This isn’t the first time in U.S. history that the oligarchs wielded tremendous influence over the government. But now, with far more money and control over our information, they’re poised to seize power. Here’s a primer.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

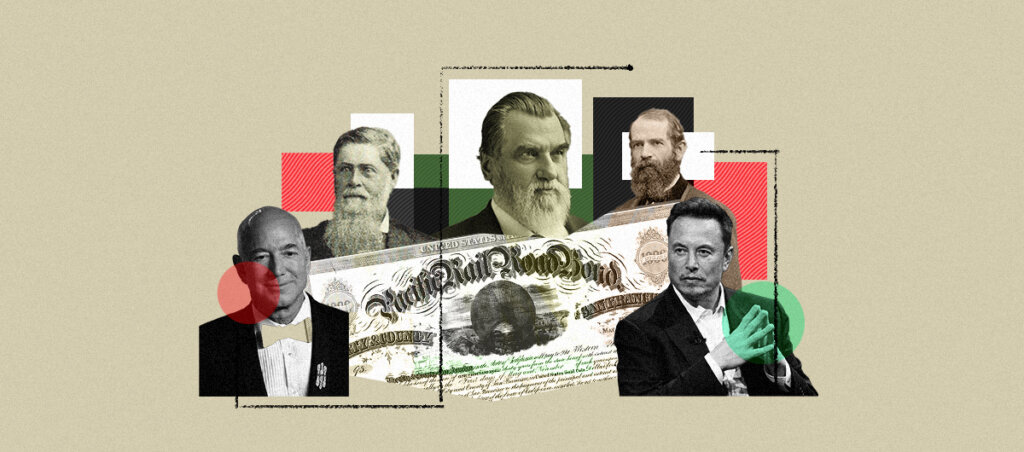

There is a huge chasm between the wealthiest Americans and the rest of us. In 2024, it came out that Jeff Bezos makes roughly $7.9 million an hour—more than three times as much as a typical college grad earns in their whole lifetime. The 801 billionaires in this country hold a combined $6.2 trillion of wealth, and their influence is felt everywhere in American life: They own tech companies, media companies, car companies, and the like. The last time there was this level of income inequality in the United States was during the Gilded Age in the 19th century. Now, in the 21st century, the billionaire class is shoving us into another.

The term “Gilded Age” was coined by Mark Twain in his novel of the same name, and refers to the period in U.S. history between 1865 and the late 1890s of unprecedented industrial growth, fueled by railroad construction and improvements in steel manufacturing. Cities grew at a breakneck pace: In 1800, around 5% of Americans lived in cities. By 1900, that number exploded to 40%. It was also a period of incredible wealth inequality and poverty—4,000 families in the United States had as much money as the other 11.6 million combined. For the majority of Americans, life was hardscrabble. People worked around 60 hours a week, and, in the cities, they lived on top of one another, jammed into tenement buildings and squalid apartments.

Those who became rich during the Gilded Age became known as “robber barons.” The term was first used to describe a financier, Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1859, and evoked both the wealth and the power these men enjoyed. Indeed, they wielded tremendous influence, and while their fortunes today might seem small compared with Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg, they had an outsize presence in American life. The businesses they built owned land as big as whole states, hired small armies of private detectives like the Pinkertons, bought newspapers, and ran massive industries.

Today, the Trump administration is powered by billionaires. Many conservatives have even been trying to create a new Gilded Age for more than a decade, from the Cato Institute questioning whether extreme income inequality or predatory pricing is actually a bad thing, to glossy descriptions of how life wasn’t so bad for steelworkers from Prager U, to the National Review describing how the robber barons have really gotten a bad rap.

Now their wish appears to be coming true: Our modern robber barons like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Donald Trump, Linda McMahon, and others all are going to be in position to set policy in Washington. What can we expect?

