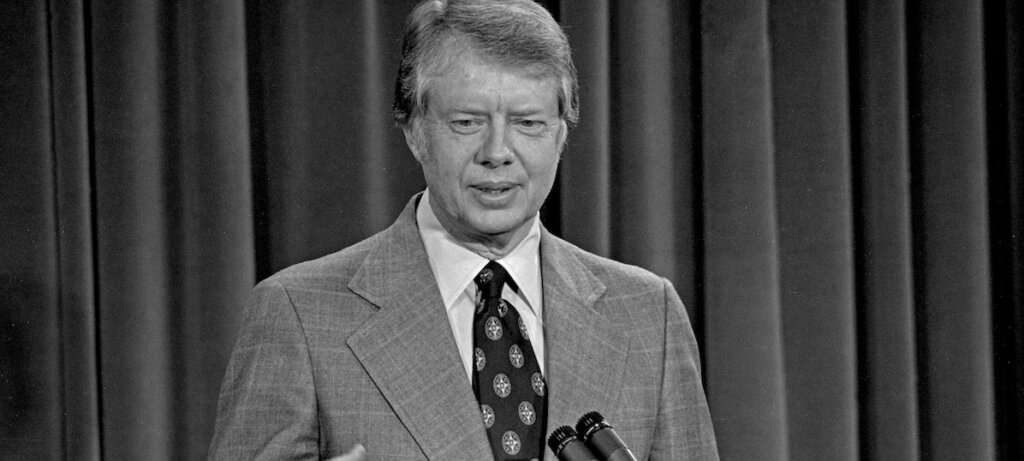

Discussing the prescient legacy of our late 39th U.S. President, who died at age 100, with biographer Kai Bird, author of “The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter.”

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

On December 29, 2024, we lost Jimmy Carter—the one-time governor of Georgia and one-term president of the United States. At 100, he outlived his beloved wife, Rosalynn Smith, to whom he’d been married since 1946, and who died a year earlier, in November 2023. Beloved for his humanitarian work, Carter is often remembered as having had a lackluster presidency followed by the luminous half-century when he used his prestige and talents to become a significant change maker in national and international efforts: In 2002, Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, particularly for his work to avert the invasion of Iraq by the United States.

Born into a farming family in Plains, Georgia, in 1924, Carter graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, and began his career in the Navy before pivoting to politics. He moved quickly up the Democratic Party in a period marked by turmoil: the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, and a nation being transformed by the Black freedom struggle, feminism, environmentalism, and numerous social movements that aimed to change what U.S. politics meant.

When I sat down to talk to biographer Kai Bird, author of The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter (Crown, 2021), the word that came up most frequently in relation to Carter’s presidency was “prescient.” Carter, Bird conveyed, understood what the next challenges would be for the nation: climate change, the Middle East, and the changing face of poverty.

DAME: As a biographer, what drew you to write about the late President Jimmy Carter?

Kai Bird: Jimmy Carter was a mystery to me. I was all of 25, and I think Carter was the first president I believed I could vote for. He was this guy from South Georgia who spoke with a funny accent; he was a liberal but kind of hard to pin down as to what kind of liberal. He had a tumultuous presidency. In 1990, after I’d finished my first biography, I was searching around for a new subject. I thought of Jimmy Carter, and talked to Victor Navasky, then the editor of The Nation. Victor said, “Well, the way to explore this is to have you go down to Atlanta and write a profile of what Jimmy Carter is doing with his ex-presidency.”

I spent two weeks [in Georgia] interviewing a bunch of the people Carter had just hired for the newly opened Carter Center. I had a short telephone interview with him; and I wrote a 5,000-word cover magazine piece about all the good things going on at the Carter Center. I concluded that I was the wrong guy to do a biography of Jimmy Carter. I did not understand the South. I did not understand Southern Baptists or their religion, and I certainly didn’t understand Southerners’ views on race. It just seemed like a foreign country to me. So, I backed off on the project, but I was still curious about Carter and sort of frustrated about how he was viewed. I came back to the project in 2015, after having written several other biographies, and by that time it was a better moment to tackle the subject. Carter’s Presidential archives had finally opened up in a substantial way, and he had published his Presidential diary, which is fabulous. And I was no longer so shy about taking on a Southern man.

