Getting older often feels like a rude awakening. But for this writer, who was about to surpass her late mother’s age, the number 39 took on a whole other meaning.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

This is the last summer of my 30s. My youth is not over, not just yet, but it is rapidly wrapping up.

The two or three gray hairs near each of my temples, which had been the only ones of their kind until last autumn, have recently, and rapidly, sprouted company. The “Dark and Lovely” hair color I’ve used for brightness turn these new strands a dishwater shade. For a few days, they might appear as highlights, but they soon petulantly expel their magic and become dreary.

Dreary is not what I’m going for as I head into my 40s. I am looking for exuberance. I’m going for unapologetic self-acceptance and celebration.

A chiropractor who treats some current and retired sports stars is always kind enough to fit me in when my hips and shoulders feel stiff. I tell myself it’s because he finds me refreshing. In many respects, not including the gray hairs, I’m youthful for my age. Many people my age, I’ve discovered, have grandchildren. Perhaps this is not always the case in New York City or LA, but it is true in the middle of the country, or in the middle of states I don’t often visit.

I do not have children or want them. For some, this might place me in the category of fallen women. I consider myself simply decisive. I also consider myself child-free, not childless. I am a Black woman, and because I am fairly good with kids and fairly educated, my lack of desire to be a mother often confounds people; it even angers a few. It’s not that I didn’t listen for the possible call of maternity. When I married at 28, lots of people insisted I would suddenly want children. When I turned 30 and did not, some folks uttered two of the most bizarre statements in the English language: “Just have one and see,” and “It’s different when they’re your own.”

I am surrounded by children in my role as a teacher, mostly delightfully moody preteens on the cusp of adolescence, but they do not come home with me.

After a long day with adolescents who would rather trade finger skateboards and bid on rare, expensive sneakers than craft essays on Jason Reynolds, Adrienne Rich, Ibram X. Kendi, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Heather Cox Richardson, I do not want to wrangle my own preadolescent folks to T-ball or gymnastics. What I want is to have a glass of good Malbec and enjoy it somewhere sparsely decorated, quiet, and chic. The bands I go see—Dave Matthews, the Indigo Girls, and the Roots—have audiences who appear to be galloping toward middle age or who are well beyond it. When I was at Jones Beach on Long Island jamming to “Two Step” with my friend Toren, I looked at the Gen-Xers and very old millennials clutching giant cans of Liquid Death and Twisted Tea, and clucked to myself, “Is that what I look like?”

My students listen to Jack Harlow and Billie Eilish, and the only two presidents they’ve known are Obama and Trump.

I never take my age for granted.

My mother was this age, 39, when she passed away from a terrible, metastatic breast cancer. I was a senior in high school looking forward to literature classes and D-1 track meets at the state school 45 minutes away. One weekend in May was her funeral, the next was my senior prom, and the next was graduation.

One of my great sadnesses is that very few people checked in on me after the trauma of losing my mother. My high-school friends considered me a drag; some even told me so. My mother’s thicket of colleagues and friends seemed to disappear almost overnight. My father was a 44-year-old widower with three sad children who didn’t think to suggest therapy or grief groups.

Then George W. Bush lost the presidential election and still got to be president, and Al Gore went off to make documentaries. The economy went to shit. I took teacher certification classes and toiled as a case manager for foster kids for $14 an hour.

That was my kickoff to mother loss, adulthood, war, and recession. So when I get to blow out the “4” and “0” candles on my cake later this year, I will take comfort in the ways I have mothered myself, and joyfully done my part for the next generation.

Someday I will get old. Not just yet.

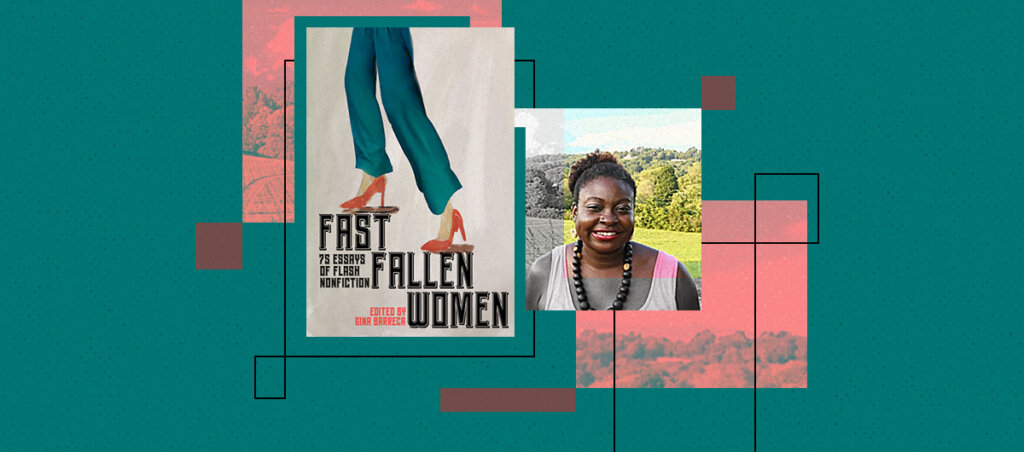

“Feeling 39” by Ebony S. Murphy, published in the essay collection Fast Fallen Women, edited by Gina Barreca, in September 2023, is printed with permission by Woodhall Press.