Rent-seeking

The building of the transcontinental railroad is cited as one of the great achievements of the Gilded Age, but for a few people, it was a massive bonanza. California’s Leland Stanford was one of the robber barons who profited from this. Stanford had few meaningful politics to speak of: He was anti-slavery inasmuch as he believed that the country’s “greatest good had been derived by having all of the country settled by free white men.” In 1861, Stanford ran for governor again and won on the strength of the Democrats being divided and too closely associated with the Confederacy. Even his own white supremacy was conditional: In his inaugural speech, he railed against Chinese immigration. Within a few years, he would employ thousands of them.

Stanford’s real political goal was a railroad. When an engineer named Theodore Judah tried to pitch a route in San Francisco, the city’s financiers refused to back it precisely because it wouldn’t be profitable. Between California and Nebraska, there was virtually nothing to justify having a railroad. But Stanford and his associates’ planned to get the state and federal government to pay for it—and get rich themselves. They formed a new business, the Central Pacific Railroad, and made Leland Stanford the president of it. What they got was the Pacific Railroad Act. First, they received bonds from the government that they could then sell for cash. They also got land grants for the territories through which they built. By the 1870s, railroad companies had received more than 175 million acres of land, more than the state of Texas.

Stanford and his associates (which is how they referred to themselves) stole as much as they could: To build the railroad, they formed a construction company they owned entirely that would “sell” materials back to the railroad at a tidy profit. Stanford treated the Central Pacific like a bank account, taking from it what he wanted. When eventually questioned about this by Congress decades later, Stanford claimed that the books had been lost, pleaded the Fifth, and got away with it.

Today, we can expect that Trump’s allies will treat the federal government like a piggy bank to fund projects they otherwise couldn’t get away with. Musk’s tunnels in Las Vegas, for example, have so far gotten away with no oversight because it has no federal funding. But now that he’s got a friendly administration to work with and is heading up a public relations exercise, the Department of Governmental Efficiency (DOGE), it appears he can at least try to get more funding while also tearing down regulations that would constrain the Boring Company, Musk’s tunnel construction company. The tunnels won’t alleviate traffic or substitute for a mass transit system, as experts have argued, but that’s irrelevant. One can imagine the Department of Transportation rolling grant funding to the Boring Company to build these tunnels across the country. Much the same as the transcontinental railroad, the money is in building it, and we pay the bill.

Financial Panics

When you’re so wealthy that it stops mattering, everything becomes a game—and the Gilded Age robber barons played games. Jay Gould was among the most infamous in part because he meddled where he could simply to prove how powerful he was. Gould cozied up to President Ulysses S. Grant’s brother-in-law, Abel Corbin, to try to corner the gold market. They hoped to do this by using the relationship with Grant to persuade the government to stop releasing gold from the treasury, which would raise the price of gold while they hoarded what was available. It ultimately failed. Grant and the Treasury Department eventually released gold, but the ensuing economic chaos led to a financial panic in 1869. Even though he lost money from the attempt, Gould escaped any responsibility, shielded by judges who were politically connected to him in New York. It was a pointless and destructive game by a man who was already fantastically wealthy.

The Gilded Age was an era full of financial panics. Gould engineering a panic just to see if he could seize control of the country’s gold supply was just one example. The Panic of 1873 drove a quarter of all railroads into bankruptcy, a recession lingered through the 1880s, and another severe panic in 1893 brought unemployment close to 15%. The specific causes could be complex, but the underlying roots were simple: Banks and individuals were allowed to make investments that were too risky and operated fraudulently. When they collapsed, they took down everything else with them. Individuals had no protection in any of this: If your bank failed, you lost any savings you had there. Politicians and even bankers in the 20th century wanted to end the cycle of devastating depressions, which is why we have so many financial regulations today.

The Trump administration wants to roll back as many regulations as they can—they’ll try and take as close to the Gilded Age as they can. Vivek Ramaswamy (who has since withdrawn from DOGE) already floated the idea of ending the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which protects and insures your savings if your bank fails. Extreme? Perhaps. But Trump’s new Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent (himself a wealthy hedge-fund manager) is in favor of deregulating energy markets and the financial sector. Paul Atkins, Trump’s pick for the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), previously worked there and went out of his way to avoid punishing companies for their behavior. We’re going to see banks and investors given carte blanche to do what they want, regardless of the damage they cause.