DAME: Let’s talk about him as a Southern man. Jimmy Carter is one of several American presidents who were born into humble circumstances, and one of three 20th-century presidents from the former Confederacy. His family wasn’t poor, but they were rural, and operated a peanut farm in the Jim Crow South. How did all these aspects of his background shape him?

Kai Bird: It’s a very improbable story. Carter’s father was a white supremacist and believed in segregation. Jimmy himself grew up in Archery, Georgia, just three miles down the road from Plains. Plains has a population of over 600 today, but Archery was nothing. It just had a train stop, and a couple of houses. Carter grew up in a Sears and Roebuck kit house, with no running water, and an outhouse in the backyard. No electricity. As a kid, Carter spent much of the year running around barefoot, and his playmates were, almost without exception, African American. So, Carter grew up in Black culture, and his mother, Miss Lillian—who some of us may remember from her hilarious appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson—was the classic sort of eccentric Southern woman who could say anything and get away with it. She broke all the social taboos. She believed in racial equality, and she went around South Georgia saying that she admired Abraham Lincoln, which was a verboten thing to say to Southerners. She influenced Jimmy to be a Southern populist and a liberal on racial issues, and that defined his political career.

DAME: Carter was also ambitious.

Kai Bird: Yeah, he was very ambitious. He was always the brightest boy in his class, and he had the ambition to join the Navy and become an officer. He managed to get his father to find some congressman to sponsor him for the Naval Academy at Annapolis. He started in 1943, graduated in 1947, and had a seven-year career in the Navy. When his father was dying of pancreatic cancer, Carter realized he had to come back to Georgia and take over the family farm and the peanut business. That was his home, and that’s where he lived the rest of his life, except for his four years in the White House.

DAME: Carter believed that government was both a problem and the solution and kept both of those values in his head simultaneously.

Kai Bird: That was one of the issues that initially confused me about Carter. He talked about the need for small government, but he also believed in the ability of government to do good. Carter had other contradictions too. For example, his political philosophy came from his Southern Baptist heritage, and he grew up inculcated with the notion that pride was the worst sin. This is a man who also had a lot of pride. He always knew that he was the smartest guy in the room. Carter read a lot of books trying to deal with this contradiction in his persona between his ambition and his pride versus his Southern Baptist Heritage. He read Reinhold Niebuhr [an American Reformed theologian] and was impressed with Niebuhr’s view that the world is a sinful place, and politicians have the sad duty of trying to fix it. As Carter came to understand it, it was okay to be ambitious. It was okay to be ruthless in the pursuit of votes and power. But once you were in power, you needed to do the righteous thing.

Carter was a tolerant man and he understood that human rights were a principle, and he was perfectly willing to do the right thing, even at great political cost. As president, he took on the Panama Canal Treaty, which transferred the zone back to Panama; it was very unpopular, but the right thing to do. Similarly, taking on the problem of Middle East peace during the famous 13 days at Camp David, where he just twisted the arms of these two adversaries, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and the President of Egypt, Anwar Sadat, and forced them to negotiate with each other with his mediation. The Camp David Accords proved to be a brilliant piece of diplomacy, but Carter also got himself into a lot of trouble, because he argued for involving the Palestinians, and addressing Palestinian demands for autonomy or self-determination. He thought he had gotten PM Begin to agree to a freeze on settlements. This would have allowed a five-year grace period in which they could build institutions for Palestinian autonomy and trust between the two peoples.

