Sofia Coppola is the filmmaker laureate of adolescent female loneliness. But “Priscilla” offers only a glimpse of the woman who ultimately emerged from the constraints of a hauntingly abusive marriage to a bedazzled monster.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Roughly midway into Priscilla—Sofia Coppola’s chamber piece of a biopic about Priscilla Presley—there is a moment that defines the film’s greatest strengths and its major failing. During a sun-soaked shindig at Graceland befitting any of Elvis Presley’s beach party movies, Priscilla (Cailee Spaeny) lounges on a beach chair, camera pointed toward Elvis (Jacob Elordi) in the pool. Up until this point, Priscilla has existed to be beheld: an object of dominion and desire for a powerful man, a locus of envy for his fans, and a pretty piece of background furniture to all his hangers-on and enablers. Now, she’s the one holding the lens, the one with the power to perceive. That is, until Elvis—hailed by teen fans as “the King”—comes slinking out of the water, less a hunka-hunka-burning-love than a chlorinated sea snake writhing on top of her. In their teasing, uneven struggle, the camera is knocked out of her hands, tilting up toward a slanted blue sky as she squeals protestations that are shot through with delight.

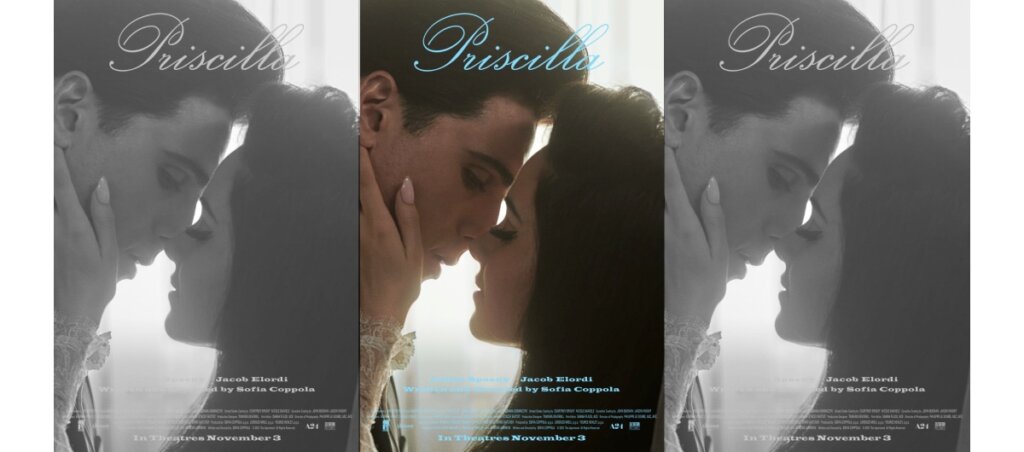

As an offering from Coppola, our cinematic poet laureate of adolescent loneliness, Priscilla is something of a bloodless horror film following our heroine ever deeper into a haunted house of a relationship. Only the monster in the attic is the handsomest man in the world. The courtship is a series of explosions—from large-scale detonations, as when Elvis throws a chair at Priscilla’s head for her crime of responding honestly about whether she liked a new song, to the smaller eruptions of his casual demands about which colors he wants his wife to wear. The couple’s ten-year age gap—he was 24 and she was only 14 when he arranged to meet her—is referenced repeatedly, and the visual discord between the doll-like petiteness of Spaeny and all six-foot-infinity of Elordi only reinforces the skewed power dynamics of an adult pursuing a minor.

If Priscilla herself is often regarded as an Aqua-Netted accessory in stories about the King, the movie bearing her name attempts to finally center her. The very first shot doesn’t evoke the Great Man at all: It focuses on Priscilla’s bare feet, toenails painted in a fresh, candy-glossed pink, stepping onto a soft pink carpet. It’s an exquisitely intimate, vulnerable image given greater potency by the baroque darkness of her room. Yet, for all of Coppola’s efforts to reclaim Priscilla’s girlhood inside the golden cage of wifedom, the movie falls short of portraying her as the woman who will eventually gain the independence to drive out of the barred gates of Graceland. Thematically, the camera gets knocked out of her hands. The screen fills with empty blue sky.

When Coppola first announced her intention to take on Presley’s best-selling memoir, Elvis and Me, online pearl clutchers expressed concern that the very act of depicting a toxic relationship between a grown man and a teenager was akin to condoning it. Priscilla has been released into a uniquely infuriating moment in pop culture discourse, where literalism rules the day, and a very vocal swath of younger viewers seem particularly repulsed by the idea that filmmakers might dare portray troubling aspects of the human experience—especially around sex. Coppola’s film is more remarkable, then, for walking a very fine tightrope: Showing extreme awareness that the central relationship was founded on grooming and predation, while still acknowledging Priscilla’s very real, very painful need to be wanted and loved—even by a man who hurt her.

Spaeny holds subtle command that conveys youthful innocence and inquisitiveness, and all the shades of heartache, from pinprick disappointment to torrents of rage. Clad in a simple schoolgirl’s choker of a gold heart on a thin black cord, she gazes at the heartthrob from her album covers as he sits beside her, pouring his heart out about grief and homesickness (tellingly, he never asks her much about herself), with an expression that shifts between incredulity, awe, desire, hesitation, and tenderness. The audience knows that a man who has his colleague procure her for parties will do her no good, even if he swears to remain chaste and says the right things to her concerned father. Yet the movie still does the difficult work of exploring Priscilla’s feelings with nuance and dignity.

