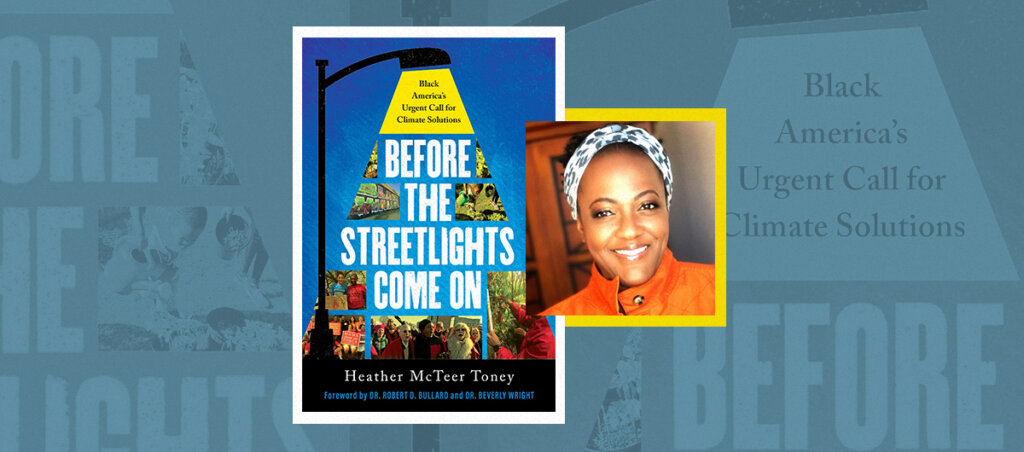

In this exclusive excerpt from 'Before the Streetlights Come On,' the Environmental Defense Fund's Heather McTeer Toney reveals the hazards of excluding Black and brown communities from the conversation around global warming.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

If you’ve ever worn, or know someone who’s worn, one of those exercise sweatsuits or waist trainers, then you know exactly how global warming works. People use these devices to aid in weight loss and burn fat. The shaper itself is made of a heat-trapping fabric, often neoprene or polymer and you just put it on and exercise. The suit increases your body heat which then activates your body to sweat. As you sweat, the moisture you expel is trapped inside the suit, creating more heat and in turn, more moisture. When you take it off, the inside is typically drenched in sweat and you may have lost an inch or a pound due to the loss of water weight, not necessarily fat. Some may argue whether or not this practice is healthy. But hey, if you need to get into a dress for a special event, what’s the harm right?

When it comes to global warming and climate change, the Earth is wearing a waist trainer in the form of greenhouse gases. There are main gases including water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, ozone, nitrous oxide and chlorofluorocarbons. The one to watch is methane gas. Once put into the air, methane traps heat in the Earth’s atmosphere making the planet hotter. Just like the waist trainer, methane creates an immediate reaction that causes the planet to heat up and sweat profusely. We experience the Earth’s sweat as moisture in the form of melting glaciers, sea level rise, and extreme weather. Hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and heat waves are results of the Earth sweating too much.

2020 marked one of the strongest and longest Atlantic hurricane season on record. Storm after storm battered the Gulf Coast and states including Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Before cities and towns had a chance to catch their breath from one storm, the next one was forecast. 2020 was so dynamic that there was a zombie storm. That’s right, a storm that blew across the Gulf, traveled across the Southeast United States, went up out and back into the Atlantic Ocean, DIED, only to be reborn in the warmer than usual waters of the Atlantic, turned around and came back through the same path again. That’s how gangster the storms were in 2020. While the toughness and fortitude of the people in the Gulf Coast region were not to be doubted, no one should be expected to fight off actual storms like Brad Pitt fought off zombies in the movie World War Z. More of these extreme storms will occur as the climate crisis continues to strengthen. If we don’t do something now, we will all soon be drowning in the Earth’s sweat. Earth has to take off the waist trainer or we’re all going to pass out.

Climate-justice principles and common sense say that the first place to reduce methane and invest in climate-resilient infrastructure is in the communities hit hardest by both pollution and extreme weather. Some climate scientists agree that not only is methane pollution a major factor in global warming and climate change, but if we’re going to be effective in fighting climate change then we must deal with methane first.

Compared to carbon dioxide, methane doesn’t last long in the atmosphere but it packs a punch while it’s there. It heats the planet 80 times more than carbon dioxide. It’s like a quick and powerful high, cocaine vs. weed, and in the words of Rick James, “Cocaine is a helluva drug.” Reducing methane pollution in the atmosphere can slow global warming by almost 40 percent. Everyone seeking to address Earth’s care must, at a minimum, acknowledge the disproportionate impact of global warming to vulnerable, underserved populations and understand that methane is a huge contributing factor.

Methane pollution can be attributed to many sources, but the biggest are agriculture, natural gas, oil operations, and landfills. Agriculture accounts for the most—30 percent of all methane pollution can be attributed to some form of agricultural practice. Oil refineries and other energy-producing facilities account for another 25 percent and are often the most toxic pollution sites. Refineries are peppered around the country and are primarily located in low-income communities and communities of color. These sites not only contribute to poor air quality for the residents that live next door, they pour millions of tons of methane gas into the atmosphere, further weakening our ability to ward off climate change.

