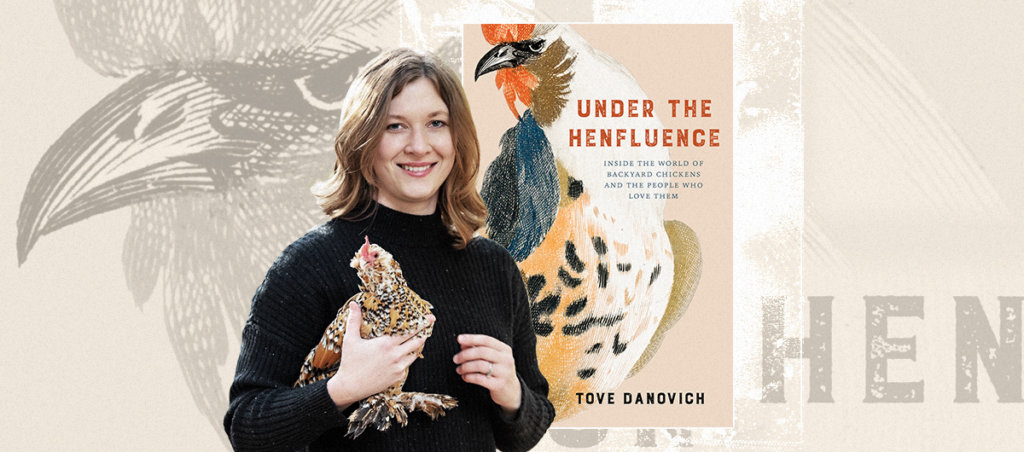

In this exclusive excerpt from Under the Henfluence, journalist and chicken-keeper Tove Danovich explains the domestication process of the tiny dinosaur.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When we domesticated wolves to turn them into the dogs that live in our homes (and sometimes sleep in our beds), we altered almost everything about them. We reduced their long, tapered snouts into the smushed faces of breeds like pugs and bulldogs. Some dogs are taller than the average man when they stand on their hind legs; others can fit into a handbag. Dog breeds developed the ability to raise their inner eyebrows, while wolves cannot. Their behavior changed too. They’ve evolved to see humans as teammates if not family. Studies have shown that when asked to solve a problem, dogs make eye contact with their humans as if to ask for help.

Obviously, chickens were domesticated for very different reasons than dogs. Fowl have been bred to have aesthetically appealing feather patterns, gain weight quickly, lay a lot of eggs, or lay eggs with various colors. The average domestic chicken looks very different from their wild cousins living in Asia. Red junglefowl typically have dark gray legs (not yellow), and the color white is minimal in wild junglefowl. They’re small and light, which makes it easy for them to fly to safe roosting spots. The process of domestication itself, which requires animals to lose their fear of humans, is where the change from junglefowl to chicken began. A group of researchers at Linköping University in Sweden bred red junglefowl for tameness and after only three generations found that the birds “grew larger, laid larger eggs, and generated larger offspring.” After a few more generations, the tamed junglefowl became less scared of new things and their gene expression began to change in notable ways from previous generations. The simple act of taming animals, not even breeding them for specific traits, changes their very genetics.

But on a fundamental level, domesticated and wild chickens are two sides of the same coin. Most domesticated chickens are just as smart and capable as chickens in the wild. Even their language is still similar—a wild rooster’s cock-a-doodle-doo, compared to a domestic chicken’s, sounds like the same word spoken with an accent. “People often assume that domestic animals are so badly maladapted that they’re only going to go feral one time in a million,” biologist Eben Gering tells me. “But that doesn’t really seem to be the case.”

We’re sitting on the patio of a coffee shop in Florida, where he currently teaches at Nova Southeastern University. He’s wearing a button-down shirt with a fish print on it and his practical shoes have colorful striped socks peeking out of them. Gering started studying feral chickens on Kauai with another evolutionary biologist, Dominic Wright, in 2013. Chickens have likely been on the Hawaiian Islands as long as people have. When Polynesians took their outrigger canoes to the open seas, traveling thousands of miles to places like Hawaii and Easter Island, they brought the fowl on board. Today, even though Hawaiian chickens are part of island culture (showing up in ancient myths as well as on souvenir T-shirts), they’ve also proliferated in the last few decades to become a local annoyance.

When I was there a few years ago, I saw multiple restaurants with hand-painted signs asking people not to feed the chickens. I also went to a few restaurants where people had clearly ignored the signs and fowl swarmed the place, going so far as to jump up on tables to beg for food like a flock of colorful seagulls.