State Capture

For a brief moment following the Civil War, Southern governments did something extraordinary: They tried to expand the services they offered to their citizens. This faced violent opposition from ex-Confederates and spurred the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, but between 1865 and 1877 public schooling became a reality for the first time in the South. To jumpstart economic growth, states supported railroads, such as the Western & Atlantic in Georgia. It had been built prior to the Civil War and was state-owned—until Confederates came back into power. The railroad was losing money, and it was transferred to a private company in 1871, whose president, Joseph Brown, was a former governor of the state and became its senator from 1880 to 1890.

Brown effectively controlled the state of Georgia in a political alliance with two other men, Alfred Colquitt and John Brown Gordon. These men were known as “redeemers,” because they ended Reconstruction and worked to re-enshrine white supremacy. They complained about the corruption of Reconstruction governments and promised to clean it up. They weren’t your typical robber barons: their money originally lay in cotton and the plantation system, and their wealth wasn’t on par with Carnegie, Stanford, or Rockefeller. But they used their connections to build business empires and steal what they could. Brown controlled the Western & Atlantic Railroad, the Dade Coal Company, and a host of iron smelting companies. He got workers from the state’s convict leasing system, which effectively reinstituted slavery by criminalizing things like vagrancy: once arrested, people could be leased out as workers on contracts.

This is one goal that Musk and others have for the U.S. government today. They even say many of the same things about corruption and promising to get rid of it. They want to carve off parts of the federal government and either privatize their functions and seize them for themselves, or simply destroy them. Musk’s claims of efficiency or his plans to have the contracts reviewed by AI are really just good for one thing: finding ways to reroute them to Trump allies or himself. It has little to do even with the “deep state.” It’s a simple vehicle for graft, and patronage.

Cronyism

The Gilded Age was an era of political cronyism. Governmental offices were given out as rewards for political supporters. Competence was less important than loyalty, and offering jobs was part of the payback any president had to do in order to get elected. Obviously, it makes for a less efficient government because of the high rates of turnover.

Worse, cronyism greased the wheels of corruption. It even helped to create new robber barons. At the beginning of the 20th century, Charles Herbert Allen was appointed the first civilian governor of Puerto Rico, which had recently been ceded to the United States following the Spanish-American War. Allen was only in office for 15 months but used his time to seed the island with political appointees. When he resigned, he founded a sugar syndicate, the American Sugar Refining Company, that within a few decades controlled most of the island’s sugar production as well as the island’s railroad and seaport. His various cronies who stayed in power after he left ensured that his company got subsidies and land grants. Today, the company he founded is Domino Sugar.

Trump has made no secret of the fact that he wants to use the civil service as a political tool. In his first term, he signed an executive order to reclassify a number of federal employees as Schedule F, meaning that they are at-will employees and can thus be summarily dismissed and replaced. This was reversed under Biden, but now Trump is back in office and there’s a very real fear that he’ll use this to silence federal employees who dare to disagree with him. That movement in and out of government creates an opening for people who want to use it for their own ends, like Charles Herbert Allen.

Assaults on Labor

Robber barons did not have a friendly relationship with organized labor. Andrew Carnegie, who has been idolized since his death because of his charitable giving, nevertheless relied on his partner Henry Clay Frick to violently shut down labor organizing at his steel mills. Robber barons could hire small armies of strikebreaking private detectives, the most infamous of them being Pinkertons. Jay Gould’s claim that “I can pay half of the working class to kill the other half” is horrifying on its own, but even when Pinkertons and local police weren’t enough, the ensuing fighting could bring in the government. Federal troops were always there as the ultimate backstop to shut down striking workers, especially in moments of major unrest such as the Strike of 1877 or the Pullman Strike in 1894.