A two-state solution was clearly the goal. Carter was prescient when it came to stopping the settlements. It was a very controversial position at the time, but he’s been proven right about this. Here we are 45 years later, and the two-state solution in Israel/Palestine is rapidly receding. But Carter warned about the dangers of going down the road toward apartheid, and he got into a lot of trouble using that word in one of his books. But people are having that conversation again now.

DAME: As Carter moved up the ladder politically, he did things he believed in without regard to their political consequences. And not surprisingly, he was also a one-term president. One of the constituencies he lost in 1980 was feminists, in part due to his personal antipathy to abortion, which led him to sign a ban on Medicaid-funded procedures in 1978. It ignited a bitter battle, not just with feminists within his own party, but within his administration. The specific issue of abortion aside: Do you think we need more one-term presidents who will stand up for what they think is right?

Kai Bird: That’s an interesting question. Yes, probably. We need people who will take on the tough issues and pay attention to the details, study the issues and figure out the right thing to do. Carter, I would argue, was without a doubt probably the most intelligent, certainly the most hard-working and most decent man to have occupied the White House. People forget this, but Carter’s one-term presidency was quite eventful and consequential. He passed a lot of good legislation that remade the country. And it was scandal-free; there was not a whiff of corruption; there were no sex scandals. There were no conflicts of interest.

There was one ugly moment early on: in the summer of 1977, Carter was forced to fire Bert Lance, an old friend from Georgia who he had appointed to be head of the Office of Management and Budget: Lance had been involved with shady business practices at his small-town bank. But none of that touched Jimmy Carter personally. He ran a clean White House and was famous for paying a lot of attention to detail, and these are things to be admired. He kept “farmer hours” in the Oval Office. He got up at 5:30 every morning, was in the office by 6:00 or 6:30, and worked 12-hour days. He read 300 pages of memos every day. We haven’t seen much of that in recent decades.

DAME: We need to remember Carter for his presidency as much as for his post-presidency, since he is generally seen as coming into his own after he left office 1980. Carter worked very hard for peace when he was president and that work continued in the decades after he left office, even as his vision for the world kind of crumbled. What kind of international work was Carter doing behind the scenes? Did other presidents welcome his presence in international affairs?

Kai Bird:Carter was very active, and the presidents who followed him were always nervous about what he was doing. Bill Clinton, in particular, was notably annoyed when Carter flew off to North Korea to negotiate with Korean dictator Kim Il Sung about his nation’s nuclear program. Carter made a breakthrough and got an agreement that lasted for a few years: It delayed North Korea’s acquisition of those weapons. President Clinton was annoyed to no end because, for one thing, Carter announced the deal on CNN, not at the White House. He didn’t give Clinton a chance to get in on the act, and politicians don’t appreciate people who do that. You know, there are all these reunions of ex-presidents; they occasionally gather in the Oval Office or somewhere, and there’s always a photograph of them: Carter is generally off to the edge. He’s always separated by about two feet from anyone else. I interpret that as nervousness on the part of people like Clinton, Ronald Reagan, or George W. Bush about this very intimidating, righteous, politician who they probably felt judged them and made them look not so good.

DAME: One of the projects most closely identified with Carter’s post-presidency is his work with Habitat for Humanity, an organization that helps poor people own their own homes through sweat equity. The U.S. currently is suffering one of our most significant housing crises since World War II. Does this show the limits of Carter’s vision for social justice through philanthropy and community action? It seems we really need the government to enforce housing justice.