People started noticing a chicken boom in the years after Hurricanes Iwa and Iniki in 1982 and 1992. A popular theory is that the storms destroyed coops, sending domesticated chickens into the jungle to mingle, perhaps with populations dating back to the early Polynesians. Everyone agreed the chickens were all over the island, but no one knew what they were. Figuring out the answer was more important than just assuaging casual curiosity. Hawaii state law protected wild chickens but considered loose domestic chickens pests that should be eradicated.

To figure out the mysteries of Kauai chicken DNA, the biologists first had to catch the birds. “They can be pretty difficult to trap sometimes, and they learn,” Gering says of the experience. First, he and Wright tried catching the birds with a net gun. The net gun looks like a flashlight, but instead of a bulb in the front, there’s a carefully packed net ready to fly out and ensnare prey with the help of a little push from compressed CO2 cartridges. Online videos of people using net guns to ensnare their (willing) friends make it look like a lot of fun to use, but alas, it wasn’t much good against feral chickens. “We never caught a single bird with that thing,” Gering sighs.

Then it was the whimsically named “whoosh trap,” which uses a system of poles and bungee cords to throw a net over birds in a manner that reminds me of trying to make the bed in a hurry. It required a large area to work—hard to come by in Hawaii’s tropical forests—and every time they sprung the net it spooked the chickens, Gering recalls. They finally had some luck thanks to two relatively low-tech methods: using a gull net, which closes over birds who investigate the feed tray like a soccer goal closing over their heads, and simply building a pen then pulling the door shut behind the chickens when they wandered in.

The birds are (rightfully) suspicious of new things in their environment. Gering says they had to leave the gull nets in place for a few days and cover the edges with leaves or grass before the chickens would step into them. “Otherwise, they’ll walk to it and lean over it with their heads but won’t step into it,” he says. “It’s really cute.”

From there the work was relatively easy. They removed the birds from the trap and wrapped them in a towel “like a little burrito,” Gering says. They’d take a blood sample, feather sample, and some other measurements, then let the birds go. Each bird took about five minutes to process. Not that it was a pleasant job. At times, they couldn’t wear bug spray or sunscreen or they’d risk getting the chemicals on the birds and potentially contaminating data. They did a lot of their work in the early morning, but this is a tropical island near the equator—the sun is harsh and the bugs are everywhere. “Then there are the worms,” Gering says with a tinge of lingering horror in his voice. “Almost every single bird has worms in their eyes. It’s really disturbing.” The life of a field biologist is fascinating but rarely glamorous.

When they got the DNA results back, the conclusions were surprising. Gering and Wright found that the birds weren’t junglefowl or domestic: they were both. They were something new.

“In general, if you ask biologists or laypeople which genes will win, they’d say the wild genes because domestic chickens will stare at the sky and drown when it rains,” Gering laughs. But Kauai’s birds had selective sweeps—beneficial genetic mutations that become common among a population—from domestic breeds that are associated with increased growth and reproduction. Interestingly, the roosters also tended to have much larger combs and wattles than those seen in wild chicken species. The hens just couldn’t resist a man with a fleshy red face. These are all traits that human breeding helped select into existence. While it’s possible that traits for higher reproduction and growth might have developed naturally given enough time and genetic mutation, human care and selection sure made it easier. In the feral population, chickens had junglefowl genes that were linked to brooding chicks, a trait that has mostly been bred out of domestics. Farmers don’t like it when their chickens go broody, but, in the wild, the only way to keep the population going is to have good mother hens. There’s also evidence that Kauai’s chickens lay eggs seasonally like junglefowl.

The birds can’t undo domestication even when they live in the wild, but what they’ve become is more impressive than the label “feral” might lead us to believe. These aren’t just chickens who are surviving: Kauai’s wild chickens are thriving. They’ve taken the best of human selection and combined it with the traits that are important to their survival in the wild almost like avian cyborgs.

“I’ve never had anybody overestimate what those feral animals can achieve,” Gering says. People talk about feral animals like it’s a fixed state, he tells me. But he prefers to think about feralization as a verb, a process. A domestic animal is released into the wild. He survives long enough to make himself at home. He goes feral. But as feral mothers have offspring and meet with differently adapted members of the species and new environments, the animals keep changing.

I can’t help but wonder whether if we left them alone long enough, maybe these chickens could surpass their “feral” label to become a subspecies—similar enough to interbreed with domestic and wild chickens but perfectly and specially adapted to their island environment.

Reprinted with permission from Under the Henfluence by Tove Danovich, Agate, March 2023.