Zoomers and Alphas have grown up during a horrific era of lockdown drills, school shootings, and polarizing political violence. Is there any hope for building a safer future?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Like many Americans, I first saw news of the assassination attempt on Donald Trump in a “BREAKING” alert on my phone. I showed the story to my husband at a hot-pot restaurant dinner table where we sat with our daughter. We exchanged a quiet glance of adult panic. What would this mean for the country? Would violence breed violence? There were TVs in the restaurant. We had to tell our daughter before someone flipped ESPN’s coverage of a UFC cage match (and barehanded blows she’d never before witnessed) to the news’s wall-to-wall coverage of gunfire.

As she absorbed the news, I didn’t see the fear and panic I felt as my eyes scanned for more reports in the days that followed. It was awful, sad, she said in a steady tone. She did have questions though. Why was the shooter killed and not arrested? If killing is wrong, it’s wrong in all cases—isn’t it?

She could look at the incident in the abstract and begin asking moral questions when all I could see was blood and an uncertain future.

In the nearly two weeks since the assassination attempt, I have felt a distressed hum behind my eyes as CNN’s B-roll looped former president Donald Trump clutching his ear and dropping to the ground. As he rose—blood splattered across his face and fist raised, shouting, “Fight, fight!”—my adult brain struggled to process the reality that I was also watching a scene where another man, 50-year-old Corey Comperatore was murdered. Our country again had been transformed by the horror of violence. Days later, as cable news talking heads contemplated how the Secret Service had failed, the footage restarted in a corner box on the screen. A hand to the head, popping, people dropping to the ground. My mind’s eye filled in the next few seconds with what I had seen in clips online: rally-goers who saw Trump was alive turning in celebration to raise middle fingers at the press, yelling “Fuck you!” and “USA! USA!”

As I was puttering in the kitchen last week, my tween daughter mentioned how she and her friends had watched clips on her friend’s phone, a TikTok habit they’ve developed as they lounge on that friend’s trampoline in the summer sun. “Not the part with the blood,” she said, expecting a lecture. She was managing me. Then she asked what we were having for dinner.

***

Some Gen-X parents may have fuzzy childhood memories of the assassination attempt against Ronald Reagan and important lessons from their own parents who might have opposed his policies but didn’t want to see the man shot. For the most part though, Gen X and Millennial parents grew up in a period that was relatively free of political violence. Some were out of school before the massacre at Columbine, and most were through their developmental years before lockdowns and metal detectors became the norm. The idea that children might perish in mass-killing at school is a horror unique to younger Millennials, Zoomers, and Gen Alphas.

Our kids understand people exist who plan and carry out gruesome murder on children at school or their loved ones at a concert or at the grocery store. That’s an amorphous, could-happen-anywhere, at-any-time kind of threat.

Kids know if their parents have deeply felt political views and worry that certain figures could radically change our country. If not shielded from such news, they may be aware of death threats against local school board members, shots taken at members of Congress, the foiled kidnapping plot against Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. These are worries and acts of violence that are specific. The perceived causes of political upheaval and targets of violence have a name.

In the hours and days following the assassination attempt against Trump, President Joe Biden has repeatedly said, “This isn’t us.”

It’s a claim paired with a call to dial down the boil of political tensions in this country. However, as Northwestern University professor of policy analysis and communication Erik Nesbit noted on Today, Explained, this culture of political violence is historically American. In the past ten years, political violence—which used to be split pretty symmetrically on the left and right and focused on single issues—has become more partisan and right-leaning, “at least in terms of the number of violent acts tracked by the FBI and domestic terrorism databases,” said Nesbit. It’s the culminating force of sectarianism and tribalism that dehumanizes the other side and treats political opposites as an existential threat, and in so doing, tends to elevate violence as morally justifiable.

There’s a degree to which political violence is not as wrenchingly random as other mass shootings. Political violence implies a rationale, even if we don’t know what it is. If nothing else, the immediate spin of conspiracy theories online flow from people trying to make sense out of targeted violence. The lines of good and evil are redrawn with a spray of bullets.