The combination of heat-trapping gases like methane and extreme weather is deadly. In 2020, fenceline communities were already quarantined with children home from school and parents that worked as frontline workers and critical-needs staff. Once hurricane season hit, the weather added to the worries of people who were sick from living next door to petrochemical and oil refineries. At the beginning of the pandemic, local residents had to figure out a way to not only sustain themselves economically but to make sure that the community remained aware and prepared for the next storm. From the arrival of Tropical Storm Cristobal on June 7, 2020, through the landfall of Hurricane Sally on the 14th, communities along the Gulf of Mexico petrochemical and industrial corridor experienced five named storms in one summer. Throughout the summer of 2020, neighborhoods were learning how to quarantine at home, manage the essential nature of their work environment while trying their best to breathe under a cloud of pollution and the threat of rising racism targeted at minorities.

When the first storm hit, the air was already black from toxic pollution. Typically, petrochemical facilities have to do what’s called a burn-off. A burn-off means that the facility is burning off toxic emissions so that if the storm cuts power to the facility or the operations of the facility are damaged, there is not an explosion that would take out the entire area. These burn-offs are often toxic to breathe. A burn-off also includes a shelter-in-place mandate which requires people to stay inside their homes. Imagine riding out a storm—without electricity, air conditioning or water—under a shelter-in-place mandate due to poison in the air— amid a pandemic—while trying to go to school. It is hard to imagine it once, let alone five times. Nevertheless, under a cloud of pollution, an impending storm and quarantine, Black folks did what we’ve always done—figured out how to thrive and survive. Think of how many lives, how much time, money and property could be saved if we reduced pollution to begin with?

It’s not easy. Weaning humanity off of the fossil fuel energy sources that are causing climate change and methane pollution isn’t as simple as shutting down polluting facilities or halting the consumption of meat. Families rely on jobs provided by the oil and gas sector. Hamburgers are a staple in the American diet. Many of our day-to-day activities rely on factors that produce heat-trapping gasses. Whether it is putting gas in the car, turning the lights on in your home or throwing steaks on the grill, pollution-causing activities are more common and frequent than we think.

To make matters worse, the oil and gas industry—also known as the fossil fuel folks—have devised tactics to purposefully dupe Black and brown communities into thinking that fossil fuel work is good and necessary for low-income and minority communities. I don’t know too many folks willing to trade their low-cost heat bill and the family BBQ for the sake of the planet. But the message becomes worse when the oil and gas industry is pumping billions of dollars into pro-natural gas, campaign ads, messages supporting anti-climate political groups and, believe it or not, local environmental justice and faith-based groups. In minority communities, the repeated message that solar and wind power will raise your electricity bill translates into rich white people wanting poor folks to pay for saving the planet. This is the message that fossil fuel lobbyists pushed in 2021. The American Petroleum Institute (API) spent almost $11,000 a day on Facebook ads alone, targeted at minority populations. The message was simple—vote no against higher energy costs and vote no on an energy tax for the poor. It’s almost impossible to convince the average, middle-income white person, let alone Black, brown or any poor person, that rich climate advocates aren’t trying to steal their jobs and increase the light bill.

They tried it with the NAACP. In 2014, the Florida NAACP chapter was convinced to slow solar panels on housing because of the energy industry lobby. Then in 2017, a study from the NAACP found that over one million African Americans lived within a mile of an oil and gas operation and were 75 percent more likely to live in fenceline communities. As a result, African Americans were exposed to a higher rate of pollution-related health ailments than the average American. American Petroleum Institute (API) said nope, African Americans have more health ailments simply because they’re Black. API money poured into NAACP local chapters and in 2018, the California NAACP chapter opposed government programming that supported renewable energy. The fossil fuel energy lobby machine was pouring millions of dollars into targeting minority-focused organizations around the country and it was working. Every single tactic was designed to create a question of job security or to create doubt in the facts. The NAACP fought back by establishing its own environmental justice division and educating members about environmental advocacy and rights. Led by award-winning environment and climate justice advocate Jacqueline Patterson, the NAACP’s Fossil Fueled Foolery 2.0 report listed the top ten ways the fossil fuel industry works to protect their bottom line versus doing what’s good for you and me. It serves as an invaluable reminder that every message to our community should be not only vetted, but shaped and shared through trusted channels that we’ve cultivated over generations. As my pastor would say, “In God we trust, but all others we verify.”

Imagine that person who’s worn the waist trainer for so long and has been told they look good because of it. “I mean, it’s hard to breathe but I’m getting used to it. It feels ok. It must be all right … right?” The longer it’s working, the harder it becomes to take off. The first-world reliance on coal, oil and gas happens under the false impression that there isn’t that much harm being done. But that does not mean that harm isn’t happening.

Black people—as do all communities of color—have a lot to contribute to the climate conversation. Having our voices in the room will aid in the development of policy, equitable solutions, adaptation and resiliency that both empower and embolden people to do it for themselves and the world. As card-carrying members of the Earth’s ecological club, equitable climate action and climate justice are the dues we all pay to stay here. But failing to address lopsided and inconsistent impacts means that some people have been carrying the weight of others.

It all starts with remembering our history of resiliency—remembering how we adapted to the barriers of nature in the evolution of our freedom. We don’t need waist trainers and sweatsuits to be healthy, whole, and free. Some of us were built like apples and pears and that is okay. The planet is too. The lessons of adaptation and reliance on natural elements and boundaries are born from the stories we share of survival. We must show up for the conversations and see ourselves as part of the climate story.

Reprinted with permission from Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions by Heather McTeer Toney copyright © 2023 Broadleaf Books.