But even outside of the threat of force, the federal government targeted labor when and where it could. The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890 to regulate monopolies was first turned on labor unions in 1894 during the Pullman Strike. A federal judge issued an injunction to stop striking workers from boycotting Pullman cars and blocking U.S. mail from being sent. Their justification? The Sherman Antitrust Act, on the basis that the union was restricting trade and commerce. In re Debs upheld the legality of judges issuing injunctions to order strikes to end.

At the moment, Trump looks like he’s trying to paint himself as a moderate on labor. He won the endorsement of the Teamsters in the election, and his pick for Secretary of Labor, Lori Chavez-DeRemer, is seen as a moderate on labor issues. But if you look beyond Chavez-DeRemer, the Trump administration is aggressively anti-labor. Project 2025 spelled out a wishlist of giveaways, including waivers to states that will let them bypass overtime or minimum-wage requirements. Other goals include banning public sector unions such as AFSCME and legalizing strikebreaking tactics such as retaliating against union organizers. Members of the Trump administration have discussed ways of “disabling” the National Labor Relations Board, which would make enforcing federal labor law very difficult.

If these changes go through, the effect on labor will be chilling—but also radicalizing. Union organizers in the 19th century fought so militantly precisely because they had few legal options open to them. If we strip away those legal protections and their seat at the table, workers will push back.

The Corrosive Effect on Politics

In the Gilded Age, Congress was the butt of a thousand jokes. Mark Twain wrote, “It could probably be shown by facts and figures that there is no distinctly native American criminal class except Congress.” Political cartoons depicted Congress as either weak or corrupt and presidents were generally dismissed as forgettable. A good deal of that was simply because Congress has become so compromised by big business and robber barons.

By the 1880s, political office was a kind of ornament for some of these robber barons to wear. Leland Stanford ran for the Senate in 1885 and won with the public widely believing that he had bribed the legislature (all senators were elected by state legislatures until 1913). He didn’t do much while in office; he often missed votes to pay attention to his race horses. George Hearst, a mining magnate, was appointed to the Senate by California’s legislature in 1887 to fill an absence. William A. Clark was a mining magnate from Montana who first bribed the state legislature to make him a senator in 1899. When the Senate refused to seat him, he simply did it again in 1901 and got his seat.

Even senators and representatives who weren’t themselves robber barons got sucked into the abyss of money. To try and build the Northern Pacific Railroad, Jay Cooke needed access to Native American land in Minnesota. In an attempt to win access, he appointed William Wisdom, one of Minnesota’s senators, to the board of the Northern Pacific Railroad. At almost the same time, a scandal emerged: The Credit Mobilier, a construction company for the Union Pacific railroad, was found to have sold stock at a discount to congressmen. The head of the Credit Mobilier was Oakes Ames, a congressman, and when this was discovered, his defense was that selling the stock at a discount didn’t make it a bribe. Ames was censured, but didn’t lose his seat, nor were the money from the bribes ever recovered, despite the fact that the money belonged to the public.

This is perhaps one of the most insidious consequences of Gilded Age politics and what we might see today: hopelessness. Corrupt act after corrupt act lulls people into not caring. Even as people turn out to vote, there’s a passive acceptance that government won’t do very much and that it can’t work on our behalf. In conjunction with an administration that will tolerate voter suppression and gerrymandering, the effect is going to be really toxic for democracy.

Elon Musk’s intrusion into the Treasury is, in a word, unprecedented. It’s hard to find something comparable to it during the Gilded Age. But consider a cartoon like Bosses of the Senate, which says that the true power behind government is wealth. And that’s exactly the message that is being sent right now. Musk is trampling over the law simply because he’s wealthy enough and closely aligned enough to Trump to do so. People are still speculating as to his ultimate goal, whether it’s using AI to review contracts and then reroute them to his businesses, or turning them over to Trump to use as a political cudgel. For us however, the experience is the same: We’re out of power.