Kai Bird: Habitat is a great organization, but as you say, it’s a drop in the bucket in terms of what needs to be done. Carter did give it visibility. For 40 years, he would donate one week of his time every year, helping to build a house—sometimes in the Bronx, or sometimes abroad. It was a good thing, but it was symbolic. Carter was a small-town fiscal conservative in his instincts. He knew that the government could and should do good, but he was very skeptical of government waste and big spending programs. He was willing, if you could prove to him that it worked: For example, the SNAP program got food to poor children and working-class people struggling to feed themselves. It largely benefitted rural Southern Black Americans in places like where Carter grew up, and he expanded it, making millions more people eligible by taking away the requirement that they first had to pay a $75 entry fee, a huge barrier to poor people. Carter understood the value of helping and of having the government do good for the poor. But he was very skeptical about other federal programs. Early in his first term, he vetoed a big $5 or $6 billion program to build a bunch of small dams on rivers and streams in every congressional district across the country. It was very popular with congressmen, and Carter looked at it and said, It’s a waste of money, not necessary, and it damages the environment. I’m just going to veto it. This enraged Tip O’Neill, the Democratic Speaker of the House.

DAME: Not supporting politics as usual was another reason he was a one-term president, right?

Kai Bird: Well, right. O’Neill couldn’t understand why Carter wasn’t filling the pork barrel. It’s good for politics! Carter didn’t understand this at all, so he was constantly a mystery to his own political allies.

DAME: Carter and his staff were often portrayed as hicks who didn’t really understand Washington, didn’t have any friends there, and weren’t connected. But maybe they just didn’t like how Washington worked.

Kai Bird: Oh, it was oil and water. Carter hated the Georgetown cocktail party circuit. In one of my interviews, I asked him: “Sir, why did you turn down so many dinner invitations from Katherine Graham?” She was the publisher of the Washington Post and would routinely invite Carter to come over to her mansion in Georgetown and have a cocktail and a lavish dinner. He said, “Well, in retrospect, maybe that was a mistake.” But he hated that scene; he would rather socialize with a few friends with a can of beer and a slice of pizza, or maybe with Hamilton Jordan and Jody Powell, his two closest aides. He actively avoided the Georgetown set and Washington society. So, they couldn’t figure him out. They couldn’t even figure out his Southern accent. Sally Quinn, Washington Post’s “Style” section reporter, wrote these nasty profiles of Hamilton Jordan and Jimmy Carter, making fun of them, essentially for their Southernness. Pat Oliphant, the political cartoonist, portrayed the White House with tire swings on the trees, an outhouse, and Jimmy Carter standing on the front lawn in overalls and with a piece of hay sticking out of his teeth.

DAME: The Reagans played into that when they came into office in 1980 and announced: There’s going to be style in the White House again. Everything is back to normal.

Kai Bird: Yes, and take down those solar panels that Jimmy Carter put on the roof.

DAME: What aspects of Carter’s legacy are relevant to us now?

Kai Bird: Jimmy Carter was prescient about all sorts of issues, particularly late in his presidency, and particularly on the environment. For example, he issued the first federal government report on global warming that predicted the consequences of carbon buildup in the atmosphere and the problems we’re facing with climate change today. Carter changed America in many ways, but we’re also still living with some of the issues that he grappled with and couldn’t solve, like Iran. The Iranian revolution, and the hostage-taking, wounded his presidency severely, and here we are, 45 years later, still in a stand-off with a theocratic, reactionary state and trying to figure out how to rein in its ambitions. We’re still grappling with the Arab, Israeli, and Palestinian conflict that Carter tried to resolve. And no president has been able to make more progress than he did.

Then, there was the so-called “malaise” speech in 1979. Although Carter didn’t once mention the word malaise, it was a downer of a speech, one that only a Southern Baptist could give. He talked about the fact that the American people had to realize that they could not seek happiness only in material goods; that Americans had to stop thinking only of ourselves as individuals. That 1979 speech was classic Carter, speaking from the heart and talking in sort of populist terms about values and community and the environment and human rights. But it was a speech that most Americans did not want to hear. They wanted to hear Ronald Reagan get up and talk about how America is still an exceptional nation, a shining city on a hill. President Carter was talking about the culture of narcissism. Christopher Lasch’s book, of the same name, was a bestseller at the time; Carter had read it.

Well, he was absolutely right! Look where we are now.

Note: Interview edited and condensed for publication.