Coppola often elevates her set design to become a core part of the narrative—from the sleek yet aloof Japanese cityscapes of Lost in Translation to the oppressive and seductive glitz of Marie Antoniette’s Versailles, or even the hothouse malaise evoked by the decaying plantation house of The Beguiled—and young Priscilla’s family home and life at school is a wan wash of muted tones. Her mother alludes to a difficult transition to life on the military base. She seems uninterested in her studies—and who would be, when the most famous man in the world has fixed his eye on you? As Priscilla cycles through identities, becoming a lovestruck teenager; a girlfriend who is alternately doted upon or picked apart when she’s not outright ignored; and a wife who finally breaks from the untenable loneliness of being an accessory, her moods are reflected through her environment. The colors of Graceland, initially bold and sumptuously rich against the blandness of early girlhood soon become smothering, with Elvis’s bedroom dark as a tomb.

While Lolita-core has remained an uncomfortably dominant strain in pop culture eros—from the fetishization of Catholic schoolgirls as sirens and assassins, the forced coy-sexpot personas of early aughts superstars like Britney Spears, to Lana Del Rey’s rise in the contemporary music charts, and the blood-and-glitter pageantry of titillation among the teens on Euphoria—in the aftershocks of #MeToo, there’s been a broader, if still woefully incomplete reckoning with how teenage exploitation is portrayed on-screen. Priscilla deepens this conversation by putting viewers behind the eyes of a girl enthralled with her abuser.

The aesthetic of Priscilla as a cat-eyed, beehived bride in a delicate white dress next to a groom with a cigarette perched on his lips, or a tiny girl in a chicly rumpled cocktail dress stumbling sleepily out of a Vegas lounge with a beautiful brute’s arm slung over her shoulder has its own dark glamor that is not to be dismissed. That bruising, moody sensuality, destructive as it is, is broadly appealing enough to make an artist like Del Rey—author of wry, lonely girl paeans to a classic Americana where manchildren are men and women are made to scratch the same painful itch, with lyrics like, “you’re fun and you’re wild. But you don’t know the half of the shit that you put me through”—a pop culture icon. Del Rey’s music is the soundtrack to many a TikTok fan video of Elvis and Priscilla, and now Elordi and Spaeny as Elvis and Priscilla, particularly “Young and Beautiful,” wherein our heroine beseeches Heaven to take her man—who’s not good enough to get in of his own volition but makes her “wanna party” and “shine like diamonds.”

Whether these fans are aware of the tragic irony in being slowly annihilated by the person who sparks your desire or taken in by the drama of doomed love (or love’s taboo facsimile), they’re responding to a force that the real-life Presley herself felt, to her own detriment: “I don’t think I’ll ever find anyone I’ll love as much as I loved Elvis,” she said. “It’s pointless trying to compare him to anyone. Yes, some men I’ve been with have mattered to me, but Elvis was my first love, he’ll be my last.” While her words may carry a superficial sheen of romance, they also take a stake to the insidious, vampiric heart of grooming—Elvis found her as a child, seduced her and berated her into a perfect, malleable doll who could never imagine a life on earth, or in Heaven, without her man. Who could only shine, diamond-bright, under his eye.

However, despite the film’s delicate yet potent excavation of Priscilla within the relationship, its work of allowing her to be the lens through which it is viewed, Priscilla is surprisingly slight in portraying its heroine outside of her “first love.” While maintaining a cosseted vantage point is effective for the first half of the film—keeping viewers as breathlessly immersed in the relationship as Priscilla is—the build toward her revelation that “I lived somebody else’s life. It was never about me, it was really about him on every level” feels shallow and rushed.

Priscilla begins to fray at its edges around the time Elvis mounts his comeback residency in Vegas, becoming increasingly dependent on pills and uninterested in even pretending to be a family man. The movie rushes toward its bitterly triumphant ending—with Priscilla leaving Graceland for the last time, Dolly Parton singing “I Will Always Love You” in the background (a song Parton wrote and famously refused to allow Elvis to cover because his manager insisted on taking half the publishing rights)—without fully articulating what finally, irrevocably makes Priscilla break out of her gilded cocoon.

While the evolution is signified in her eschewing the black dye for her natural brunette, opting for the patterned clothes he mocked as unflattering, and choosing a home for herself with cheerful, sunny spaces, there’s no sense of what sparked these shifts. In real life, Presley attributes an affair with her karate instructor—after years of Elvis withholding sex to control and punish—as a turning point. Yet, in the film, this moment of transformation is given too light a touch. Literally. It’s her lingering hold on his arm at a dinner party. So slight that anyone unaware of the true history might miss it.

If Coppola can turn the discord between the power of Priscilla’s first longings and the unworthy object of them into a heartbreakingly delicate note, why can’t she show Priscilla experiencing desire anew, as an adult woman? After her divorce, Priscilla would become a successful actress and entrepreneur—going on to run her own boutique, Bis & Beau, and eventually saving Graceland by turning it into a celebrated tourist attraction—but the movie applies none of its stunning interiority to these shifts. Even Priscilla’s life as a young mother is mostly glossed over.

As a stylized rhapsody on femininity and loneliness, Priscilla feels like a cinematic granddaughter to Coppola’s earlier work about another pop princess, Marie Antoinette. There are even parallel scenes of both girls stifling tears after enduring public humiliation, shuffling stoically out of a room until they can finally break down, in private, behind a closed door. Yet Marie Antoinette provides a holistic view into its titular character, showcasing her suffering, and eventual success, in the fishbowl of life at court; her need to want and be wanted as a lover; her desire to perform on-stage; her love of finery and the country life; her youthful recklessness and love of her children. From a few threads, the movie weaves an ornate tapestry of a whole woman. There’s a version of Priscilla with a similar depth and range, one that breaks hearts with all that its heroine endures and revels in the person she becomes.