debating whether the Vice-President is bungling, embattled, having a rough time of it because “some Democrats”—who and how many?—are having misgivings about how she’s perceived. Said perception, of course, being profoundly affected by the very coverage of the perception, in a conundrum that would baffle both chickens and eggs as to which came first.

Contrast that with the same newspaper’s coverage of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, as he “takes on the education establishment” and “builds his brand.” Well, DeSantis is taking on the “education establishment” by frightening teachers into hiding their school libraries and pictures of their spouses, and building “his brand” by flying frightened newcomers to the U.S. across the country against their will. But those facts apparently mattered less to the Times than the way the governor’s hate appeals to voters.

That was the critical issue the Times chose to highlight, with regard to DeSantis. With VP Harris, the newspaper platformed people who were upset that she flubbed some words in an interview.

The impact of each politician’s actions went unexamined, un-contrasted. Harris’s gaffes killed exactly nobody while DeSantis is signing bills to outlaw medical care for transgender people. The only thing that mattered, to report on, was the perception of each politician.

Truly objective journalism relies on clarity. Clarity about why certain stories are pursued, some with more resources than others. Clarity about how stories are placed and prioritized, picked up for discussion on TV news and talk-radio shows, given attention by editors and producers. Clarity about whose views are considered legitimate and whose are not. And too few news organizations provide that clarity.

Political reporters often scoff at the idea that they affect the way people form their opinions. After all, they just report on what people tell them, right? They’re not in charge of whether or not you believe what some governor or senator says. They’re just the messengers, and questioning them is tantamount to shooting them.

In fact, the Times particularly is known for reporters getting crabbily defensive when critics ask questions, implying that said critics don’t understand the tradecraft of journalism. Peter Baker, one of the authors of the disputed Harris piece above, has leapt to defend colleagues from any intimation of bias or mistake, particularly when those critics are liberals.

Second that. There's no reporter on the White House beat more professional and talented than @maggieNYT https://t.co/fM3XZ9VpDc

— Peter Baker (@peterbakernyt) May 28, 2018

But all the thin-skinned replies on Twitter in the world don’t answer for how easily manipulated the White House press room can be, and no one knows that better than right-wing media figures, who pride themselves on “flooding the zone with shit” and persuading reporters to chase nonsense stories like preschoolers on a soccer field.

A story gets published on a right-wing blog like The Daily Caller or Red State or The Daily Wire, or tweeted by some minor right-wing figure and discussed on Fox News. A Republican politician uses that Fox News story to push a line about whatever it is being a crisis. Reporters ask Democrats to respond to the Republican assertion, and then publish sober stories about the “firestorm of controversy” that “has erupted” all by itself.

We see this happen repeatedly: A caravan of migrants is about to invade America’s Southern border! Teachers are indoctrinating white students to feel bad about their skin through critical race theory! Big U.S. cities are being burned to the ground by criminals every night! Drag queens and trans people are threatening the innocence of children! College students are banning all political speech!

After weeks of commentary by everyone from Dr. Phil to Bill Maher to your mom’s hairdresser, it hardly matters that the stories aren’t even close to being true. There was never a gigantic migrant caravan; no elementary school on Earth teaches critical race theory; violent crime is at historic lows; drag queens are bothering no one; trans people just want to live their lives; and mild criticism of bad sandwiches hasn’t ruined higher ed as we know it.

Good luck convincing your mom and her hairdresser of that, though.

Countering these narratives requires more than just line-by-line dissections online after the fact. It requires a commitment to informing, rather than inflaming, one’s audience. It requires that journalism leaders root their stories about public officials in something more consequential than celebrity-style gossip and take responsibility for the perceptions they help to create.