Adults who have opposed Trump for years want to stop him politically—not mortally. The assassination attempt has highlighted how dangerous the rhetorical warcraft of our politics has become, and also triggered empathy that needs to dwell within lasting political opposition.

Many adults are conflicted over all of this. Observing this moral complexity in adults can be baffling to kids.

I reached out to Lutheran minister Angela Denker, who writes about Christian nationalism and is the author of the forthcoming Disciples of White Jesus: The Radicalization of American Boyhood.

“My 11-year-old just told me that the YouTubers are all calling Trump a G,” she told me. She found that implication of Trump being a “gangsta” laughable—though did allow that it may also speak to Trump’s criminal convictions. Her husband suggested that right-wing PACs are really good at mobilizing influencers. Denker suspects the language is part of an appeal to Black, male voters, which Trump is leaning into heavily.

Denker, who has been warning against Trump’s authoritarian policies for years, was watching footage of the shooting and said how terrible it was. Her other son, who is 8, walked in and asked, “Why do you like Trump now?”

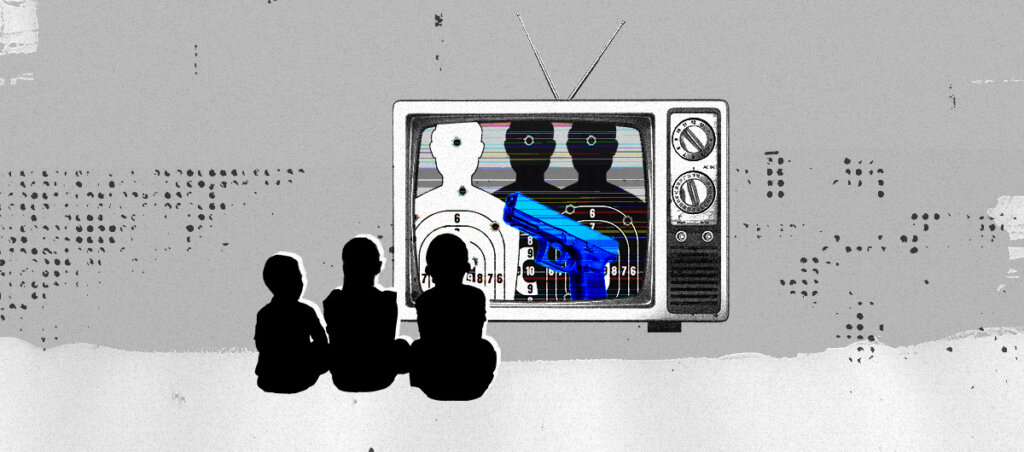

She explained to her son, “We don’t want anyone to be shot.” Denker believed her younger child is “picking up on the political tensions of the moment,” but the way the dramatic footage has been shown is similar to what a kid well-versed in video-game violence might perceive as a “bad guy” being shot.

“The shooting doesn’t seem real.” In that way, Denker said, “I think it’s a function of the ways they see violence on the screen, even if we try to limit it,” adding that “I think it’s really confusing for kids.”

***

I’ve learned other parents have also observed a gap between their own response to the shooting and that of their children. It may be the distance between adults steeped in factious political tensions and kids who have other things on their minds. It might be that younger Americans are uniquely desensitized to news of gun violence, having grown up in a time when school and neighborhood shootings are a tragically regular occurrence. Firearm-related injuries are the leading cause of death for children and teens. Perhaps our kids’ response can tell us something valuable about the state of our country, or at least its youngest citizens.

On Instagram, I discussed with Angie Liskey, a mom from Indiana, how her 12-year-old was neither fazed nor concerned by the assassination attempt. Liskey said she tries to protect her kid from what they might see in the news but did share about the shooting. “I think they are so desensitized and have been forced to dissociate from the threat of gun violence because they’ve been doing active shooter drills since kindergarten,” Liskey told me.

I thought about when my own kids were young, how they came home describing how they’d been trained to create chaos to slow down a “bad guy.” They explained their plans to hurl safety scissors or the teacher’s stapler. I knew this was a last-ditch effort for children to delay a would-be murderer in one classroom before getting to another. Those scissors could barely get through construction paper.

While acknowledging that her children do several active-shooter drills each year in school, and she and her husband ask about gun safety in friends’ homes before playdates, Kelsey Tushar, a religious trauma therapist, said she also tries to guard her young children from the news. They don’t watch the news at home. (She stays up-to-date by reading the news online.) However, she and her husband felt it was important for kids to be aware of a historic event, so they chose a 15-second clip of the shooting to show their four kids (ages 12, 11, 8, and 6). They tweaked their talks with the kids by age and understanding, having separate conversations with the two older kids and the two younger ones.

Her children, she said, do “understand the political landscape to some degree.”

Another mother living in the north of England, Emma Swai told me her youngest son had been packing up water guns to take to school for his Year 6 water fight shortly before he heard the news. (Swai said their family doesn’t view water guns as weapons). But they do have a stark impression of America’s relationship with firearms. Last year, when Swai visited Texas for a conference, “my daughter was terrified I wouldn’t come back.” Her son said he’d never want to live here because, to his mind, everyone has guns and are willing to use them. Swai explained that he thinks it’s “daft you can ban books as dangerous but not guns that kill people.”

Margaret Quinlan, co-author of You’re Doing It Wrong: Mothering, Media, and Medical Expertise, worried her 9-year-old daughter had become desensitized to gun violence when she said seeing pictures of the assassination “did not scare” her at all because “they would not show anything bad on TV.” Quinlan, also a professor of communication studies at University of North Carolina, Charlotte, said for now, she just wants her daughter to feel safe. “I realize these kids are used to the constant threat of gun violence. We’ve normalized desensitization because we won’t take the basic steps to protect our kids from guns.” Quinlan worries she too has been desensitized and is “not surprised this happened to Trump.” Such violence, she believes, will keep happening.

I’ve run across many American parents who say their teenagers in particular haven’t made a big deal out of the assassination attempt. This doesn’t mean children of any age are immune to acts of political violence. There is good reason to handle the topic sensitively. American children have had worsening mental illness rates since the pandemic, with increasing depression and anxiety. Their world has already proved itself a scary place.

“The constant media coverage of the assassination attempt on former President Trump presents a really challenging situation for many parents,” said Rychel Johnson, a mental health expert and counselor based in Kansas. “While we want to shield our children from distressing visuals and topics, the pervasiveness of this footage makes that incredibly difficult.” She strongly encouraged limiting exposure to graphic footage for younger children. “Their minds are still making sense of the world around them,” she said.

Even so, it’s likely that in our connected world, kids will see the news or learn about it from friends. And especially with teens and tweens, it’s “paramount” to speak openly and check in. “We can’t assume they are desensitized,” Johnson warned, “acts of violence targeting public figures can absolutely rattle them still.”

And shouldn’t it?

***

It just so happened that the weekend of the assassination attempt, my own teen son was miles south in Kentucky caving and camping. On the drive down the night before bloodshed in Pennsylvania, his ride passed a group of young men gathered outside shooting off rifles. When he first mentioned it, I assumed he’d traveled past a driving range.

It was not. They were just some guys hanging out alongside the road near what looked to be an old railroad switch. One had a gun propped in the bed of a pickup. They had a clay pigeon shooter and were positioned to shoot. Someone in my kid’s car identified the gun in the truck as an AR-15, and my kid’s group worried about someone down the field getting shot accidentally. I have no idea whether they accurately identified the popular semi-automatic from their moving car, but in his retelling after the assassination attempt, that moment mixed with Saturday’s shooting with the sick smack of coincidence.

“How and why do a bunch of idiots five or six years older than me get their hands on guns like that?” my son asked, shaking his head over the fact that they were using something as powerful as semi automatic weapons for clay shooting and the danger they posed to anyone downfield from the barrel of their guns. Similar questions could be raised about Trump’s would-be assassin, a 20-year old who killed one and critically injured two others in addition to striking Trump.

And that’s yet another troubling element of kids’ having to process this gruesome violence—the nearness in age of some to a young man, reportedly quiet, smart, bullied, and deadly. It’s a trope, at any age, that we all know too well.